By John Treadwell Dunbar ——Bio and Archives--March 30, 2012

Travel | CFP Comments | Reader Friendly | Subscribe | Email Us

They came. They built. They vanished. Unique among Native American prehistoric civilizations, the gradual rise and terribly swift fall of the Ancient Pueblo Indians of America's Southwest, the Anasazi, continues to transfix modern man. Understandably, admiration for the ancients' beautiful architectural triumphs and preconceived notions about this relatively peaceful utopian civilization of farmers have been tarnished by what is considered heresy among many archeologists and self-proclaimed descendants of the Anasazi - the Hopi, Zuni and other pueblo peoples.

According to experts in the field, and others, it appears as though they ate each other, or were sacrificed and devoured between the ninth and 12th centuries by a ruling elite of Mesoamerican cannibals intent on maintaining their grip on power through sheer terror. Or maybe they were gobbled up in the 1100s by invading hordes from Old Mexico, the Toltecs. Regardless of who perpetrated this unseemly culinary tradition, or why, it's virtually certain that human sacrifice and the feast that followed were not limited to country folk in far-flung communities, but likely practiced in a big way in the big city at Chaco Canyon as well. The debate rages on.

They came. They built. They vanished. Unique among Native American prehistoric civilizations, the gradual rise and terribly swift fall of the Ancient Pueblo Indians of America's Southwest, the Anasazi, continues to transfix modern man. Understandably, admiration for the ancients' beautiful architectural triumphs and preconceived notions about this relatively peaceful utopian civilization of farmers have been tarnished by what is considered heresy among many archeologists and self-proclaimed descendants of the Anasazi - the Hopi, Zuni and other pueblo peoples.

According to experts in the field, and others, it appears as though they ate each other, or were sacrificed and devoured between the ninth and 12th centuries by a ruling elite of Mesoamerican cannibals intent on maintaining their grip on power through sheer terror. Or maybe they were gobbled up in the 1100s by invading hordes from Old Mexico, the Toltecs. Regardless of who perpetrated this unseemly culinary tradition, or why, it's virtually certain that human sacrifice and the feast that followed were not limited to country folk in far-flung communities, but likely practiced in a big way in the big city at Chaco Canyon as well. The debate rages on. While trade goods no doubt were transported along the primary thoroughfares - macaws from southern Mexico (they were partial to the feathers), sea shells from the ocean, copper bells, ceramics and turquoise - today's Navajo and notable archaeologists believe the major arteries were used primarily for transporting timber to Chaco Canyon from forested mountains like the Chuskas fifty miles to the west. It's estimated 200,000 trees were used in constructing Chaco's structures. Considering the Anasazi had no draft animals and walked everywhere, in crude sandals no less, their accomplishments were all that more admirable. On the other hand, some archeologists believe the roads, initially, played religious and ceremonial roles due in part to their alignment, and the fact that some don't seem to go anywhere in particular.

While trade goods no doubt were transported along the primary thoroughfares - macaws from southern Mexico (they were partial to the feathers), sea shells from the ocean, copper bells, ceramics and turquoise - today's Navajo and notable archaeologists believe the major arteries were used primarily for transporting timber to Chaco Canyon from forested mountains like the Chuskas fifty miles to the west. It's estimated 200,000 trees were used in constructing Chaco's structures. Considering the Anasazi had no draft animals and walked everywhere, in crude sandals no less, their accomplishments were all that more admirable. On the other hand, some archeologists believe the roads, initially, played religious and ceremonial roles due in part to their alignment, and the fact that some don't seem to go anywhere in particular.

A one-way paved road will loop you down Chaco Canyon seven miles and return you back to the visitors center. This route provides access to several trailheads and numerous complexes; Una Vida, Chetro Ketl, Pueblo Alto on top of the mesa, Kin Kletso, Pueblo del Arroyo and Casa Rinconada, and others. But the flagship of this vast urban center, which by 1050 had become the economic, administrative and ceremonial headquarters of the San Juan Basin, was Pueblo Bonito at the far end of the canyon. It was occupied from the mid-800s to the 1200s and became the beating heart of this remarkable culture.

A one-way paved road will loop you down Chaco Canyon seven miles and return you back to the visitors center. This route provides access to several trailheads and numerous complexes; Una Vida, Chetro Ketl, Pueblo Alto on top of the mesa, Kin Kletso, Pueblo del Arroyo and Casa Rinconada, and others. But the flagship of this vast urban center, which by 1050 had become the economic, administrative and ceremonial headquarters of the San Juan Basin, was Pueblo Bonito at the far end of the canyon. It was occupied from the mid-800s to the 1200s and became the beating heart of this remarkable culture.

