On March 18, 2014, the Knesset passed the Governance Law, raising the electoral threshold from 2 to 3.25 percent.

All the coalition factions joined together to pass the law by a majority of 67 MKs. All the opposition factions opposed it, including the Arab parties, which argued that it would make it difficult for them to be elected to the Knesset in the future. The question now is, will the law prevent the Arab parties from reaching the electoral threshold and thereby preclude their representation in the forthcoming Knesset? Or, will the law prompt the Arab parties to join forces, which would thereby increase the number of Arab MKs? However, in order for the Arab parties to unite, a new political leadership is needed that has both the power to lead and outline its vision and the ability to address the needs of the Arab street.

On March 18, 2014, the Knesset passed the Governance Law, raising the electoral threshold from 2 to 3.25 percent. All the coalition factions joined together to pass the law by a majority of 67 MKs. All the opposition factions opposed it, including the Arab parties, which argued that it would make it difficult for them to be elected to the Knesset in the future.

Three Arabs served in the first Knesset in 1949, two of them from the Democratic List of Nazareth, established by Mapai, and one from the Communist Party. Since then, every Knesset has included Israeli Arabs, either from independent Arab parties or from Jewish parties. The question now is, will the law prevent the Arab parties from reaching the electoral threshold and thereby preclude their representation in the forthcoming Knesset? Or, will the law prompt the Arab parties to join forces, which would thereby increase the number of Arab MKs? Is there a chance that the three main parties, with all their ideological differences - Balad, with its liberal nationalist ideology; Ra’am-Ta’al, with its Muslim ideology; and Communist Hadash, which is a Jewish-Arab party - will succeed in uniting?

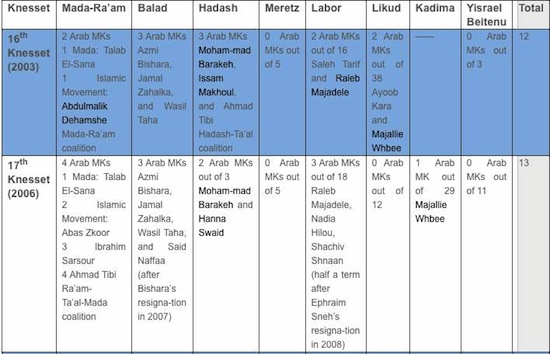

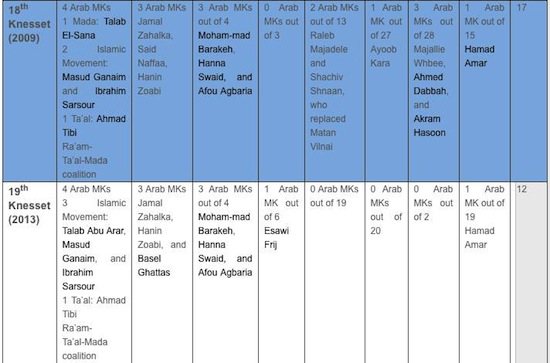

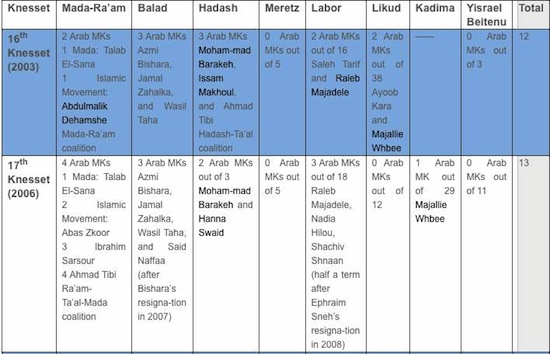

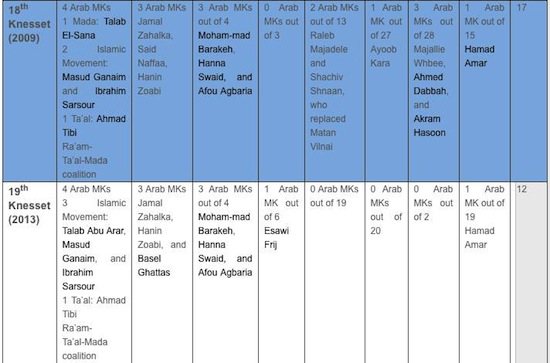

In each of the past three Knesset elections, the Ra’am-Ta’al bloc won four seats. If it continues to exist in the future, it has the best chance to pass the new electoral threshold. Hadash has had four seats in the last two elections (three Arab MKs and one Jewish). Based on the results of the last election, it is now on the border of the electoral threshold, and thus in order to ensure a place in the twentieth Knesset, must increase its political strength or join another bloc or party. For its part, Balad, which now has three seats, is unlikely to succeed in passing the new threshold on its own (table 1). Note that in the most recent local elections, all the Arab parties lost strength. Hadash lost the mayoralty in thirteen Arab towns, Balad’s influence declined, and the Islamic Movement decided not to run in the municipal elections.

