The St Bartholomew's Day Massacre began when Admiral Gaspard de Coligny, leader of the Huguenots, was assassinated in his room, and his body dragged through the streets, bereft of head, hands and genitals, according to John Witte, Jr. in

The Reformation of Rights. It did not help to tamp down conspiracy speculations that the head of the government was Catherine de Medici, daughter of the man to whom Niccolo Machiavelli dedicated his infamous, godless masterpiece, The Prince.

Francois Hotman

Francois Hotman, in his immortal

Francogallia, helped broaden the appeal of Huguenot Right of Resistance theory by suggesting that the lesser officials the Lutherans termed "magistrates," that they stated were appointed by God, were just as importantly man-chosen representatives. This presaged a larger move away from religious to secular theories in the Huguenot defensive strategy. But Hotman's work, which used an historical approach to suggest ancient kings were chosen by the people, and therefore should be seen as representative authorities, was simply not up to the task of creating a modern argument for Resistance against current, unjust authority.

But a need for such a cutting-edge theory bubbled under the surface of French society. Suffice it to say that the intrigue which surrounded Catherine de Medici made certain as to stoke the fires of fear and create an incipient sense of the need for a theory of self-defense. This, as much as any other factor, helped push the Calvinist Huguenots towards developing a robust theory of self-defense and Right of Resistance.

II. Calvin, Beza & Mornay: Natural Law Theory

The need for an updated theory of the Right of Resistance was acutely felt by the Huguenot community, certain another government-sponsored massacre was right around the corner.

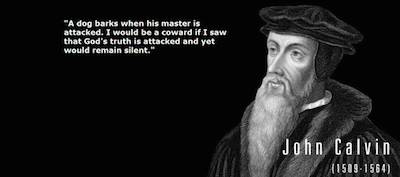

John Calvin

John Calvin, regarded the greatest Protestant theologian in history, and the leader of the church in Geneva, was a reluctant supporter of Resistance Theory. Yet, toward the end of his life, the famously cautious author moved closer to embracing the need for allowing spirited rejection of the powers that be, under certain, well-proscribed circumstances.

Needing a strong fix, the next generation of rights theory turned to the Natural Law, scholasticism and Roman law radical constitutionalism, claims Skinner. They argued that earliest mankind lived a nomadic existence of radical liberty. Humans were consumed with simple survival, unencumbered by society or legal restriction. And it was only when men began to live a settled existence, that some tried to deprive the liberty of others. In such a society of total freedom, any legitimate government must be built from the consent of all members.

Theodore Beza

These writers of the new Calvinist Resistance Theory, such as Theodore Beza and Philippe de Mornay, hearkened back to Catholic Concilliar Theory, which placed the locus of authority not in the Pope, but in the see of Cardinals. It is therefore ironic that the materials used to build Calvinist Resistance Theory were all borrowed from earlier Catholic thinkers. This is easier to understand when we consider the Huguenots needed to persuade the French society at large, still mostly Catholic in its sentiments.

Theodore Beza (1519-1605) was a French Protestant Christian theologian and scholar was the handpicked successor to Calvin. He wrote,

If the magistrate rules properly, the people, must obey him. But if the magistrate exceeds his authority, the people, through their representatives, have not only the right but also the duty of conscience to resist such tyranny. No magistrate should be suffered who has fundamentally breached the covenant he had sworn to God and his people. To suffer such a tyrant would insult God who had called all rulers to represent his divine being and authority on earth and to strive for divine justice and equity for all of God's people.

Philippe de Mornay

Philippe de Mornay (1549-1623) was a French

military captain, a diplomat, a man of letters and a theologian. He offered a sophisticated view of a proper society, stating that a good commonwealth is established by at least the consent of the majority, which he based upon the installation of Saul as King in Israel. In the

Quaestio of his

Defense, Mornay establishes that all persons were living in a state of liberty before entering society. Further, that the only purpose for the existence of leaders is the protection and security of the people, especially of their natural rights. And that whenever the leader fails to protect these rights, but menaces them, the people have a natural right to remove the leader. John Locke would take up these same themes a century later.

Mornay details that in a large state, it is acceptable, and even inevitable that representatives be chosen for the people. Further, the relationship is stated as a contract, with covenants between the king and God, the people and God, and the people and the king. The contract, or

Lex Regia, is explicitly set up between the king and the people, and is predicated upon the king pursuing the welfare of the people and protecting their rights. But the agreement between the people and the king is a secular contract, or a

pactum, and not a religious agreement, or

foedus--covenant.