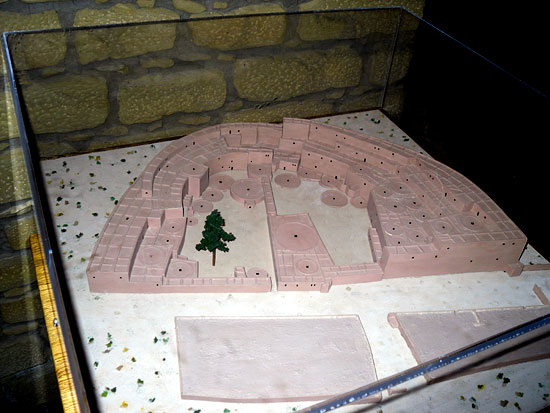

Likened to the Roman Coliseum, but not quite as big, the neatly stacked remains of Pueblo Bonito is the largest and grandest "Great House" in Chaco Canyon, and recently struck me with awe much as it did in 1979 when I first laid eyes on those sun-lit blocks of stone at the crack of dawn one fine spring morning. Built with 30,000 tons of sandstone blocks, and shaped in the letter 'D' near the base of 200-foot-high sandstone cliffs, Pueblo Bonito, like most of the area's dominant structures, wasn't built in fits and starts as the need arose, but was planned in advance, designed and constructed one large section at a time. This massive complex rose to a height of four or five stories along the curving, outer back wall, and was comprised of over 600 rooms stacked and progressively tiered. Exterior masonry walls were up to three feet thick, and a large open plaza dominated the complex's interior.

Likened to the Roman Coliseum, but not quite as big, the neatly stacked remains of Pueblo Bonito is the largest and grandest "Great House" in Chaco Canyon, and recently struck me with awe much as it did in 1979 when I first laid eyes on those sun-lit blocks of stone at the crack of dawn one fine spring morning. Built with 30,000 tons of sandstone blocks, and shaped in the letter 'D' near the base of 200-foot-high sandstone cliffs, Pueblo Bonito, like most of the area's dominant structures, wasn't built in fits and starts as the need arose, but was planned in advance, designed and constructed one large section at a time. This massive complex rose to a height of four or five stories along the curving, outer back wall, and was comprised of over 600 rooms stacked and progressively tiered. Exterior masonry walls were up to three feet thick, and a large open plaza dominated the complex's interior.

Throughout Pueblo Bonito one finds the circular remains of forty kivas, sunken rooms originally flat-topped and accessible by ladder through a hole in the roof. Kivas have achieved iconic status in the Southwest - they're round - and were central to the ancients' religious life. They also served as ceremonial, social and political gathering places. Some kivas in Chaco Canyon were very large, accommodated great crowds and were free-standing. They may have towered two to three stories high, though most were smaller and clustered together. From a photographer's perspective, the resulting patterns laid down by the ruins are intriguing, particularly at Pueblo Bonito and Chetro Ketl where the kivas' gentle curves are juxtaposed beside the ordered symmetry of rectangular boxed rooms and stone walls teetering on collapse.

Throughout Pueblo Bonito one finds the circular remains of forty kivas, sunken rooms originally flat-topped and accessible by ladder through a hole in the roof. Kivas have achieved iconic status in the Southwest - they're round - and were central to the ancients' religious life. They also served as ceremonial, social and political gathering places. Some kivas in Chaco Canyon were very large, accommodated great crowds and were free-standing. They may have towered two to three stories high, though most were smaller and clustered together. From a photographer's perspective, the resulting patterns laid down by the ruins are intriguing, particularly at Pueblo Bonito and Chetro Ketl where the kivas' gentle curves are juxtaposed beside the ordered symmetry of rectangular boxed rooms and stone walls teetering on collapse.

Reflecting the surrounding high desert, cliffs, and boulders that line the canyon, Chaco's ruins appear mundane and subdued by earthy browns and the deep reds. But one must not think of ancient Chaco as bland. Blue, yellow, red, green and white pigment stains were extracted from a variety of minerals and used to brighten up this thriving urban center that bustled with hundreds, even thousands, of men, women and children. And what they left behind has provided modern man a veritable window into their complex past.

Over 4,000 sites in the park have been identified so far, most of which are prehistoric, and many of those have been excavated, tested and legally pilfered for posterity and preservation. Many, if not most, of the artifacts were gathered between 1970 and 1985 and cover each cultural time period, such as the Archaic, Basketmaker and Pueblo eras. We also know about their natural environment through the collection and study of tree-ring-dating wood samples, soil and mineral samples, pollen and botanical specimens, and rat middens, or dung-heaps, all of which bring today's quiet, crumbling ruins to life and enriches our understanding of these short but stocky, sun-burned people.

