President Obama’s decision to delay implementation of the so-called employer mandate has caused a great deal of discussion among the punditocracy and talking heads.

One thing I haven’t heard discussed is the underlying economic logic of employers providing health insurance at all. Note, it is health insurance, not health care, regardless of the way the administration might prefer to describe it. Health care is provided by doctors and hospitals. General Motors provides health insurance to help employees pay for that health care. And every person in the nation, without exception, has access to health care, again ignoring the verbal virtuosity of the administration telling all of us that denying free contraceptives is denying women access to health care. The fact that anyone of the female persuasion can now purchase the Plan B “morning after” pill without even having to visit a doctor makes a mockery of that claim.

The pundits also tend to talk about employer provided health insurance as if providing such a benefit is a given, a fixture in the economy, something that has been in place since the Declaration of Independence was signed, if not earlier. The fact, though, is that health insurance came into existence during World War II.

During WWII, the Roosevelt administration had imposed wage controls, but offering employer paid health insurance was not considered “wages”. It became the only way that employers could persuade desperately needed workers to change jobs without being able to offer them an increase in salary. With so many men having gone off to the Pacific or European theatres to fight, labor shortages were a chronic problem during the war. Don’t believe it? Then perhaps you could offer another explanation why “Rosie the Riveter” posters are iconic.

Providing health insurance became a popular fringe benefit that did not end when the war ended.

Veterans who had health care provided for them while they were in the military (or in civilian terms, their employer) viewed that as a normal state of affairs. The expectation of a continuance of health care that was paid for at someone else’s expense might have seemed reasonable, even while millions of returning veterans were looking for any job at all in the post-war economy.

For employers, wages are only a part of the cost of having an employee. Wages don’t usually reflect the cost of associated fringe benefits, like paid vacations, paid holidays, the cost of Workers Compensation insurance, the cost of contributions to the various state unemployment funds, or more significantly, the cost of the employer’s share of social security “contributions” and other incidental costs.

So total “wages” for an employee is more than just the number that appears on a paycheck stub. Total wages can be paid in cash, or a mix of cash and fringe benefits. What is overlooked, for very large firms, is that offering more fringes and less cash is actually a financial benefit to the employer.

Fringe benefits that employers provide for their employees are not generally taxed. That’s good for the employee and generally infuriates the IRS. But offering fringes over and above cash to employees provides certain financial and tax benefits for employers which aren’t always that obvious.

For example, I think everyone is aware that employers have to match the amount deducted from your paycheck for social security. There is no social security tax on fringes. Net gain for the employer.

Many legislatively mandated costs, such as worker’s compensation insurance, are calculated as a percentage of the total wages paid by a firm to its employees. Fringe benefits aren’t included in that calculation. Again, a net benefit for the employer. When a firm offers better than average fringe benefits, salaries that they offer might be reduced by a few percentage points, and most employees instinctively make the subconscious cost-benefit analysis that determines that although the cash wage might be slightly less than a competing company might offer, the bundle of fringe benefits makes the entire compensation package worth more. For instance, an extra week of vacation time is effectively a 2% raise.

