By John Treadwell Dunbar ——Bio and Archives--March 2, 2012

Travel | CFP Comments | Reader Friendly | Subscribe | Email Us

This was a rut I was grateful to be stuck in one crisp, blue-sky morning in eastern Wyoming. Standing deep in a trough on a sparsely wooded hill overlooking the North Platte River near the outskirts of Guernsey, I felt the earth rumble as oxen mooed, whips cracked, and covered wagons creaked up the steep rutted incline hauling heavy loads of the essentials, and the trivial. Hardened women in bonnets and long skirts followed coughing in the dust, and men in hats on horses yelled at their livestock and encouraged children and the old staggering to keep pace.

Among this rolling wave of humanity were hundreds of poor English and Scandinavian Mormons on foot who had no idea what awaited them in October of 1856 as they pushed and pulled two-wheeled carts with bloody hands ever-onward to Zion and the Valley of the Salt Lake for 1,300 tiresome miles in the ultimate test of their faith.

This was a rut I was grateful to be stuck in one crisp, blue-sky morning in eastern Wyoming. Standing deep in a trough on a sparsely wooded hill overlooking the North Platte River near the outskirts of Guernsey, I felt the earth rumble as oxen mooed, whips cracked, and covered wagons creaked up the steep rutted incline hauling heavy loads of the essentials, and the trivial. Hardened women in bonnets and long skirts followed coughing in the dust, and men in hats on horses yelled at their livestock and encouraged children and the old staggering to keep pace.

Among this rolling wave of humanity were hundreds of poor English and Scandinavian Mormons on foot who had no idea what awaited them in October of 1856 as they pushed and pulled two-wheeled carts with bloody hands ever-onward to Zion and the Valley of the Salt Lake for 1,300 tiresome miles in the ultimate test of their faith. To the dismay of people outside the faith, Mormonism expanded rapidly and its members prospered, becoming highly organized and disciplined. They assembled a large and well-armed militia and appeared to challenge the religious and political status quo of local communities. Whereas in the United States great measures are taken to separate church and state, in the Mormon world the two institutions seemed to merge into an independent, self-contained theocracy. And to add fuel to the fire, their practice of polygamy was anathema to mainstream Christians.

To the dismay of people outside the faith, Mormonism expanded rapidly and its members prospered, becoming highly organized and disciplined. They assembled a large and well-armed militia and appeared to challenge the religious and political status quo of local communities. Whereas in the United States great measures are taken to separate church and state, in the Mormon world the two institutions seemed to merge into an independent, self-contained theocracy. And to add fuel to the fire, their practice of polygamy was anathema to mainstream Christians.

The Missouri state militia and vigilante mobs set about running all Mormons out of the state, or exterminating them under color of law. Outright war against Mormons and their bloody persecution reached its zenith in the execution-style shooting of church founder and prophet Joseph Smith and his brother Hyrum by an Illinois mob in 1844. By 1845 rabid Mormon-haters determined to purge the land of the "infidels" burned over 200 homes and farms in and around Nauvoo, Illinois, which boasted a Mormon population of 11,000. That was the last straw. Finalizing earlier plans to emigrate west to a more forgiving promised land, and fearing an attack on the city by federal troops, the first party of settlers left Nauvoo in February, 1846, under the guidance of their new leader, Brigham Young.

After crossing Nebraska, the Mormon Trail merged with the Oregon and California Trail at Fort Laramie, now a wonderfully restored national park not far from Guernsey. In 1841 Fort John, which became Fort Laramie, was no more than a small adobe trading post swarming with the adventurous, trappers, and Plains Indians who routinely pitched teepees in the vicinity. By 1849 the fort began to evolve into a large and crucial military outpost and community where all manner of passing emigrants worn down by the sheer drudgery of trail life replenished supplies and restored spirits, some liquid, before continuing down the increasingly difficult trail.

The Missouri state militia and vigilante mobs set about running all Mormons out of the state, or exterminating them under color of law. Outright war against Mormons and their bloody persecution reached its zenith in the execution-style shooting of church founder and prophet Joseph Smith and his brother Hyrum by an Illinois mob in 1844. By 1845 rabid Mormon-haters determined to purge the land of the "infidels" burned over 200 homes and farms in and around Nauvoo, Illinois, which boasted a Mormon population of 11,000. That was the last straw. Finalizing earlier plans to emigrate west to a more forgiving promised land, and fearing an attack on the city by federal troops, the first party of settlers left Nauvoo in February, 1846, under the guidance of their new leader, Brigham Young.