Reflecting the surrounding high desert, cliffs, and boulders that line the canyon, Chaco's ruins appear mundane and subdued by earthy browns and the deep reds. But one must not think of ancient Chaco as bland. Blue, yellow, red, green and white pigment stains were extracted from a variety of minerals and used to brighten up this thriving urban center that bustled with hundreds, even thousands, of men, women and children. And what they left behind has provided modern man a veritable window into their complex past.

Over 4,000 sites in the park have been identified so far, most of which are prehistoric, and many of those have been excavated, tested and legally pilfered for posterity and preservation. Many, if not most, of the artifacts were gathered between 1970 and 1985 and cover each cultural time period, such as the Archaic, Basketmaker and Pueblo eras. We also know about their natural environment through the collection and study of tree-ring-dating wood samples, soil and mineral samples, pollen and botanical specimens, and rat middens, or dung-heaps, all of which bring today's quiet, crumbling ruins to life and enriches our understanding of these short but stocky, sun-burned people.

This vast treasure trove of artifacts and relics unearthed at Chaco beginning in the early 20th century attests to the rich diversity of Chacoan culture. Over one million ancient archeological objects, a staggering number, have been collected over the years; hoes and hammers, mauls and digging sticks, turkey bones and corn cobs, shards and lithics, yucca sandals and reed matting, bone tools, stone tools, ceramic vessels - much pottery elaborately detailed in geometric black-and-white patterns - turquoise and shell ornaments, and arrow heads. The Anasazi were particularly fond of carved pendants, and obsessed with beadwork. Two burial plots at Pueblo Bonito alone contained over 15,000 beads and pendants.

Try, and with a little imagination you can envision crumbled walls magically reassembled to their original height, covered in plaster and decorated with murals now long gone. Roofless kivas and square-cornered rooms exposing dirt floors to direct sunlight are covered with flat tops banishing sun and sky, turning things dark and cozy inside, if not a bit ripe.

This vast treasure trove of artifacts and relics unearthed at Chaco beginning in the early 20th century attests to the rich diversity of Chacoan culture. Over one million ancient archeological objects, a staggering number, have been collected over the years; hoes and hammers, mauls and digging sticks, turkey bones and corn cobs, shards and lithics, yucca sandals and reed matting, bone tools, stone tools, ceramic vessels - much pottery elaborately detailed in geometric black-and-white patterns - turquoise and shell ornaments, and arrow heads. The Anasazi were particularly fond of carved pendants, and obsessed with beadwork. Two burial plots at Pueblo Bonito alone contained over 15,000 beads and pendants.

Try, and with a little imagination you can envision crumbled walls magically reassembled to their original height, covered in plaster and decorated with murals now long gone. Roofless kivas and square-cornered rooms exposing dirt floors to direct sunlight are covered with flat tops banishing sun and sky, turning things dark and cozy inside, if not a bit ripe.

Meandering from room to room at Pueblo Bonito, your trusty self-guided tour book in hand, you'll realize how architecturally sophisticated these people were as you bend over and squeeze through small doorways, pausing to watch Jane Anasazi standing over a blackened pot, panting in the heat, stirring the family's remaining handful of beans, maybe some squash, a hint of wild turkey parts mechanically separated, and the last of the brown water. The amber glow cast by the fire's flame bends the starving woman's shadow across the wall, while her naked infants, Mabel and Alfred, squat underfoot playing with the floor. It's smoky, and on its perch high in the corner a beautiful scarlet macaw squawks once, then twice, sensing that it's next on the menu unless things improve around here, and soon.

Meandering from room to room at Pueblo Bonito, your trusty self-guided tour book in hand, you'll realize how architecturally sophisticated these people were as you bend over and squeeze through small doorways, pausing to watch Jane Anasazi standing over a blackened pot, panting in the heat, stirring the family's remaining handful of beans, maybe some squash, a hint of wild turkey parts mechanically separated, and the last of the brown water. The amber glow cast by the fire's flame bends the starving woman's shadow across the wall, while her naked infants, Mabel and Alfred, squat underfoot playing with the floor. It's smoky, and on its perch high in the corner a beautiful scarlet macaw squawks once, then twice, sensing that it's next on the menu unless things improve around here, and soon.

Facing the corner on his knees with head bowed is Jane's husband, Joe, near defeat and pleading with a small clay idol statue he believes to be a god, his personal god named Zani-Moki (“Give-Me-Stuff”), the head deity of a new religion he read about on the back cover of Popular Mechanics. He thought he'd give Zani-Moki a try. After all, nothing else was working. He begs for mercy and relief, a miracle, something, anything, that will deliver his family from the grueling drought that was baking the Southwest and charbroiling the entire San Juan Basin. His thoughts tumble around the inside of his simple mind, searching for a way out, a way to express themselves concretely. He wants desperately to put words to parchment, make a to-do list, send his pigeon for help, maybe start a diary, put order to the disorder. He sighs on behalf of all Anasazi, thinking, "If only we had a written language."