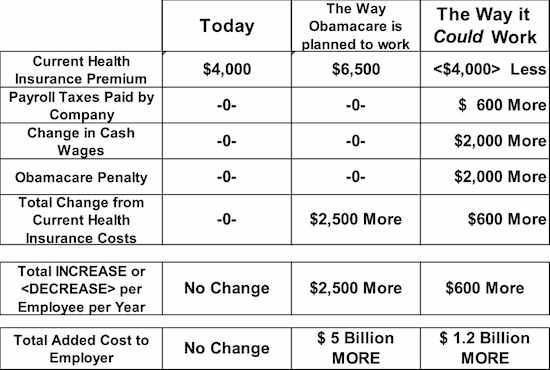

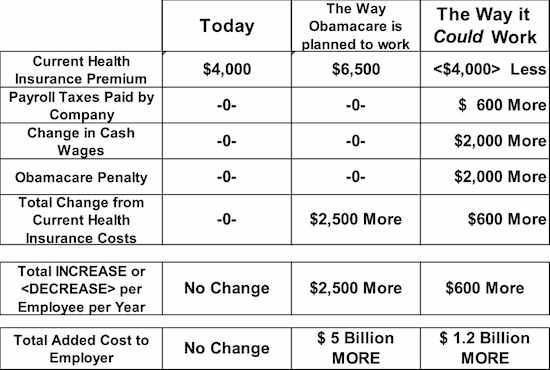

But Obamacare changes the calculus of that exchange. The cost of providing insurance to employees is more than likely going to rise sharply. Let’s just assume, for the sake of argument, that the employer has been paying $4,000 a year for each employee for their health care. Under Obamacare’s mandates, many medical procedures that were not covered before must now be built into the employer provided policies. That will raise costs dramatically. Just to make the math simple, let’s postulate that the average cost of medical insurance per employee would rise to $6,500 or about 62%.

That extra $2,500 per employee per year adds up very quickly. Walmart, for example, has two million employees. If each employee were covered how much would that extra $2,500 per employee cost Walmart? The answer is simple math, and it is FIVE BILLION DOLLARS a year.

As Senator Everett Dirksen is so famously credited with saying, “A billion here, a billion there, pretty soon you’re talking about real money.”

If I were the financial controller for a company like Walmart, I might suggest that the company stop offering any health insurance at all. To soften the blow (and prevent armed insurrection), I would offer the employees a raise in their cash wages equal to the $2,000, or half of what the company is already spending for them on current health insurance costs. The company looks like it isn’t shortchanging the workers, and the total cost of compensation stays the same. The difference goes toward the penalty that Obamacare would levy for not providing health insurance to the company’s employees.

Yes, the company would then be liable for social security taxes, it would see an increase in worker’s compensation insurance and a host of other payroll dependent expense such as unemployment insurance, workers comp insurance and so on, since those expenses are a dependent variable based on total payroll for the firm.

If one assumes that those costs would add 30% to every dollar of the additional $2,000 of wages paid in lieu of providing health insurance, it would amount to $600 per employee plus the $2,000 Obamacare penalty for not providing health insurance, or in other words, there would be an increase in non-health insurance related costs of $600 per year per employee.

The company would, on the other hand, save the cost of the increased premium of $2,500 per employee per year because they wouldn’t be paying anything for health insurance at all. In our example using Walmart, that results in additional costs of $600 per employee per year or to look at the total number, $1.2 billion.

Hmmm? Let’s see, Walmart could spend an extra $5.0 BILLION or only spend $ 1.2 BILLION. What do you think that they would decide? For that matter, what would YOU decide?

While the number of zeros in this example would obviously vary with the size of the company in question, the logic of the analysis would remain the same.

So the passage of Obamacare also indicates the passage of another law – the Law of Unintended Consequences. Obamacare might actually accomplish Barack Obama’s stated goal of fundamentally changing the United States. Perhaps not the way he envisioned it, but it will almost certainly change radically.

Hmmm? Let’s see, Walmart could spend an extra $5.0 BILLION or only spend $ 1.2 BILLION. What do you think that they would decide? For that matter, what would YOU decide?

While the number of zeros in this example would obviously vary with the size of the company in question, the logic of the analysis would remain the same.

So the passage of Obamacare also indicates the passage of another law – the Law of Unintended Consequences. Obamacare might actually accomplish Barack Obama’s stated goal of fundamentally changing the United States. Perhaps not the way he envisioned it, but it will almost certainly change radically.

Hmmm? Let’s see, Walmart could spend an extra $5.0 BILLION or only spend $ 1.2 BILLION. What do you think that they would decide? For that matter, what would YOU decide?

While the number of zeros in this example would obviously vary with the size of the company in question, the logic of the analysis would remain the same.

So the passage of Obamacare also indicates the passage of another law – the Law of Unintended Consequences. Obamacare might actually accomplish Barack Obama’s stated goal of fundamentally changing the United States. Perhaps not the way he envisioned it, but it will almost certainly change radically.