After crossing Nebraska, the Mormon Trail merged with the Oregon and California Trail at Fort Laramie, now a wonderfully restored national park not far from Guernsey. In 1841 Fort John, which became Fort Laramie, was no more than a small adobe trading post swarming with the adventurous, trappers, and Plains Indians who routinely pitched teepees in the vicinity. By 1849 the fort began to evolve into a large and crucial military outpost and community where all manner of passing emigrants worn down by the sheer drudgery of trail life replenished supplies and restored spirits, some liquid, before continuing down the increasingly difficult trail.

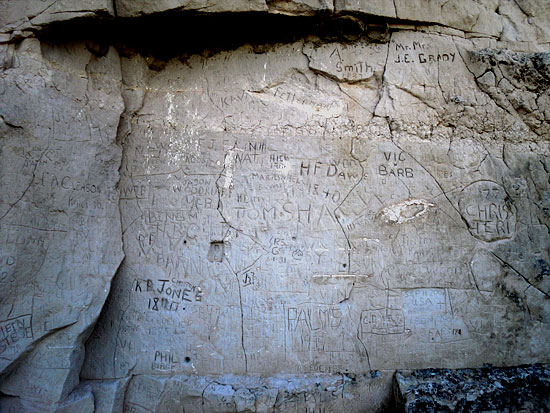

Thousands carved their names into the long sandstone bluffs at Register Cliffs, the other historic attraction near tiny Guernsey. It's park-like and pleasant with meandering turns of the occasionally bloated North Platte in view. During our morning sojourn the only other visitors we stumbled across were tame rabbits hopping beneath our car and across green lawns at the foot of crumbling walls awash in hundreds of antiquated scripts still visible, and a few too many contemporary etchings by the Saturday late-night crowd.

We picked up the trail near Casper (Pop. 30,000) and toured the 15,000-square-foot National Historic Trails Interpretive Center. The multimillion dollar cavernous complex overlooks the city and offers seven state-of-the-art exhibits, audio and visual presentations, simulated wagon rides across the North Platte, and Native American storytelling stations. The center commemorates in exquisite detail the Oregon-California-Mormon Trail experience, and more. It gives us the story, come to life, of the traveling emigrants' westward adventures and even pays tribute to Native Americans who called the territory home.

Thousands carved their names into the long sandstone bluffs at Register Cliffs, the other historic attraction near tiny Guernsey. It's park-like and pleasant with meandering turns of the occasionally bloated North Platte in view. During our morning sojourn the only other visitors we stumbled across were tame rabbits hopping beneath our car and across green lawns at the foot of crumbling walls awash in hundreds of antiquated scripts still visible, and a few too many contemporary etchings by the Saturday late-night crowd.

We picked up the trail near Casper (Pop. 30,000) and toured the 15,000-square-foot National Historic Trails Interpretive Center. The multimillion dollar cavernous complex overlooks the city and offers seven state-of-the-art exhibits, audio and visual presentations, simulated wagon rides across the North Platte, and Native American storytelling stations. The center commemorates in exquisite detail the Oregon-California-Mormon Trail experience, and more. It gives us the story, come to life, of the traveling emigrants' westward adventures and even pays tribute to Native Americans who called the territory home.

Confrontations between whites and Indians weren't as frequent as Hollywood would have us believe, but they did happen. Four miles west of Casper off Highway 220 we stopped in the shadow of a low red mountain near the Battle of Red Buttes where on July 26, 1865, Arapaho, Cheyenne, and Sioux Indians attacked three military wagons north of the river. The white man lost this one. A plaque commemorates the bloody shootout which lasted four hours and took the lives of 22 U.S. soldiers.

While such attacks were no doubt on emigrants' minds, it was not the dominant threat during those 30 years as only 350 people were killed at the hands of Indians who looked on helplessly as their lands were overrun by that seething westward flow of humanity. Cholera slew the largest percentage of the unfortunate 39,000 who are buried along the trail in marked and unmarked shallow graves now long forgotten.

Confrontations between whites and Indians weren't as frequent as Hollywood would have us believe, but they did happen. Four miles west of Casper off Highway 220 we stopped in the shadow of a low red mountain near the Battle of Red Buttes where on July 26, 1865, Arapaho, Cheyenne, and Sioux Indians attacked three military wagons north of the river. The white man lost this one. A plaque commemorates the bloody shootout which lasted four hours and took the lives of 22 U.S. soldiers.