A perfect storm of want and desperation engulfed Chaco in the 1100s. Due to over-consumption, gone were the juniper and pine forests that covered the land and the canyon bottom. Edible plant life and habitat shriveled up. Shallow water courses previously dammed became dust bowls; granaries full of corn, squash and beans were becoming depleted. The Anasazi of the 12th century became perilously iron deficient from a lack of protein. They craved meat, but the last of the rats, beaver, rabbits and prairie dogs hopped off or scurried away long ago, or had been trapped and devoured in a desperate last-ditch panic.

Facing the corner on his knees with head bowed is Jane's husband, Joe, near defeat and pleading with a small clay idol statue he believes to be a god, his personal god named Zani-Moki (“Give-Me-Stuff”), the head deity of a new religion he read about on the back cover of Popular Mechanics. He thought he'd give Zani-Moki a try. After all, nothing else was working. He begs for mercy and relief, a miracle, something, anything, that will deliver his family from the grueling drought that was baking the Southwest and charbroiling the entire San Juan Basin. His thoughts tumble around the inside of his simple mind, searching for a way out, a way to express themselves concretely. He wants desperately to put words to parchment, make a to-do list, send his pigeon for help, maybe start a diary, put order to the disorder. He sighs on behalf of all Anasazi, thinking, "If only we had a written language."

A perfect storm of want and desperation engulfed Chaco in the 1100s. Due to over-consumption, gone were the juniper and pine forests that covered the land and the canyon bottom. Edible plant life and habitat shriveled up. Shallow water courses previously dammed became dust bowls; granaries full of corn, squash and beans were becoming depleted. The Anasazi of the 12th century became perilously iron deficient from a lack of protein. They craved meat, but the last of the rats, beaver, rabbits and prairie dogs hopped off or scurried away long ago, or had been trapped and devoured in a desperate last-ditch panic.

These little people in cracked, leathery skin were dying of thirst and hunger, and the Joe Anasazi family was no exception. He was in denial and one of the remaining holdouts at half-empty Pueblo Bonito. He couldn't bring himself to pack up his family and leave with the others, migrate north or south or east or west like his brethren who finally caved in to the desperation and staggered off into the luminescent orange sunset.

The stubborn, proud man in soiled loincloth sat chewing his filthy fingernails and continued praying, confident that his clay idol would deliver them from all this evil. But Jane knew better. She stood by the last fire they would ever make and stirred their last pot of grub, fretting and twisting the long strands of her black hair, fearing the worst, imagining the unimaginable. What if the rumors filtering up from the south were true? What if the horror stories that sent others fleeing in sheer panic were true?

These little people in cracked, leathery skin were dying of thirst and hunger, and the Joe Anasazi family was no exception. He was in denial and one of the remaining holdouts at half-empty Pueblo Bonito. He couldn't bring himself to pack up his family and leave with the others, migrate north or south or east or west like his brethren who finally caved in to the desperation and staggered off into the luminescent orange sunset.

The stubborn, proud man in soiled loincloth sat chewing his filthy fingernails and continued praying, confident that his clay idol would deliver them from all this evil. But Jane knew better. She stood by the last fire they would ever make and stirred their last pot of grub, fretting and twisting the long strands of her black hair, fearing the worst, imagining the unimaginable. What if the rumors filtering up from the south were true? What if the horror stories that sent others fleeing in sheer panic were true?

A shudder set her shoulders a-twitching and her knees a-knocking. Setting aside her ladle, she shuffled over to her husband one more time and knelt beside him, cupped his chin in her dirty hand, and turned his head into the wavering light. Though she loved Joe, she wasn't in love with him and secretly thought of ways to dump the old boy. Truth be told, she had a thing for Frank, the sandal-maker, who took off for Sand Island last week and was waiting for her and the kids. She wanted so much to run away with her secret lover, and the others, to someplace exotic; start over, take up needlepoint, learn to rumba, maybe splurge on a facial. She chose her words carefully and tried to reason with her boring husband.

Joe shook his head in defiance and turned back to the idol. Feeling the onslaught of another panic attack, his wife grabbed him by the shoulders and shook him violently. "Snap out of it, you moron. It's just a piece of clay!" And that's when they heard the knock at the door.