Mornay goes on to explain the duty of the people to the king is conditional, but the reciprocal duty of the king to the people is absolute--because the king arises from the people, but not the people from the king. The king who fails to protect the people and their rights is a tyrant, whereas if the people act without fidelity, they are seditious. The doctrine of Popular Sovereignty naturally arises from such an understanding, while the Right of Resistance is merely a natural outcome of the leader's manifest failure.

Calvinist Resistance Theory v. Thomism

And herein lies a disagreement between two rival camps. The Huguenots taught that since all persons naturally live in freedom, until entering society--but will only remain as long as their king is not a tyrant, then the authority always lies with the people. Conversely, the Thomist camp, which contains Aquinas, Grotius and Pufendorf teach the king, as

legibus solutus, is an absolute sovereign. He enjoys an absolute right to all actions, and is above even his own laws, while in office.

This pseudo-papist argument is confuted by the church's Conciliar Theory. Further, John Locke decisively rejects this argument from the pen of Robert Filmer and his Divine Right of Kings, first articulated by the French Bodin. Beza teaches that the king, as a servant of the commonwealth--

servus republicae--is under every single law, just as any other citizen. Beza writes, "there is not a single law to which the ruler is not bound in the conduct of his government, since he has sworn to be the protector and preserver of them all." Thus, the right of popular resistance is also a duty.

The works of Beza and Mornay signaled the end of the notion that the only acceptable theory of the Right of Resistance was religious. Instead, two covenants existed in the society, representing both religion and secular rule. Therefore arose a theory of defensible popular revolt based upon natural law and the natural rights of citizens in defense of their popular sovereignty and natural rights.

III. Scotland, Buchanan & the Secular Right of Popular Resistance

George Buchanan

Scotland became the most Calvinist of nations in spite of Catholic Queen Mary. This caused the Calvinists to restate their religious duties as secular rights, until she was deposed. And it was the humanist trained, Reform minded

George Buchanan (1506-1582) who helped create the arguments necessary for the first Calvinist revolution, in his

Right of the Kingdom in Scotland. Buchanan criticized corruption in church and state during the Scottish Reformation. He was famed as a scholar and a Latin poet.

As a humanist, Buchanan accepted the stoic version of the rise of mankind, quoting Cicero, who wrote, "There was a time when men wandered at large in the fields like animals," until society finally arose. Interestingly, Buchanan evolves the theory so completely from the Huguenots that he never even mentions the covenant with God, making society's relationship with its king purely secular. This maneuver was echoed by Johannes Althuis in his highly influential

Politics. This maneuver allowed the Reformers to present a theory which not only avoided sectarianism, but also represented every member of society, religious, or not.

This sea-change represents the transition from theology to politics, and from religious duties to natural rights. Buchanan then developed a radical theory of popular sovereignty. While there may be intermediary leaders who assist in the duties of the kingdom, these are mere secular ministers, who do not claim sovereignty, which stays with the people. Therefore, leaders are chosen directly by the people, who also retain the right to be directly involved with his removal for cause.

IV. Mariana's Jesuit Catholic Right of Popular Resistance

Finally, the radical Jesuit Father

Juan de Mariana (1536-1624), in his work

The King and the Education of the King, in Book VI, asks if a tyrannical king can be removed? After mentioning the preferred method of removal by Assembly, Mariana then states that since it is the people that seat the king, they can also remove him, because a king is merely on the level of a paid employee, being a helmsman and guide

(gubernator, rector). Further, while exploring what happens when the Assembly does not remove the king, Mariana allows that a private citizen may do any action himself to remove the king without fear of breaking the law or acting immorally.

Conclusion

In this second installment of the development of the Right of Resistance to bad rulers, we see how the Reformers created a theory which was based upon Natural Law and Roman jurisprudence, not merely biblical precepts. By the time Buchanan and Mariana were finished, there was no more agreement between God, only the people and the king. And this was based wholly upon the free will of the people. Moreover, the king could be removed directly by the people, who no longer needed to wait for the lesser-magistrates to act. This is because the people had a radical version of popular sovereignty, and acted directly to install the king--who if he did not protect the safety and natural rights of the people--could be directly removed.

In the next essay, the last in the series, we will consider how John Locke put the theory of Right to Resistance into his own words, which the American Founders then used to justify the US War of Independence, which merely changed the entire world.