By John Treadwell Dunbar ——Bio and Archives--February 28, 2011

Travel | CFP Comments | Reader Friendly | Subscribe | Email Us

When 16th century Spanish conquistador García López de Cárdenas stepped out of the towering ponderosa pines that blanket the South Rim of the grandest of canyons and stared dumfounded at that reddish convoluted maw, stared in disbelief at the depth and width and breadth of that crinkly crack, he most assuredly was moved with a profound sense of humility like counted millions since his day that have paid homage from the corners of planet earth.

Like many in contemporary society, Cardenas struggled for words to describe this geologic anomaly, this thing, this increasingly polluted void carved out of the Colorado Plateau over the course of eons that has brought man to the brink of tears with its incomprehensible beauty.

When 16th century Spanish conquistador García López de Cárdenas stepped out of the towering ponderosa pines that blanket the South Rim of the grandest of canyons and stared dumfounded at that reddish convoluted maw, stared in disbelief at the depth and width and breadth of that crinkly crack, he most assuredly was moved with a profound sense of humility like counted millions since his day that have paid homage from the corners of planet earth.

Like many in contemporary society, Cardenas struggled for words to describe this geologic anomaly, this thing, this increasingly polluted void carved out of the Colorado Plateau over the course of eons that has brought man to the brink of tears with its incomprehensible beauty.

DEEP: Cut by the steep gradient of an unchecked Colorado River and scoured by summer monsoons, the Grand Canyon is not your average pothole. It plunges over a mile from the North Rim (8,200') down to the muddy river. Depending on your expert, the river, averaging 300' in width, took 17 million years to carve out multihued layers of red, black and white, crimson and tan; a shifting palette burnished onto vast mesas, sheer cliffs, eroding benches and sprawling tables. Interspersed with spires and sandstone blocks as daunting as cathedrals, the canyon's walls are a vivacious schematic, a wasting canvas exposing 1.7 billion years of geologic history.

The drastic drop in elevation means a hike into the bowels of the gorge will take you through numerous ecosystems; five life zones and three desert types known in North America. In one day you're traveling from Canada to Mexico, from alpine forests of ponderosa and aspens to the scorching heat of Lower Sonoran Desert. All this in the span of a few hours if you hoof it, and much faster if you take that extra step in the wrong direction and plummet a thousand feet like a bread crumb swept off the kitchen table.

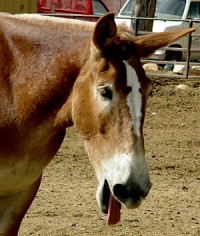

Those tender of foot might consider hiring the services of a rabbit-eared mule. South Rim mule trips are popular, especially the overnight excursions to the river which may range from $480 to $850 for one or two guests. But for half that price I'll gladly carry you down myself, tuck you in and roll you back to the top in a wheelbarrow the next day.

DEEP: Cut by the steep gradient of an unchecked Colorado River and scoured by summer monsoons, the Grand Canyon is not your average pothole. It plunges over a mile from the North Rim (8,200') down to the muddy river. Depending on your expert, the river, averaging 300' in width, took 17 million years to carve out multihued layers of red, black and white, crimson and tan; a shifting palette burnished onto vast mesas, sheer cliffs, eroding benches and sprawling tables. Interspersed with spires and sandstone blocks as daunting as cathedrals, the canyon's walls are a vivacious schematic, a wasting canvas exposing 1.7 billion years of geologic history.

The drastic drop in elevation means a hike into the bowels of the gorge will take you through numerous ecosystems; five life zones and three desert types known in North America. In one day you're traveling from Canada to Mexico, from alpine forests of ponderosa and aspens to the scorching heat of Lower Sonoran Desert. All this in the span of a few hours if you hoof it, and much faster if you take that extra step in the wrong direction and plummet a thousand feet like a bread crumb swept off the kitchen table.

Those tender of foot might consider hiring the services of a rabbit-eared mule. South Rim mule trips are popular, especially the overnight excursions to the river which may range from $480 to $850 for one or two guests. But for half that price I'll gladly carry you down myself, tuck you in and roll you back to the top in a wheelbarrow the next day.