Accordingly, the Arab parties face two principal scenarios. In the pessimistic scenario, all the Arab parties will run independently in the next elections, and consequently will likely remain outside of the Knesset. Perhaps one or two Arab or Druze MKs will succeed in being elected from a Jewish party. In the optimistic scenario, the Arab parties will unite in one way or another, and together they will increase voter turnout among Israeli Arabs (from 50 percent to 70 percent). As a result, the number of Arab MKs will increase from fifteen to seventeen or even more. Indeed, a position paper submitted in 2013 by Asad Ghanem, Nohad Ali, and Sammy Smooha to the Knesset Constitution, Law, and Justice Committee argued that not only would raising the electoral threshold not hurt Arab representation in the Knesset, it could actually increase it.

A poll conducted by the Abraham Fund showed that voter turnout could rise if the Arab parties joined together. The percentage of undecided Arab voters was estimated at some 32 percent, a significant finding given that the percentage of actual voters in the last election was some 56 percent of eligible voters, with some 77 percent voting for Arab parties and 22.8 percent for Jewish parties. Similarly, in a poll conducted by Sammy Smooha prior to the 2013 elections, 76 percent of Israeli Arabs wanted the Arab parties to unite and some 28 percent of the respondents stated that they would not vote for any Arab party if the parties did not unite.

Although chances in the past that the Arab parties would combine forces appeared minimal, given the conflicts between and within parties, the default choice that the Governance Law presents to the Arab parties is unification. If so, what kind of coalitions could be put together prior to the elections for the twentieth Knesset, and will all the Arab parties join together, or only some of them? In the past, ideological differences among the Arab parties did not present an obstacle to mergers and splits and their activities in the Knesset were characterized by similar trends.

The actual political situation is straddling the two scenarios mentioned above, and against the backdrop of the social and economic hardships of Israeli Arabs, the leaders of the Arab political parties have not succeeded in formulating a unified position on an appropriate response to the new challenge. In the last Knesset elections, the Arab parties did not feature any new candidates. Yet as a result of social changes among Israeli Arabs, there is a trend toward the weakening of the traditional political leadership and a rise in the power of two marginalized groups in Arab society: young people and women.

In the recent elections in Nazareth, the largest Arab city in Israel, Balad and the Islamic Movement joined with a local leadership bloc to work against Hadash. As a result, for the first time in twenty years, Hadash lost the mayoral elections. If this is an indication of a future national trend, then despite their ideological differences the liberal-nationalist Balad and the Islamic Movement might unite or merge in the next elections and run together against Hadash. The estrangement between Balad and Hadash can also be seen in Jaffa, where, after Balad and Hadash ran jointly in the Tel Aviv-Jaffa municipal elections for twenty years, no Arab representative was elected. In the previous elections, the Mada list, headed by former MK Talab El-Sana, did not pass the electoral threshold, even though in the eighteenth Knesset, it ran for election with Ta’al, and there is a reasonable chance that in the next elections, it will attempt to unite with one of the blocs.

In the future, then, there will likely be two political factions at most, as there is no room for more, and Israeli Arabs will expect that these factions will cooperate with each other. Today’s leadership has used up its quota of the Arab public’s trust, and new leadership is necessary to spearhead mergers and unification among the existing parties and factions. This means that there is the potential for new groups to arise, including young people and women, and that new faces may be presented to the Arab voter.

Although given these scenarios, Hadash will have a significant challenge in the coming period, it is unlikely that Hadash will turn to non-Arab left wing parties if it fails to find what it seeks among the Arab parties, given its Communist ideology, singular among Israeli parties. A related question is whether, if there is no overall unification among the Arab parties, the Jewish parties will increase their activity among Israeli Arabs in order to receive the votes of Arabs who are concerned about their lack of influence over their situation in the country.

In conclusion, in order for the Arab parties to unite, a new political leadership is needed that has both the power to lead and outline its vision and the ability to address the needs of the Arab street. The longstanding conflicts and competition among the Arab parties, as well as the history of mutual recrimination among their leaders, are obstacles to their joining forces. In order for this theoretical scenario to occur, the Arab parties will have to rise above their differences, increase their attractiveness in the eyes of the Arab public, and present Arab voters with new candidates for the Knesset.

Table 1. Arab MKs and their Parties, 2003-2013