A shudder set her shoulders a-twitching and her knees a-knocking. Setting aside her ladle, she shuffled over to her husband one more time and knelt beside him, cupped his chin in her dirty hand, and turned his head into the wavering light. Though she loved Joe, she wasn't in love with him and secretly thought of ways to dump the old boy. Truth be told, she had a thing for Frank, the sandal-maker, who took off for Sand Island last week and was waiting for her and the kids. She wanted so much to run away with her secret lover, and the others, to someplace exotic; start over, take up needlepoint, learn to rumba, maybe splurge on a facial. She chose her words carefully and tried to reason with her boring husband.

Joe shook his head in defiance and turned back to the idol. Feeling the onslaught of another panic attack, his wife grabbed him by the shoulders and shook him violently. "Snap out of it, you moron. It's just a piece of clay!" And that's when they heard the knock at the door.

Depending on your sources, by the 1200s the Anasazi of Chaco Canyon had vanished into thin air, and by the 1300s that entire civilization throughout the Southwest disappeared. It is one of the great archeological and anthropological mysteries yet to be solved, though many theories have been advanced. A crippling 50-year drought appears to be the seminal culprit; a lack of water lead to inevitable crop failure and famine.

Overpopulation meant the over-consumption of wildlife and other meat sources. Forest products - trees - were depleted which contributed to erosion, cold meals and frigid winter nights. Plague could have thinned the masses in one fell swoop. Some theorize a religious mass exodus lead them away, or maybe they just got tired of the place and walked off to greener pastures and wetter streams. And who can blame them? This place is dry and dusty, and that's in a good year.

Depending on your sources, by the 1200s the Anasazi of Chaco Canyon had vanished into thin air, and by the 1300s that entire civilization throughout the Southwest disappeared. It is one of the great archeological and anthropological mysteries yet to be solved, though many theories have been advanced. A crippling 50-year drought appears to be the seminal culprit; a lack of water lead to inevitable crop failure and famine.

Overpopulation meant the over-consumption of wildlife and other meat sources. Forest products - trees - were depleted which contributed to erosion, cold meals and frigid winter nights. Plague could have thinned the masses in one fell swoop. Some theorize a religious mass exodus lead them away, or maybe they just got tired of the place and walked off to greener pastures and wetter streams. And who can blame them? This place is dry and dusty, and that's in a good year.

These factors, and others, could have congealed into a cauldron of catastrophes that collectively brought down the Anasazi. Take your pick, though any one of these scenarios would make for a boring motion picture; gradual starvation and sickness are not engaging plot lines. If I were writing the script I'd go with option 'D' and throw in the man-eaters, invading Toltec cannibals from southern Mexico who, on arriving in drought-stricken Northwest New Mexico found nothing for lunch except a few starving Anasazi dirt farmers staggering around in a hungry daze too weak to flee or fight.

These factors, and others, could have congealed into a cauldron of catastrophes that collectively brought down the Anasazi. Take your pick, though any one of these scenarios would make for a boring motion picture; gradual starvation and sickness are not engaging plot lines. If I were writing the script I'd go with option 'D' and throw in the man-eaters, invading Toltec cannibals from southern Mexico who, on arriving in drought-stricken Northwest New Mexico found nothing for lunch except a few starving Anasazi dirt farmers staggering around in a hungry daze too weak to flee or fight.

For the most part, the idea of cannibalism, particularly at the wholesale level, has been anathema to mainstream archeologists and others in the field, and any such suggestion has been deemed racist, insensitive and politically incorrect. The Hopi and other contemporary descendants of the Anasazi are particularly incensed at the very thought of their noble ancestors partaking of human flesh, even though it appears from strong evidence uncovered during the past forty years that cannibalism was a sad fact of Anasazi life.

The chief proponent of this unsettling theory is Professor Christy Turner, and his wife Jacqueline, who devoted considerable time and energy examining the evidence. Publishing a 500-page tome of their findings and analysis in 1999 entitled, "Man Corn: Cannibalism and Violence in the Prehistoric American Southwest," the authors examined 72 Anasazi sites, most of which showed signs of cannibalism or brute violence and mutilation. Of those sites, 38 were most likely "charnel deposits," heaps of cannibalized remains of men, women, and even children. Some sites contained the remains of as many as 35 people, which converts roughly to one ton of meat, enough to feed a large war party. It's quite possible, then, if not probable, that no less than 300 people were chopped up, barbequed, boiled or fried, and eaten in this study alone. The title of the Turners' book, "Man Corn," is fitting, a literal translation of the Aztec word "tlacatlaolli," which refers to (hold on to your stomach) "a sacred meal of sacrificed human meat, cooked with corn, a side of fries and chocolate ice cream for desert (drinks not included)"; a disgusting high-protein, but certainly well-balanced, diet.