WIDE: At its widest the Grand Canyon spans 18 miles, and a rim-to-rim hike is roughly 22 miles long. This well-trod corridor is called the "Corridor" and it is advised that those embarking from the south headed north descend along waterless South Kaibab Trail (6.3 miles), camp, and then climb out via the North Kaibab Trail (14.2 miles).

You should not attempt a rim-to-rim hike in one day, particularly during the brutally hot summer months. And hiking down from the South Rim to the river and back in one day is likewise discouraged. The southern trails are crowded, the North Rim regions less so. And remember, should you not feel like completing a rim-to-rim-to-rim hike, you've got a 220-mile drive to contend with, a 5 1/2-hour return trip which can become a logistical inconvenience at best. Contact Grand Canyon Coaches or the Trans-Canyon Shuttle if you lack that extra car and are short on time.

Some throw reason to the wind and squeeze a rim-to-rim hike in to one long day, like my uncle sixty years ago. The tall, gangly absent-minded mathematician set out to cross the abyss in city shoes, with little water and a few cans of food only to discover he forgot his can opener, didn't enjoy desert hiking in the least and became crippled with a rash of blisters. But he crossed "The Big One" during the heat of summer and lived to complain about it.

WIDE: At its widest the Grand Canyon spans 18 miles, and a rim-to-rim hike is roughly 22 miles long. This well-trod corridor is called the "Corridor" and it is advised that those embarking from the south headed north descend along waterless South Kaibab Trail (6.3 miles), camp, and then climb out via the North Kaibab Trail (14.2 miles).

You should not attempt a rim-to-rim hike in one day, particularly during the brutally hot summer months. And hiking down from the South Rim to the river and back in one day is likewise discouraged. The southern trails are crowded, the North Rim regions less so. And remember, should you not feel like completing a rim-to-rim-to-rim hike, you've got a 220-mile drive to contend with, a 5 1/2-hour return trip which can become a logistical inconvenience at best. Contact Grand Canyon Coaches or the Trans-Canyon Shuttle if you lack that extra car and are short on time.

Some throw reason to the wind and squeeze a rim-to-rim hike in to one long day, like my uncle sixty years ago. The tall, gangly absent-minded mathematician set out to cross the abyss in city shoes, with little water and a few cans of food only to discover he forgot his can opener, didn't enjoy desert hiking in the least and became crippled with a rash of blisters. But he crossed "The Big One" during the heat of summer and lived to complain about it.

Others aren't as fortunate as statistics bear out. Roughly 250 rescues are performed yearly. Heat stroke is a contributor. Dehydration kills, femurs snap, the unprepared become lost, they drown in raging currents of the Colorado, they trip and fall, they suffer heart attacks, stroke. There's snakes, there's scorpions. Lightning bolts streak out of beautiful black skies and roast the unexpected standing stupidly on exposed canyon rims. The same black skies disgorge drenching rains with a flash and a boom that dislodge boulders and send them tumbling and push muddy streams down narrow canyons, roaring, cascading gracefully over sheer cliffs; walls of dirty water that sweep the ignorant into rocky gullies for a painful pummeling that never ends good.

LONG: At 277 miles, the Grand Canyon is longer than some states. There are only two ways to travel the canyon below the rim from end to end that I know of. Difficult to imagine, but the hardy and truly driven have walked its tortured length on foot. Colin Fletcher (1922 - 2007) is probably the most renowned and was regarded by many as a spiritual godfather to legions of backpackers. A venerated environmentalist, Mr. Fletcher penned, among other noteworthy books, a memoir of his Grand Canyon exploits, "The Man Who Walked Through Time." Wonderful read, a real classic.

The more popular and costly route is by water, down the mighty and frequently muddy Colorado River, putting in at Lees Ferry and taking out at Diamond Creek. Trip lengths vary. Seven days is usually the minimum if you travel in one of those enormous motorized rubber rafts, but you have the option of shortening the trip and saving a few dollars if you hike out at Phantom Ranch. Short floats (3 days) will give you a taste of the canyon, but if you seek a life-altering experience, a transcendental nirvanic state of watery bliss, think about an 18-day commercial trip, or 25-day oared or paddled noncommercial drift with friends and acquaintances. Some prefer a dory, and many take along their whitewater kayaks for grins and independence.

