In recent days, we have seen the resurfacing of a seminal moment in Canadian hockey history (and indeed, Canadian history): the 25th anniversary for the trading of National Hockey League (NHL) superstar Wayne Gretzky from the Edmonton Oilers to the Los Angeles Kings in August 1988 by Peter Pocklington.

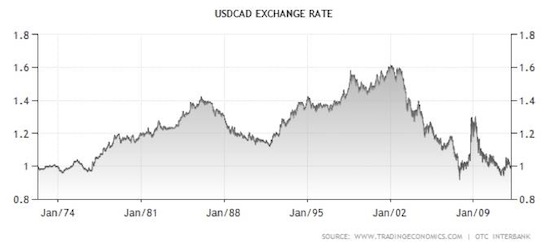

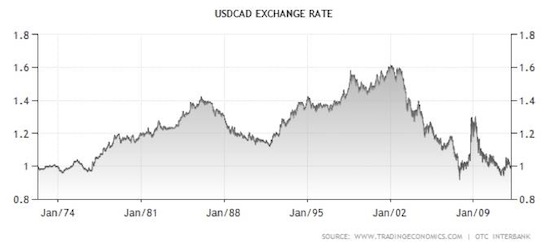

Soon after the Gretzky trade in 1988, hockey began a transition to what could reasonably be considered a far less entertaining style. Because of the ongoing success of superstars such as Gretzky and Mario Lemieux into the mid-1990s as they wound down their careers, the game's offensive and entertainment decline was not abrupt. Pocklington's decision to trade Gretzky in the late 1980s can be construed as rather prescient, since Gretzky was at the peak of marketability, and (as shown in the figure below) within five years after the trade, the Canadian dollar had begun a long steady weakening against the US dollar. This fact placed severe financial strains on several Canadian NHL teams because many of their salaries and expenses were in US currency. Indeed, the period between the mid-1990s and the early 2000s saw the weakest sustained Canadian dollar against its US currency counterpart over the past four decades.

NHL salaries, particularly for superstars, and the related total team salaries also began to skyrocket in the late 1980s and early 1990s. For example, the payroll of the Edmonton Oilers rose from US$8.5 million in 1992-1993 to US$30.9 million in 2002-2003. Other Canadian teams saw similar increases in their payrolls over this period:

- Calgary Flames: US$8.8 million (1992-1993) to US$35.2 million (2003-2004)

- Montreal Canadiens: US$10.3 million (1992-1993) to US$48.6 million (2002-2003)

- Ottawa Senators: US$4.5 million (1992-1993) to US$39.6 million (2003-2004)

- Quebec Nordiques (Colorado Avalanche): US$8.1 million (1992-1993) to US60.1 million (2002-2003)

- Toronto Maple Leafs: US$9.2 million (1992-1993) to US$61.8 million (2003-2004)

- Vancouver Canucks: US$8.8 million (1992-1993) to US$38.7 million (2003-2004)

- Winnipeg Jets (Phoenix Coyotes): US$9.2 million (1992-1993) to US$44.3 million (2002-2003)

The average team salary increased from US$10 million in 1992-1993 to US$44 million in 2003-2004. Gretzky's salary increased from US$1.7 million per season in 1989-1990 to US$6.5 million in 1994-1995. When coupled to the corresponding large decline in value of the Canadian currency, the individual and collective payroll increases over this decade were massive. In retrospect, one could argue Pocklington made a sound business decision in making the Gretzky trade how and when it occurred. Financing a team of superstars like the Edmonton Oilers had during the 1980s within a time of exponentially increasing salaries and an unfavorably declining currency exchange rate as occurred throughout the 1990s, all in a small market such as Edmonton, would have been impossible.

For those that came of age watching the NHL hockey of the 1980s, the current style of the game is purely unsatisfying -- and has been so since the early 1990s. The 1980s marked the "freewheeling" era of professional hockey, with an emphasis on skill, finesse, and offence, and less of the mediocrity that is often celebrated today. But perhaps most importantly, it was the era of the dynasties (the New York Islanders and Edmonton Oilers -- which collectively won 9 of the 11 Stanley Cups between 1980 and 1990), the success of Canadian teams (at least one Canadian team appeared in the Stanley Cup final in each of the years between 1982 and 1990 -- capturing the championship for the entire period of 1984 through 1990), and the individual superstars.