While such attacks were no doubt on emigrants' minds, it was not the dominant threat during those 30 years as only 350 people were killed at the hands of Indians who looked on helplessly as their lands were overrun by that seething westward flow of humanity. Cholera slew the largest percentage of the unfortunate 39,000 who are buried along the trail in marked and unmarked shallow graves now long forgotten.

Lack of water and grass feed also plagued them during extended dry spells. Where water became available it sometimes was alkaline-poisoned. Despite written warnings posted near such water sources, some emigrants were illiterate and paid the ultimate price for their thirst and ignorance with a wretched, painful ending. Death and sickness were also transmitted, most likely, by ticks which infected the unknowing with Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever, particularly on that gradual 100-mile incline between Independence Rock and South Pass on the Continental Divide.

Described as a 146-foot-tall turtle one mile in circumference, Independence Rock became the pioneers' much anticipated Register in the Desert, and a welcome stop after our long drive from Casper. Fifty-thousand who passed this way chiseled or painted their names, dates and initials on the smooth granite surface for posterity. Officially christened "Independence Rock" by William Sublette who led the first wagon train down this route in 1830, Sublette and his fellow travelers celebrated the Fourth of July with abandon. Emigrants who followed strove to reach the famous landmark, and nearby Sweetwater River, by Independence Day. If they succeeded they stood a better chance of reaching Oregon or California before the inevitable onslaught of deadly blizzards.

Lack of water and grass feed also plagued them during extended dry spells. Where water became available it sometimes was alkaline-poisoned. Despite written warnings posted near such water sources, some emigrants were illiterate and paid the ultimate price for their thirst and ignorance with a wretched, painful ending. Death and sickness were also transmitted, most likely, by ticks which infected the unknowing with Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever, particularly on that gradual 100-mile incline between Independence Rock and South Pass on the Continental Divide.

Described as a 146-foot-tall turtle one mile in circumference, Independence Rock became the pioneers' much anticipated Register in the Desert, and a welcome stop after our long drive from Casper. Fifty-thousand who passed this way chiseled or painted their names, dates and initials on the smooth granite surface for posterity. Officially christened "Independence Rock" by William Sublette who led the first wagon train down this route in 1830, Sublette and his fellow travelers celebrated the Fourth of July with abandon. Emigrants who followed strove to reach the famous landmark, and nearby Sweetwater River, by Independence Day. If they succeeded they stood a better chance of reaching Oregon or California before the inevitable onslaught of deadly blizzards.

With so many people on the trail simultaneously, Independence Rock became crowded, noisy, and it smelled. With the probable exception of the Mormon contingent, many celebrated their arrival and new unadulterated freedom with hard liquor, hard dancing, and careless gunfire. If you visit, beware of rattlesnakes, and be careful climbing the big rock because it's still slick like it was back then, and a long way down.

Between 1856 and 1860, three-thousand English and Scandinavian Mormons organized into ten handcart companies walked to Utah pulling 653 cumbersome two-wheeled handcarts, each laden with 400-500 pounds of vital supplies. But not everyone reached Independence Rock by the 4th of July. The Martin and Willie handcart companies got a late start, and despite dire warnings by one Levi Savage, departed present-day Omaha, Nebraska, in August of 1856 only to be trapped in the mountain-rimmed Sweetwater Valley during a monstrous October blizzard that claimed approximately 220 Mormon lives, and caused the eventual amputation of numerous limbs, toes, and fingers due to extreme frostbite.

With so many people on the trail simultaneously, Independence Rock became crowded, noisy, and it smelled. With the probable exception of the Mormon contingent, many celebrated their arrival and new unadulterated freedom with hard liquor, hard dancing, and careless gunfire. If you visit, beware of rattlesnakes, and be careful climbing the big rock because it's still slick like it was back then, and a long way down.

Between 1856 and 1860, three-thousand English and Scandinavian Mormons organized into ten handcart companies walked to Utah pulling 653 cumbersome two-wheeled handcarts, each laden with 400-500 pounds of vital supplies. But not everyone reached Independence Rock by the 4th of July. The Martin and Willie handcart companies got a late start, and despite dire warnings by one Levi Savage, departed present-day Omaha, Nebraska, in August of 1856 only to be trapped in the mountain-rimmed Sweetwater Valley during a monstrous October blizzard that claimed approximately 220 Mormon lives, and caused the eventual amputation of numerous limbs, toes, and fingers due to extreme frostbite.