Others aren't as fortunate as statistics bear out. Roughly 250 rescues are performed yearly. Heat stroke is a contributor. Dehydration kills, femurs snap, the unprepared become lost, they drown in raging currents of the Colorado, they trip and fall, they suffer heart attacks, stroke. There's snakes, there's scorpions. Lightning bolts streak out of beautiful black skies and roast the unexpected standing stupidly on exposed canyon rims. The same black skies disgorge drenching rains with a flash and a boom that dislodge boulders and send them tumbling and push muddy streams down narrow canyons, roaring, cascading gracefully over sheer cliffs; walls of dirty water that sweep the ignorant into rocky gullies for a painful pummeling that never ends good.

LONG: At 277 miles, the Grand Canyon is longer than some states. There are only two ways to travel the canyon below the rim from end to end that I know of. Difficult to imagine, but the hardy and truly driven have walked its tortured length on foot. Colin Fletcher (1922 - 2007) is probably the most renowned and was regarded by many as a spiritual godfather to legions of backpackers. A venerated environmentalist, Mr. Fletcher penned, among other noteworthy books, a memoir of his Grand Canyon exploits, "The Man Who Walked Through Time." Wonderful read, a real classic.

The more popular and costly route is by water, down the mighty and frequently muddy Colorado River, putting in at Lees Ferry and taking out at Diamond Creek. Trip lengths vary. Seven days is usually the minimum if you travel in one of those enormous motorized rubber rafts, but you have the option of shortening the trip and saving a few dollars if you hike out at Phantom Ranch. Short floats (3 days) will give you a taste of the canyon, but if you seek a life-altering experience, a transcendental nirvanic state of watery bliss, think about an 18-day commercial trip, or 25-day oared or paddled noncommercial drift with friends and acquaintances. Some prefer a dory, and many take along their whitewater kayaks for grins and independence.

As you lounge in the sand on a balmy evening beside the rolling river replaying the thrill of whitewater descents and celestial red rock scenery in your relaxing mind, as you gorge on T-bone steaks and lobster and get liquored-up on Quervo and Heinekens and pass the peace pipe counterclockwise and watch the hired help do all the heavy lifting, remember those who came before you, and respect them for their selfless daring-do and reckless abandon that paved the way for lazy lizards like you and me.

Long before rubber boats and life preservers, topo maps and satellite phones, rescue helicopters and diesel engines and the iPod, brave men in scraggly beards plunged through the Grand Canyon in wood dingies without today's life vests, listening intently to the river's roar cascade off narrow canyon walls without a clue as to what lay around the bend but expecting the absolute worst.

Major John Wesley Powell comes foremost to mind. The one-armed soldier, ethnologist, geologist and explorer extraordinaire lead nine men in four boats on a harrowing float down the Green and Colorado, becoming the first European Americans to traverse the length of the Grand Canyon in 1869. He did it again in 1870-71.

As you lounge in the sand on a balmy evening beside the rolling river replaying the thrill of whitewater descents and celestial red rock scenery in your relaxing mind, as you gorge on T-bone steaks and lobster and get liquored-up on Quervo and Heinekens and pass the peace pipe counterclockwise and watch the hired help do all the heavy lifting, remember those who came before you, and respect them for their selfless daring-do and reckless abandon that paved the way for lazy lizards like you and me.

Long before rubber boats and life preservers, topo maps and satellite phones, rescue helicopters and diesel engines and the iPod, brave men in scraggly beards plunged through the Grand Canyon in wood dingies without today's life vests, listening intently to the river's roar cascade off narrow canyon walls without a clue as to what lay around the bend but expecting the absolute worst.