Gretzky was the ultimate superstar, and the list and nature of his records is unparalleled in sports. He is arguably the most dominant player in any sport. But it wasn't just the number of Gretzky's records that made him exceptional; it was the manner in which he obtained them and dominated the sport. Gretzky didn't just establish a new record, he often eclipsed the old record (as with the astonishing 50 goals in 39 games), and then continued at this exceedingly high level of achievement for more than a decade. While Gretzky was the ultimate NHL superstar during the 1980s (and of all-time), he wasn't alone. We also saw several of Gretzky's teammates on the Edmonton Oilers also qualify as superstars (e.g., Messier, Coffey), as well as those on other teams being able to claim ultra top-tier status (of which Lemieux was probably the best example).

By the mid-1990s, it was clear the game had changed, and was continuing to change, and -- to those that loved the 1980s style of hockey -- it was not for the better. Compared to the 1980s, the style of NHL hockey over the past 15 years or so can best be classified as the "watching grass grow" era, where -- instead of marvelling at pure unrestricted talent with hockey games (even during the regular season) that kept one on the edge of the seat from start-to-finish -- we are now resigned into trying to justify a growing appreciation for "the trap", defensive prowess, bodychecks, strong goaltending, and skills such as "cycling the puck" (which, unfortunately, leads too often to a lot of cycling and not enough shooting and scoring).

But do the statistics back up this type of subjective analysis? Yes.

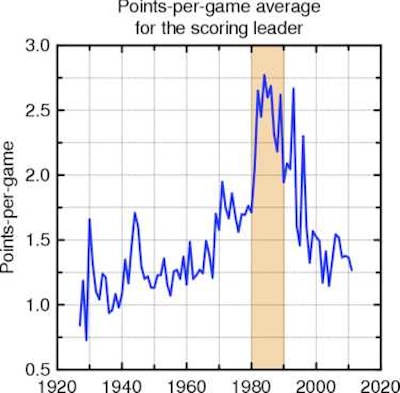

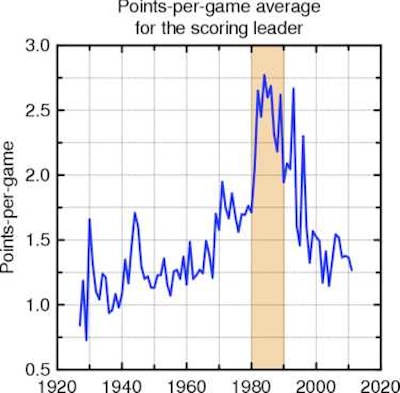

We can start with the number of regular season points-per-game the point scoring leader in each season has obtained. Total number of points by the scoring leader is not a useful metric, since the number of games played has increased dramatically since the 1920s (from 44 games in 1927 up to the current 82 game schedule). One could argue that points-per-game by the scoring leader is not the best metric, since it may overlook a player who did not lead the scoring race but who scored more points-per-game than the scoring leader did. Since the regular season of hockey is long and grueling, stamina matters when assessing excellence. We also have no idea how many points-per-game the player who did not lead the scoring race would have achieved had he played as many games as the scoring leader. Thus, for the present analysis, we'll restrict ourselves to the points leaders of each year.

Regular season points-per-game by the point scoring leader increased slightly up to the 1970s, after which a modest increase was held throughout this decade, but the real jump came during the Gretzky-era in the 1980s -- and ended with the end of the Gretzky-era in the late 1990s.

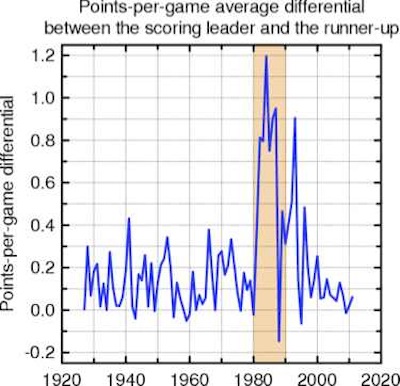

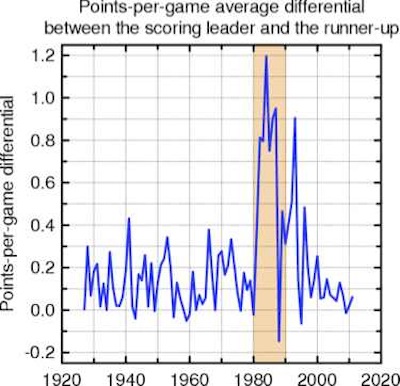

But scoring was generally higher across-the-board during the 1980s, so perhaps this period just represents a time during which everyone scored more, but there was no change in the differentiation between the top-tier and second-tier scorers? Such is not the case. If we look at the regular season points-per-game differential between the scoring leader in each season and the second-place scorer, we see further evidence of 1980s exceptionalism, and the era of the true superstar (i.e., a player that truly dominates his competition).