For the most part, the idea of cannibalism, particularly at the wholesale level, has been anathema to mainstream archeologists and others in the field, and any such suggestion has been deemed racist, insensitive and politically incorrect. The Hopi and other contemporary descendants of the Anasazi are particularly incensed at the very thought of their noble ancestors partaking of human flesh, even though it appears from strong evidence uncovered during the past forty years that cannibalism was a sad fact of Anasazi life.

The chief proponent of this unsettling theory is Professor Christy Turner, and his wife Jacqueline, who devoted considerable time and energy examining the evidence. Publishing a 500-page tome of their findings and analysis in 1999 entitled, "Man Corn: Cannibalism and Violence in the Prehistoric American Southwest," the authors examined 72 Anasazi sites, most of which showed signs of cannibalism or brute violence and mutilation. Of those sites, 38 were most likely "charnel deposits," heaps of cannibalized remains of men, women, and even children. Some sites contained the remains of as many as 35 people, which converts roughly to one ton of meat, enough to feed a large war party. It's quite possible, then, if not probable, that no less than 300 people were chopped up, barbequed, boiled or fried, and eaten in this study alone. The title of the Turners' book, "Man Corn," is fitting, a literal translation of the Aztec word "tlacatlaolli," which refers to (hold on to your stomach) "a sacred meal of sacrificed human meat, cooked with corn, a side of fries and chocolate ice cream for desert (drinks not included)"; a disgusting high-protein, but certainly well-balanced, diet.

According to Mr. Turner, for humans back then to be considered cannibalized their remains must pass a series of tests. Bones had to be broken open for the marrow and covered in saw and cutting marks as though they were butchered and dismembered. Some of the bones must show "anvil abrasions," particularly on skulls which indicated attempts to crush them between two rocks. Burned bone fragments were required, particularly skulls, because severed heads were often placed face-up in a fire's coals to cook the brain. Yes, the brain. Furthermore, most of the spongy bone and vertebrae had to be missing, crushed for bone cakes or boiled for the grease.

Turner's criteria for establishing cannibalism (anthropophagy) also included "pot polish," a theory substantiated by noted paleoanthropologist Tim D. White. Pot polish is found on the ends of bones cooked in a ceramic pot for the fat which floats to the top and is skimmed off. As the bones are stirred, the ends in contact with the inside of the pot become polished with microscopic abrasions.

According to Mr. Turner, for humans back then to be considered cannibalized their remains must pass a series of tests. Bones had to be broken open for the marrow and covered in saw and cutting marks as though they were butchered and dismembered. Some of the bones must show "anvil abrasions," particularly on skulls which indicated attempts to crush them between two rocks. Burned bone fragments were required, particularly skulls, because severed heads were often placed face-up in a fire's coals to cook the brain. Yes, the brain. Furthermore, most of the spongy bone and vertebrae had to be missing, crushed for bone cakes or boiled for the grease.

Turner's criteria for establishing cannibalism (anthropophagy) also included "pot polish," a theory substantiated by noted paleoanthropologist Tim D. White. Pot polish is found on the ends of bones cooked in a ceramic pot for the fat which floats to the top and is skimmed off. As the bones are stirred, the ends in contact with the inside of the pot become polished with microscopic abrasions.

Ancient human excrement, or coprolite, discovered near a charnel heap, provided the missing link that proved humans ate humans. After rigorous testing it was determined that the coprolite contained the human protein myoglobin, which is only found in heart muscle and skeletal muscle, and which can only enter the intestines if eaten. Myoglobin was also discovered on the inside of a cooking pot. It should be the final nail in the skeptics' coffin.

Despite this proof, many critics were outraged and attempted to explain away these findings. Some went so far as to claim there never were such things as cannibals, anywhere, ever. Others argue these were isolated incidents. Perhaps those eaten were deserving witches, or sworn enemies who had it coming, or the evidence indicated common mortuary practices. Regardless of speculation, all Anasazi risk being painted with broad strokes of over-generalization; some might draw the conclusion that all Anasazi were cannibals, extremely brutal, and fed on a steady diet of man-flesh; that it was a way of life that vanished by the 1300s when their civilization dissolved. But that's not fair.

Ancient human excrement, or coprolite, discovered near a charnel heap, provided the missing link that proved humans ate humans. After rigorous testing it was determined that the coprolite contained the human protein myoglobin, which is only found in heart muscle and skeletal muscle, and which can only enter the intestines if eaten. Myoglobin was also discovered on the inside of a cooking pot. It should be the final nail in the skeptics' coffin.