Major John Wesley Powell comes foremost to mind. The one-armed soldier, ethnologist, geologist and explorer extraordinaire lead nine men in four boats on a harrowing float down the Green and Colorado, becoming the first European Americans to traverse the length of the Grand Canyon in 1869. He did it again in 1870-71.

That's right, one arm, wood boats, an endless barrage of whitewater rapids of stupendous velocity and immense volume; big drops like greatly-feared and awe-inspiring Lava Falls at mile 179.2, scary stuff by any measure today, and even scarier by a long shot in the 19th century. You can read about their stunning conquest in "Beyond the Hundredth Meridian: John Wesley Powell and the Second Opening of the West" by one of America's finest authors, Wallace Stegner. Great read.

CROWDED: There's no sugarcoating this thing. The 1.2 million acre national park receives five million visitors a year, leaving many to wonder why they bother calling the Grand Canyon Village a village. Fortunately, most hang out on the South Rim and many are content to briefly peek over the side at convenient pullouts and snap a few for posterity. Nevertheless, the crowds at the South Rim can be depressing although shuttle buses are easing the pain and thinning out the masses, particularly near some of the viewpoints. The Grand Canyon Railway between Williams and the village helps ease traffic congestion considerably.

The obscene nature of these crowds manifests itself most near lodging facilities. The iconic Bright Angel, Thunderbird, Katchina and El Tovar lodges might be popular, but perched so close to the canyon's rim they form a narrow corridor crawling with human ants. I've never seen anything quite like it. Shoulder to shoulder, cheek to cheek, it looks like a Manhattan sidewalk during lunch.

That's right, one arm, wood boats, an endless barrage of whitewater rapids of stupendous velocity and immense volume; big drops like greatly-feared and awe-inspiring Lava Falls at mile 179.2, scary stuff by any measure today, and even scarier by a long shot in the 19th century. You can read about their stunning conquest in "Beyond the Hundredth Meridian: John Wesley Powell and the Second Opening of the West" by one of America's finest authors, Wallace Stegner. Great read.

CROWDED: There's no sugarcoating this thing. The 1.2 million acre national park receives five million visitors a year, leaving many to wonder why they bother calling the Grand Canyon Village a village. Fortunately, most hang out on the South Rim and many are content to briefly peek over the side at convenient pullouts and snap a few for posterity. Nevertheless, the crowds at the South Rim can be depressing although shuttle buses are easing the pain and thinning out the masses, particularly near some of the viewpoints. The Grand Canyon Railway between Williams and the village helps ease traffic congestion considerably.

The obscene nature of these crowds manifests itself most near lodging facilities. The iconic Bright Angel, Thunderbird, Katchina and El Tovar lodges might be popular, but perched so close to the canyon's rim they form a narrow corridor crawling with human ants. I've never seen anything quite like it. Shoulder to shoulder, cheek to cheek, it looks like a Manhattan sidewalk during lunch.

It's a good thing the park maintains 15 trails and several obscure routes throughout the canyon for overnight camping and a measure of solitude. Unfortunately 30,000 requests for backcountry permits are received, 13,000 permits issued and nearly 40,000 individuals camp overnight.

Naturally, rules and regulations follow. Here are two that may come in handy. If you're down by the river and need to take a leak, you must do so in the wet sand near the water's edge, I'm not sure why. Ladies, on behalf of the National Park Service and all those who look the other way, and those who don't, I apologize. As for used toilet paper, failure to wad it up, stuff it in your shirt pocket and haul it out of the canyon is now a class A felony that will net you 15-to-life at Leavenworth. On second thought, with 40,000 rampant squatters it's probably a good idea, especially on extra-windy days that would otherwise turn the blue sky into a deadly clutter of brown confetti.

Things aren't much better along the river. Strong demand, limited supply and a regressive permit system meant that prior to 2006 the waiting list for noncommercial permits for the long trips grew to 25 years (What? Say what?). After 2006 the waiting list system was converted to a weighted lottery program which evidently helps, somewhat. And for anyone wishing to float the river more than once a year, commercial or noncommercial, forget about it.