For those wondering how the points-per-game differential can be negative, these represent seasons where the second-place scorer had a higher points-per-game average than the scoring leader. A good example is the 1987-1988 season, where Lemieux scored 168 points in 77 games (2.18 points-per-game) and led the league in total points, while Gretzky finished second in scoring with 149 points in 64 games (2.33 points-per-game). This plot makes the ultimate case for the Gretzky-era of superstardom. The leader-to-runner-up regular season points-per-game differential for the two top scorers in each season was approximately constant from the 1920s up to the arrival of Gretzky, was elevated (by up to an order-of-magnitude if one takes the pre-1980 average differential as comparison) throughout the Gretzky era, and then returned to the historically low range for the post-Gretzky era up to the present. Yes, scoring was generally up during the 1980s, but it was a time when the best was more clearly the best than at any other point in NHL history. This was the superior entertainment value of 1980s NHL hockey. Parity is a form of mediocrity, even if it is at a relatively high level. Fans love individual superstars with staying power (i.e., not the one-hit wonders) and team dynasties. The 1980s NHL had both.

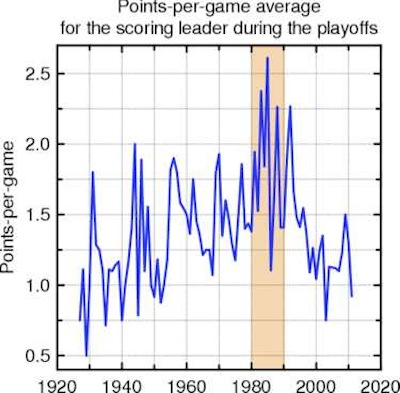

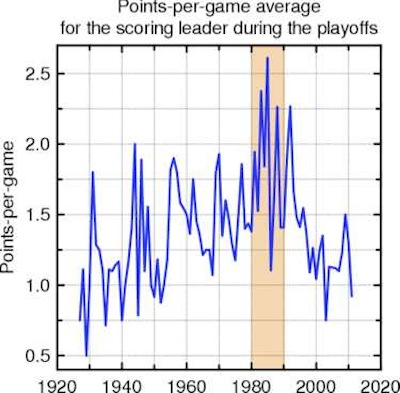

Playoff scoring and superstar-based entertainment was also at historic highs during the 1980s. If we look at the point-per-game average by the playoff scoring leader, we see that -- once again -- the 1980s are the peak, and following the end of the Gretzky-era, a return to the historical lows (and boring playoff hockey).

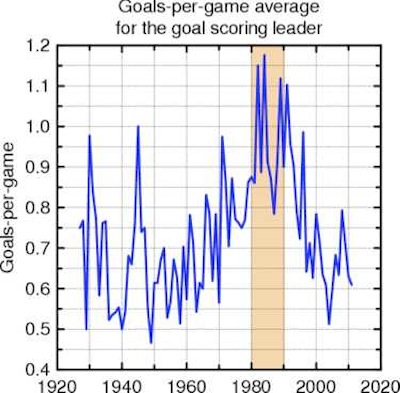

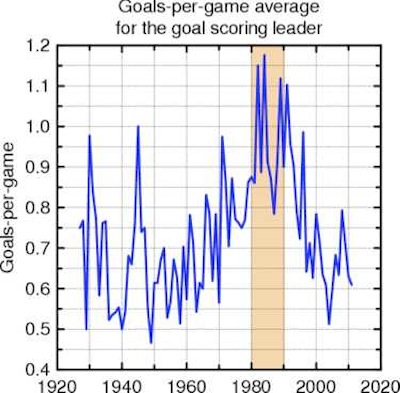

Goals-per-game for the goal scoring leader in each season increased steadily starting in the early 1960s, reached their peak during the Gretzky era (of which Gretzky, of course, holds the single-season, all-time, and many other goal scoring records), and has since declined back to historical lows in the post-Gretzky era.

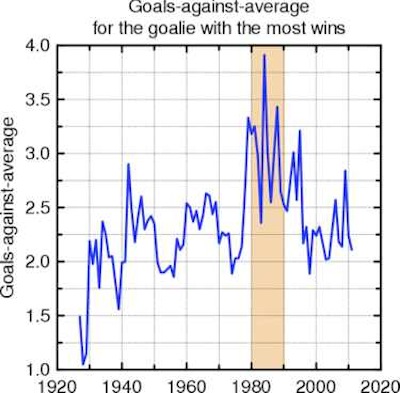

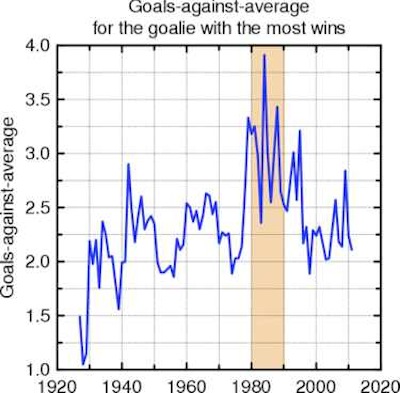

The increased scoring in the Gretzky-era also corresponds with a historically elevated goals-against-average for the goalie with the most wins in each season.