Despite this proof, many critics were outraged and attempted to explain away these findings. Some went so far as to claim there never were such things as cannibals, anywhere, ever. Others argue these were isolated incidents. Perhaps those eaten were deserving witches, or sworn enemies who had it coming, or the evidence indicated common mortuary practices. Regardless of speculation, all Anasazi risk being painted with broad strokes of over-generalization; some might draw the conclusion that all Anasazi were cannibals, extremely brutal, and fed on a steady diet of man-flesh; that it was a way of life that vanished by the 1300s when their civilization dissolved. But that's not fair.

It's understandable why today's descendants of the Anasazi, the Hopi, Zuni and other pueblo peoples, are dismayed by the very thought of mild-mannered farmers committing such heinous sins. Realistically, though, it's within the realm of human possibility. Humans commit the unthinkable, and no civilization is exempt. Dachau, Pol Pot's Cambodia, Rwanda ... the list over the ages is endless. Even God's chosen people, the ancient Hebrews, sacrificed their children in the fire to the false god Moloch. And when the Babylonian Empire laid siege to Jerusalem in 586/87 B.C., the city’s inhabitants boiled and ate their own children in desperation. People do things.

Questions remain: Did the Anasazi routinely cannibalize each other, neighbor on neighbor? Were they simply starving to death and consequently turned on each other? The sheer brutality of the sacrifices, the clubbing and smashing, suggests not. Turner proposed another alternative. He thinks it's possible a band of Toltecs from Mexico (800 – 1100) became the ruling elite over the Anasazi by sheer force and terror, employing cannibalism and human sacrifice to maintain their tyrannical grip on power for years. And when the Anasazi got tired of it, they revolted and/or ran off.

It's understandable why today's descendants of the Anasazi, the Hopi, Zuni and other pueblo peoples, are dismayed by the very thought of mild-mannered farmers committing such heinous sins. Realistically, though, it's within the realm of human possibility. Humans commit the unthinkable, and no civilization is exempt. Dachau, Pol Pot's Cambodia, Rwanda ... the list over the ages is endless. Even God's chosen people, the ancient Hebrews, sacrificed their children in the fire to the false god Moloch. And when the Babylonian Empire laid siege to Jerusalem in 586/87 B.C., the city’s inhabitants boiled and ate their own children in desperation. People do things.

Questions remain: Did the Anasazi routinely cannibalize each other, neighbor on neighbor? Were they simply starving to death and consequently turned on each other? The sheer brutality of the sacrifices, the clubbing and smashing, suggests not. Turner proposed another alternative. He thinks it's possible a band of Toltecs from Mexico (800 – 1100) became the ruling elite over the Anasazi by sheer force and terror, employing cannibalism and human sacrifice to maintain their tyrannical grip on power for years. And when the Anasazi got tired of it, they revolted and/or ran off.

The idea is not all that far-fetched given the fact that human sacrifice and cannibalism were practiced throughout the jungles of Central Mexico, and the deserts of northern Mexico, and the Caribbean. The American Southwest is just not that far away; extensive trade between the Anasazi and civilizations along the Gulf Coast, and the steamy jungles of Southern Mexico, is archaeologically attested to.

Seemingly frozen in time, conditions at Chaco don't fit many traditional abandonment theories. Archeologists discovered sandals hanging on pegs, lots of painted pottery left behind, corn in granaries, stuff laying around, like turquoise and pendants, that presumably would have been taken if they had gradually moved on with premeditation. If drought, plague or famine pressured them into leaving, wouldn't they have relocated with more of their things? Throughout the Southwest, and particularly at Chaco, it's as though the Anasazi fell into a zombie-trance, pushed away from the table, and walked out the front door.

The idea is not all that far-fetched given the fact that human sacrifice and cannibalism were practiced throughout the jungles of Central Mexico, and the deserts of northern Mexico, and the Caribbean. The American Southwest is just not that far away; extensive trade between the Anasazi and civilizations along the Gulf Coast, and the steamy jungles of Southern Mexico, is archaeologically attested to.

Seemingly frozen in time, conditions at Chaco don't fit many traditional abandonment theories. Archeologists discovered sandals hanging on pegs, lots of painted pottery left behind, corn in granaries, stuff laying around, like turquoise and pendants, that presumably would have been taken if they had gradually moved on with premeditation. If drought, plague or famine pressured them into leaving, wouldn't they have relocated with more of their things? Throughout the Southwest, and particularly at Chaco, it's as though the Anasazi fell into a zombie-trance, pushed away from the table, and walked out the front door.

But even that scenario is unworthy of the silver screen. In my version of events, in a time when the 12th-century Toltec civilization of southern Mexico was waning, Toltec warriors invaded the fabled north-lands bent on conquest and mayhem. Following ancient trade routes, then fanning out across New Mexico's San Juan Basin, the hungry hordes with a taste for human flesh made for Chaco Canyon which they had heard so much about. Once they reached the Southwest the drought was in full swing, food sources were depleted, and the only thing left to eat were the Anasazi.