It's a good thing the park maintains 15 trails and several obscure routes throughout the canyon for overnight camping and a measure of solitude. Unfortunately 30,000 requests for backcountry permits are received, 13,000 permits issued and nearly 40,000 individuals camp overnight.

Naturally, rules and regulations follow. Here are two that may come in handy. If you're down by the river and need to take a leak, you must do so in the wet sand near the water's edge, I'm not sure why. Ladies, on behalf of the National Park Service and all those who look the other way, and those who don't, I apologize. As for used toilet paper, failure to wad it up, stuff it in your shirt pocket and haul it out of the canyon is now a class A felony that will net you 15-to-life at Leavenworth. On second thought, with 40,000 rampant squatters it's probably a good idea, especially on extra-windy days that would otherwise turn the blue sky into a deadly clutter of brown confetti.

Things aren't much better along the river. Strong demand, limited supply and a regressive permit system meant that prior to 2006 the waiting list for noncommercial permits for the long trips grew to 25 years (What? Say what?). After 2006 the waiting list system was converted to a weighted lottery program which evidently helps, somewhat. And for anyone wishing to float the river more than once a year, commercial or noncommercial, forget about it.

PRETTY: I didn't believe them when they said the Grand Canyon is too beautiful for words, that transposing the divine to human gibberish simply cannot be done. Not one to back down easily, I threw down the gauntlet one afternoon while standing on the South Rim near Yaki Point, staring out at the vast indescribable before me. I'm a wordsmith, after all, a scribbler, a fair phraseologist, a medium for the masses, a meager thinker of mind-numbing minutia.

Gathered around me was a small crowd of onlookers, Germans and the Dutch, a family of New Yorkers and the French. Mustering my mental proclivities and searching the clammy recesses of my conflicted mind for just the right words, the perfect turn of phrase, I took a deep breath and sputtered, “Umpth grppble punrqas ptomticm.”

The crowd stepped back. I tried again, “razmtazmglerbop.” And then I panicked and dropped to one knee, arms out, doing an Al Jolsen.

“Rasm morto plopptcm! Asswip toslobsweek?”

I slathered, spewing consonants, vowels and dangling participles all over my shirt, down my collar, here an adjective, there a noun. I cried like a girl, begged my muse for a little help, anything, please. Tears streamed down my jowls.

“Flingiubu **#@$%” I hollered. “You mother-*&^53%$ ….” and on it went until I finally ceded in utter frustration, just gave up, tipping my hat to them, all of them, each and every one because they are absolutely right. The Grand Canyon is simply too beautiful for words. So I picked myself up out of the dirt, wiped the spit out of my beard and went back to taking pictures.

PRETTY: I didn't believe them when they said the Grand Canyon is too beautiful for words, that transposing the divine to human gibberish simply cannot be done. Not one to back down easily, I threw down the gauntlet one afternoon while standing on the South Rim near Yaki Point, staring out at the vast indescribable before me. I'm a wordsmith, after all, a scribbler, a fair phraseologist, a medium for the masses, a meager thinker of mind-numbing minutia.

Gathered around me was a small crowd of onlookers, Germans and the Dutch, a family of New Yorkers and the French. Mustering my mental proclivities and searching the clammy recesses of my conflicted mind for just the right words, the perfect turn of phrase, I took a deep breath and sputtered, “Umpth grppble punrqas ptomticm.”

The crowd stepped back. I tried again, “razmtazmglerbop.” And then I panicked and dropped to one knee, arms out, doing an Al Jolsen.

“Rasm morto plopptcm! Asswip toslobsweek?”

I slathered, spewing consonants, vowels and dangling participles all over my shirt, down my collar, here an adjective, there a noun. I cried like a girl, begged my muse for a little help, anything, please. Tears streamed down my jowls.

“Flingiubu **#@$%” I hollered. “You mother-*&^53%$ ….” and on it went until I finally ceded in utter frustration, just gave up, tipping my hat to them, all of them, each and every one because they are absolutely right. The Grand Canyon is simply too beautiful for words. So I picked myself up out of the dirt, wiped the spit out of my beard and went back to taking pictures.View Comments

John Treadwell Dunbar is a freelance writer