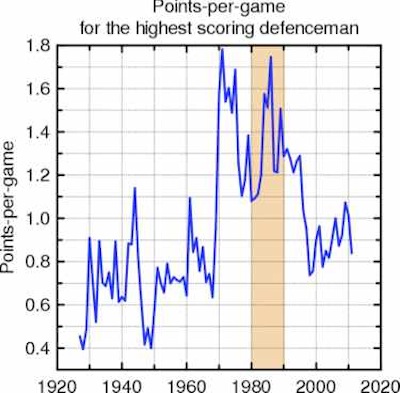

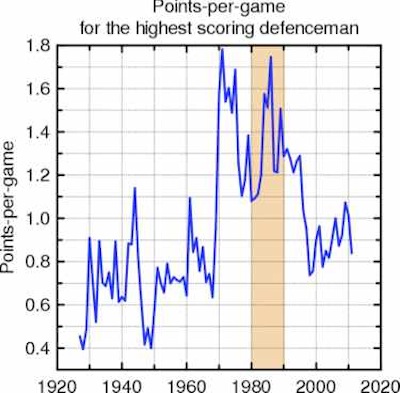

The 1980s also saw the era of the high-scoring defenceman continue (e.g., Coffey), building on the pioneering offensive capabilities of Bobby Orr -- who largely conceived the concept of a high-scoring defenceman when he burst into the league in late 1960s and achieved scoring prominence in the early-- through mid-1970s.

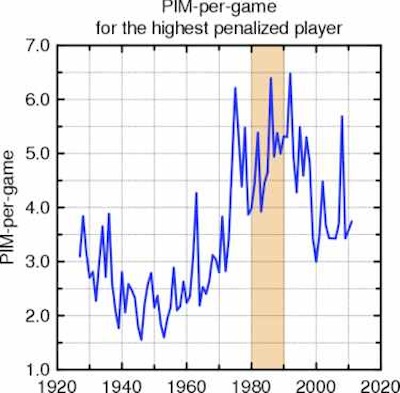

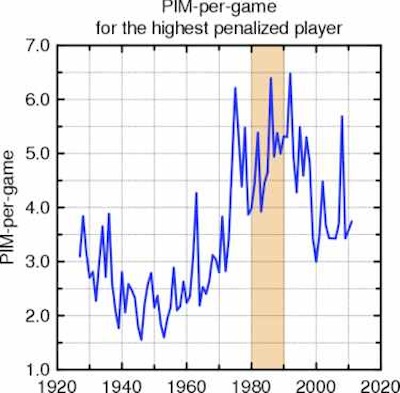

High scoring wasn't the only part of the 1980s hockey entertainment mix. There were a lot of penalties, and the behavior that led to the penalties was often more entertaining than we have in the current "cowardly thug" era. The 1980s saw a number of well-known (and regular) team brawls that were as enjoyable to watch as the scoring. If we look at the regular season penalties-in-minutes (PIM) for the highest penalized player of each year, we see more exceptionalism. Starting in the mid-1970s through to the mid- to late-1990s, the most penalized players were much more penalized on average than they were either prior to or after this timeframe. Lots of goals, lots of penalties (particularly fighting and brawls) = lots of excitement.

Efforts have been underway since the mid-1990s into making the game more exciting, as many current fans can remember the entertainment superiority of the Gretzky-era in general, and 1980s in particular. Unfortunately, the statistics shown here illustrate two key points: (1) the Gretzky era was unique and exceptional, but it clearly built on previous decades working towards the more entertaining style; and (2) the dominant history of the game is lower scoring and less penalized. This does not bode well for the future of hockey (at least to those that found the peak entertainment value during the 1980s). The style of the game cannot be rapidly changed, and its equilibrium state is effectively the current style.

Perhaps another Gretzky-era will rise again, but if so, it would be another historical anomaly and would likely take decades to build towards achieving. That class of hockey players cannot be constructed overnight. There is also a much different culture now in hockey (and in society) than there was in the 1980s: in the 1980s, it was often frowned upon to be a less-talented individual that brings down a more talented one, and this was a positive feedback for success and generating superstars; in today's politically correct world, it is often un-cool to positively celebrate the more talented, and thus we see a negative feedback against rising superstars. Today's hockey players have neither the physical nor mental capacity to play 1980s style hockey.