Temperatures dropped to -11 Fahrenheit. The blizzard dumped 12-18 inches of snow, and many were drenched and suffering hypothermia and frostbite from having forded the icy North Platte River. To lighten their heavy loads, essential supplies, including blankets, food and clothing that could have saved lives, were regrettably discarded earlier. And to compound the disaster, they were sick and starving to death.

Heroic young women struggled to pull their carts through knee-deep snow while dying, emaciated young men lay prone in the back. Small children slogged through frozen mud. Old men stumbled and fell, and the weak and weary dropped in their tracks. Death was everywhere. Since the earth was frozen, the shallowest of graves were scratched into the rock-hard prairie, or the dearly-departed were left to the wolves and coyotes, on the bare, snow-covered ground. The train of misery stretched for miles.

Temperatures dropped to -11 Fahrenheit. The blizzard dumped 12-18 inches of snow, and many were drenched and suffering hypothermia and frostbite from having forded the icy North Platte River. To lighten their heavy loads, essential supplies, including blankets, food and clothing that could have saved lives, were regrettably discarded earlier. And to compound the disaster, they were sick and starving to death.

Heroic young women struggled to pull their carts through knee-deep snow while dying, emaciated young men lay prone in the back. Small children slogged through frozen mud. Old men stumbled and fell, and the weak and weary dropped in their tracks. Death was everywhere. Since the earth was frozen, the shallowest of graves were scratched into the rock-hard prairie, or the dearly-departed were left to the wolves and coyotes, on the bare, snow-covered ground. The train of misery stretched for miles.

Learning of the looming disaster, the Mormon leader Brigham Young in Salt Lake City sent rescue parties, initially ill-equipped, who located what remained of the Willie Company, and the Martin Company farther east. The rescuers’ efforts were nothing less than heroic. The manner in which the starving emigrants conducted themselves is to be commended because they didn't resort to eating each other as the Donner party did years earlier in California's Sierra Mountains. Wallace Stegner said it best when he wrote, “If courage and endurance make a story, if human-kindness and helpfulness and brotherly love in the midst of raw horror are worth recording, this half-forgotten episode of the Mormon migration is one of the great tales of the West and of America.”

Knowing this, the drive from Independence Rock to Martin's Cove was contemplative and melancholy. Traffic was non-existent as we rolled down the highway under ominous, gray skies watching low dark clouds hover near summits of granite mountains that populate the perimeter of the spacious valley. Two miles southeast of Martin's Cove I parked on a bluff overlooking the gentle turns of the Sweetwater and strolled down the circular path feeling alone and isolated in this remote corner of this least-populated state of Wyoming.

Learning of the looming disaster, the Mormon leader Brigham Young in Salt Lake City sent rescue parties, initially ill-equipped, who located what remained of the Willie Company, and the Martin Company farther east. The rescuers’ efforts were nothing less than heroic. The manner in which the starving emigrants conducted themselves is to be commended because they didn't resort to eating each other as the Donner party did years earlier in California's Sierra Mountains. Wallace Stegner said it best when he wrote, “If courage and endurance make a story, if human-kindness and helpfulness and brotherly love in the midst of raw horror are worth recording, this half-forgotten episode of the Mormon migration is one of the great tales of the West and of America.”

Knowing this, the drive from Independence Rock to Martin's Cove was contemplative and melancholy. Traffic was non-existent as we rolled down the highway under ominous, gray skies watching low dark clouds hover near summits of granite mountains that populate the perimeter of the spacious valley. Two miles southeast of Martin's Cove I parked on a bluff overlooking the gentle turns of the Sweetwater and strolled down the circular path feeling alone and isolated in this remote corner of this least-populated state of Wyoming.

Standing near the edge of the bluff I saw to my right another recognizable landmark, the narrow gash of Devil's Gate, a slot three-hundred-feet high cut by the river through sheer granite. To my surprise I also saw below me a swarm of people, and the residence, barns and old corrals of the historic Sun Ranch, first established back in 1872. The Sun Ranch epitomized the Wild West's ranching heritage and is now owned in part by the Mormon Church and operated as the Mormon Handcart Pioneer Visitors Center.