As the wave of horror rolled across the high desert, the Anasazi fled before them, not walking away, but running for their lives, leaving everything behind; sandals on pegs, pendants and turquoise and all of that wonderful pottery. Stories of brutality and bloody feasts of roasted brains and grilled quadriceps began as rumor largely unheeded, until the telling simply could not be ignored.

But even that scenario is unworthy of the silver screen. In my version of events, in a time when the 12th-century Toltec civilization of southern Mexico was waning, Toltec warriors invaded the fabled north-lands bent on conquest and mayhem. Following ancient trade routes, then fanning out across New Mexico's San Juan Basin, the hungry hordes with a taste for human flesh made for Chaco Canyon which they had heard so much about. Once they reached the Southwest the drought was in full swing, food sources were depleted, and the only thing left to eat were the Anasazi.

As the wave of horror rolled across the high desert, the Anasazi fled before them, not walking away, but running for their lives, leaving everything behind; sandals on pegs, pendants and turquoise and all of that wonderful pottery. Stories of brutality and bloody feasts of roasted brains and grilled quadriceps began as rumor largely unheeded, until the telling simply could not be ignored.

From Chaco Canyon and regions all around, the swifter, more prudent Anasazi relocated to distant, remote canyons, well-hidden mesas, and there they remained among the juniper and pinion pine trees near more dependable water sources, way up high on the sides of towering cliffs where they dwelt in homes easily defended; all they had to do was pull up the ladder.

As for the advancing Toltec, after the last of the locals were tenderized and devoured, or run off, there was no reason to stay, nothing left to eat. All the land was a dust bowl, and there remained no one to rule over and oppress. So gradually, with bellies filled and curiosity about the land up north satisfied, the Toltec, picking the Anasazi out of their teeth, melted back to southern Mexico and the land of pineapples and scarlet Macaws, and old Yellow Beard.

But not before they took the big prize, the famed metropolis at Chaco Canyon, and particularly the Great House called Pueblo Bonito; everyone had heard of Pueblo Bonito. Exercising stealth, the demonic-looking Toltec warriors decorated in facial paint, and wearing strands of human teeth draped around their necks, swarmed over the low walls and climbed over the high walls, ran across the plaza and dropped down into sunken, round kivas, clubbing and crushing and cutting as they went.

Lighting the dark way with burning torches in one hand, and forks in the other, a group of twenty crept down the maze of narrow hallways in single file, going door to door, room to room. And then they stopped at 318-B and knocked politely. No one answered. They knocked again.

Jane and Joe froze in mid-argument. It was probably just the neighbor wanting to borrow another cup of pinion nuts. Slightly peeved at being interrupted, Jane stomped over to the door, got up on her tipi-toes and peeked through the peep-hole. Then she stopped breathing. In a panic she spun around, threw her back against the door and blurted to her husband: "It's for you."

From Chaco Canyon and regions all around, the swifter, more prudent Anasazi relocated to distant, remote canyons, well-hidden mesas, and there they remained among the juniper and pinion pine trees near more dependable water sources, way up high on the sides of towering cliffs where they dwelt in homes easily defended; all they had to do was pull up the ladder.

As for the advancing Toltec, after the last of the locals were tenderized and devoured, or run off, there was no reason to stay, nothing left to eat. All the land was a dust bowl, and there remained no one to rule over and oppress. So gradually, with bellies filled and curiosity about the land up north satisfied, the Toltec, picking the Anasazi out of their teeth, melted back to southern Mexico and the land of pineapples and scarlet Macaws, and old Yellow Beard.

But not before they took the big prize, the famed metropolis at Chaco Canyon, and particularly the Great House called Pueblo Bonito; everyone had heard of Pueblo Bonito. Exercising stealth, the demonic-looking Toltec warriors decorated in facial paint, and wearing strands of human teeth draped around their necks, swarmed over the low walls and climbed over the high walls, ran across the plaza and dropped down into sunken, round kivas, clubbing and crushing and cutting as they went.

Lighting the dark way with burning torches in one hand, and forks in the other, a group of twenty crept down the maze of narrow hallways in single file, going door to door, room to room. And then they stopped at 318-B and knocked politely. No one answered. They knocked again.

Jane and Joe froze in mid-argument. It was probably just the neighbor wanting to borrow another cup of pinion nuts. Slightly peeved at being interrupted, Jane stomped over to the door, got up on her tipi-toes and peeked through the peep-hole. Then she stopped breathing. In a panic she spun around, threw her back against the door and blurted to her husband: "It's for you."

View Comments

John Treadwell Dunbar is a freelance writer