By Sierra Rayne ——Bio and Archives--April 30, 2014

Global Warming-Energy-Environment | CFP Comments | Reader Friendly | Subscribe | Email Us

"In North America, there is good evidence of northward expansion of the distribution of the tick vector (Ixodes scapularis) in the period 1996-2004 based on an analysis of active and passive surveillance data. However, there is no evidence so far of any associated changes in the distribution in North America of human cases of tick-borne diseases ... The complex ecology of tick-borne diseases such as Lyme disease and TBE [tick-borne encephalitis] make it difficult to attribute particular changes in disease frequency and distribution to specific environmental factors such as climate ... Substantial warming in higher-latitude regions will open up new terrain for some infectious diseases that are limited at present by low temperature boundaries, as already evidenced by the northward extensions in Canada and Scandinavia of tick populations, the vectors for Lyme disease and tick-borne encephalitis."Earlier reporting by the IPCC came to the following conclusions:

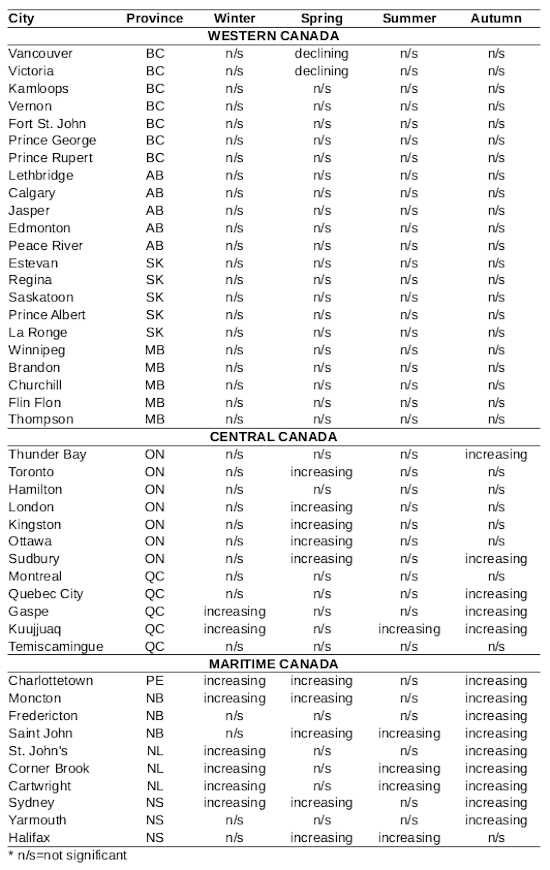

"The transmission cycle of Lyme disease involves a range of mammalian and avian species, as well as tick species -- all of which are affected by local ecology. Under climate change, a shift toward milder winter temperatures may enable expansion of the range of Lyme disease into higher latitudes and altitudes, but only if all of the vertebrate host species required by the tick vector also are able to expand their distribution. A combination of milder winters and extended spring and autumn seasons would be expected to prolong seasons for tick activity and enhance endemicity."Barton's article goes on to state that "disease-carrying ticks in Canada have increased tenfold in the past two decades, spread by migratory birds and nurtured by warming climates that allow them to thrive in our own backyards." The problem here is that not all of Canada has been warming over the past two decades, and we need to keep that in mind when assessing the possible impacts of climate change on lyme disease. Indeed, the entire western half of the nation has not warmed in any season during the last 20 years. The following table shows statistically significant (p<0.05) changes in seasonal temperatures between 1992 and 2012 (the latest year available in the Environment Canada Adjusted and Homogenized Canadian Climate Database) by city across Canada. All of the warming is located in Central Canada (Ontario and Quebec) and the Maritime provinces.

For scale comparison, the four Western Canada provinces have an area of 2,905,000 km2, whereas the six Central and Maritime Canada provinces make up only slightly more at 3,157,000 km2.

Lyme disease is an important public health issue, and the number of cases being reported each year in Canada is increasing, although how much of this increase is due to more vigilant reporting versus actual increased occurrence remains unknown.

But that isn't the issue at hand. The concerns involve stating generally that Canada has been warming over the past two decades -- when it hasn't (the warming is localized in the eastern half of the country) -- as well as employing climate models to project the distribution of Lyme disease vectors, particularly for western Canada. There is very poor agreement between observed and projected climate trends in western Canada (see, e.g., these three studies), and a fundamental tenet of science is that if your predictive capacity is low, the results should not be employed for subsequent work.

Large numbers of scientific articles are continually being published on the linkages between climate change and disease. In many cases, the predictions are being used to shape public health policies at significant taxpayer expense. And yet, global climate models have not performed well for temperature predictions, with the results for regional and local downscalings even worse. The climate alarmism needs to be kept out of public health policy making, and not just with respect to lyme disease. Once the climate models offer high-quality predictivity at local and regional scales, then apply them to public health issues. But not a moment before that.

For scale comparison, the four Western Canada provinces have an area of 2,905,000 km2, whereas the six Central and Maritime Canada provinces make up only slightly more at 3,157,000 km2.

Lyme disease is an important public health issue, and the number of cases being reported each year in Canada is increasing, although how much of this increase is due to more vigilant reporting versus actual increased occurrence remains unknown.

But that isn't the issue at hand. The concerns involve stating generally that Canada has been warming over the past two decades -- when it hasn't (the warming is localized in the eastern half of the country) -- as well as employing climate models to project the distribution of Lyme disease vectors, particularly for western Canada. There is very poor agreement between observed and projected climate trends in western Canada (see, e.g., these three studies), and a fundamental tenet of science is that if your predictive capacity is low, the results should not be employed for subsequent work.

Large numbers of scientific articles are continually being published on the linkages between climate change and disease. In many cases, the predictions are being used to shape public health policies at significant taxpayer expense. And yet, global climate models have not performed well for temperature predictions, with the results for regional and local downscalings even worse. The climate alarmism needs to be kept out of public health policy making, and not just with respect to lyme disease. Once the climate models offer high-quality predictivity at local and regional scales, then apply them to public health issues. But not a moment before that.View Comments

Sierra Rayne holds a Ph.D. in Chemistry and writes regularly on environment, energy, and national security topics. He can be found on Twitter at @srayne_ca