Dozens of automobiles, and tour buses, and hundreds of giddy Mormons dressed in pioneer garb - bonnets and long colorful plaid skirts - were reenacting the 19th-century handcart treks by pulling carts of their own just as their forefathers did up and down the original trail. While I expected a more somber tone in light of the 1856 blizzard, it nonetheless was a grand, happy celebration of their ancestors' heroic endeavors, and Mormonism in general.

Standing near the edge of the bluff I saw to my right another recognizable landmark, the narrow gash of Devil's Gate, a slot three-hundred-feet high cut by the river through sheer granite. To my surprise I also saw below me a swarm of people, and the residence, barns and old corrals of the historic Sun Ranch, first established back in 1872. The Sun Ranch epitomized the Wild West's ranching heritage and is now owned in part by the Mormon Church and operated as the Mormon Handcart Pioneer Visitors Center.

Dozens of automobiles, and tour buses, and hundreds of giddy Mormons dressed in pioneer garb - bonnets and long colorful plaid skirts - were reenacting the 19th-century handcart treks by pulling carts of their own just as their forefathers did up and down the original trail. While I expected a more somber tone in light of the 1856 blizzard, it nonetheless was a grand, happy celebration of their ancestors' heroic endeavors, and Mormonism in general.

Since visitors are welcome and entrance is free, we strolled about the sprawling complex of log cabins and other old structures transported back in time. The vast collection of artifacts was impressive; revolvers and rifles, battered cookware, coffee grinders, arrows and moccasins, long skirts and tattered books, hand tools and crooked wagons and old leather boots and dull axes and such. The museums and replicas are literally crammed with the history of the white man's American West. A stop at the Interpretive Center is highly recommended, even if you're not Mormon. Don't worry, they won't bite.

South Pass on the Continental Divide looks today much like it did to the emigrants, a low, nondescript rise on the treeless, sage-covered expanse within view of the rugged Wind River Range to the north. After crossing South Pass the rolling sea of humanity broke apart as the trail fanned out in three general directions over a series of cutoffs and shortcuts. Trail ruts are visible all over the place if you know where to look, in some instances right beside the highway. You'll recognize them because they are very narrow, and generally point east or west.

Since visitors are welcome and entrance is free, we strolled about the sprawling complex of log cabins and other old structures transported back in time. The vast collection of artifacts was impressive; revolvers and rifles, battered cookware, coffee grinders, arrows and moccasins, long skirts and tattered books, hand tools and crooked wagons and old leather boots and dull axes and such. The museums and replicas are literally crammed with the history of the white man's American West. A stop at the Interpretive Center is highly recommended, even if you're not Mormon. Don't worry, they won't bite.

South Pass on the Continental Divide looks today much like it did to the emigrants, a low, nondescript rise on the treeless, sage-covered expanse within view of the rugged Wind River Range to the north. After crossing South Pass the rolling sea of humanity broke apart as the trail fanned out in three general directions over a series of cutoffs and shortcuts. Trail ruts are visible all over the place if you know where to look, in some instances right beside the highway. You'll recognize them because they are very narrow, and generally point east or west.

From here our forefathers marched on to the lush green valleys of Oregon and the Northwest, and across the barren, brown wastelands of Nevada to California and the gold mines and bountiful central valleys. Mormon pioneers continued southwest to Fort Bridger and the Valley of the Salt Lake in the shadow of the towering Wasatch Mountains on the edge of the Great Desert Basin, a land called Zion. By all accounts this last stretch along the Mormon Trail up and over the mountains was the most difficult, the most challenging, unless you were caught in an early winter blizzard in the beautiful Sweetwater Valley in October of 1856 pulling an overloaded handcart, starving to death.

From here our forefathers marched on to the lush green valleys of Oregon and the Northwest, and across the barren, brown wastelands of Nevada to California and the gold mines and bountiful central valleys. Mormon pioneers continued southwest to Fort Bridger and the Valley of the Salt Lake in the shadow of the towering Wasatch Mountains on the edge of the Great Desert Basin, a land called Zion. By all accounts this last stretch along the Mormon Trail up and over the mountains was the most difficult, the most challenging, unless you were caught in an early winter blizzard in the beautiful Sweetwater Valley in October of 1856 pulling an overloaded handcart, starving to death.View Comments

John Treadwell Dunbar is a freelance writer