By Sierra Rayne ——Bio and Archives--July 12, 2014

Global Warming-Energy-Environment | CFP Comments | Reader Friendly | Subscribe | Email Us

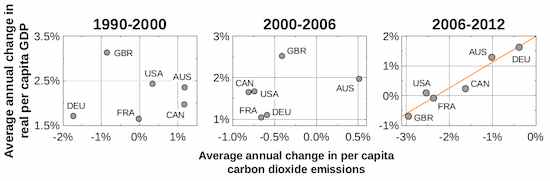

The lack of correlation between changes in carbon dioxide emissions and economic growth during the 1990-2000 and 2000-2006 periods breaks the general causation argument that lower economic growth will result in lower emissions. Conversely, the strong relationship we see between 2006 and 2012 supports the view held by many -- that efforts to purposefully reduce carbon dioxide emissions will harm our economies.

If economic growth -- or a lack thereof -- was a robust, general determinant of carbon dioxide emissions among these developed nations, we would expect to see significant correlations between the variables in all three time periods. But that's not what we find. From 1990 to 2006, when carbon dioxide emissions were changing very little among the nations, economic growth appears to have been largely decoupled from carbon dioxide emission trends. After 2006, once these nations collectively began focusing on emissions reductions through a variety of mechanisms and emissions started to decline substantially, then a clear relationship emerged between emissions and growth rates.

Other factors are also at play in defining growth rates, particularly in the period including and following the global financial crisis. That said, the emergence of this strong correlation -- along with the other region-specific evidence put forward to date in prior articles -- is very suggestive of a linkage between efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and subsequent economic damage.

For these reasons, the UN's claims that these national economies will grow at relatively rapid rates even as they are effectively entirely decarbonized over the span of only a few decades seems implausible given the recent evidence at hand. The developing nations get this already, which is why "India, Brazil, South Africa and China have said they will not agree to any binding cuts in their emissions." Why? Because they recognize severe economic damage will result.

What kind of emissions reductions is the UN report thinking are required?

The lack of correlation between changes in carbon dioxide emissions and economic growth during the 1990-2000 and 2000-2006 periods breaks the general causation argument that lower economic growth will result in lower emissions. Conversely, the strong relationship we see between 2006 and 2012 supports the view held by many -- that efforts to purposefully reduce carbon dioxide emissions will harm our economies.

If economic growth -- or a lack thereof -- was a robust, general determinant of carbon dioxide emissions among these developed nations, we would expect to see significant correlations between the variables in all three time periods. But that's not what we find. From 1990 to 2006, when carbon dioxide emissions were changing very little among the nations, economic growth appears to have been largely decoupled from carbon dioxide emission trends. After 2006, once these nations collectively began focusing on emissions reductions through a variety of mechanisms and emissions started to decline substantially, then a clear relationship emerged between emissions and growth rates.

Other factors are also at play in defining growth rates, particularly in the period including and following the global financial crisis. That said, the emergence of this strong correlation -- along with the other region-specific evidence put forward to date in prior articles -- is very suggestive of a linkage between efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and subsequent economic damage.

For these reasons, the UN's claims that these national economies will grow at relatively rapid rates even as they are effectively entirely decarbonized over the span of only a few decades seems implausible given the recent evidence at hand. The developing nations get this already, which is why "India, Brazil, South Africa and China have said they will not agree to any binding cuts in their emissions." Why? Because they recognize severe economic damage will result.

What kind of emissions reductions is the UN report thinking are required?

"This 2050 level translates to a benchmark of 1.6 tons of CO2-energy emissions per capita by 2050, assuming a global population of 9.5 billion by 2050, in line with the medium fertility projection of the UN Population Division."To get to these levels would require the following percentage reductions from current emissions over the next 35 years: Australia, 91%; Canada, 90%; France, 71%; Germany, 84%; the UK, 79%; and the USA, 91%. Emissions reductions of over 90 percent in just over three decades while maintaining strong economic growth? Not likely, given what we've seen over the past several years in nations that have made concerted efforts to cut emissions even modestly. Unsurprisingly, the UN proposal reads like an exercise in central planning:

"The Country Teams underscore that successful implementation of national DDPs [Deep Decarbonization Pathways] depends on 'directed technological change' -- that is technological change that is propelled through an organized, sustained, and funded effort engaging government, academia, and business with targeted technological outcomes in mind. No Country Research Team was comfortable assuming that their country alone could develop the requisite low-carbon technologies. Likewise, market forces alone will not be sufficient to promote the required RDD&D [research, development, demonstration, and diffusion] at the right scale, timing, and coordination across economies and sectors -- even when these market forces are guided by potential large profits from the generation of new intellectual property. Technological success will therefore require a globally coordinated effort in technology development, built on technology roadmaps for each of the key, pre-commercial low-carbon technologies. Directed technological change should not be conceived as picking winners, but as making sure the market has enough winners to pick from to achieve cost-effective low-carbon outcomes."In sum, we can't rely on the free market, so a group of globalist individuals will choose the most promising technologies -- but remember, we're not picking winners. No, of course not. Actually, picking winners is exactly what the UN is proposing. Who will pick these winners? A group of well-connected, and undoubtedly financially vested, people in "government, academia, and business." Sounds like a perfect recipe for crony capitalism, all on the taxpayer's dime. Of course, this statement from the UN report also cannot go without comment:

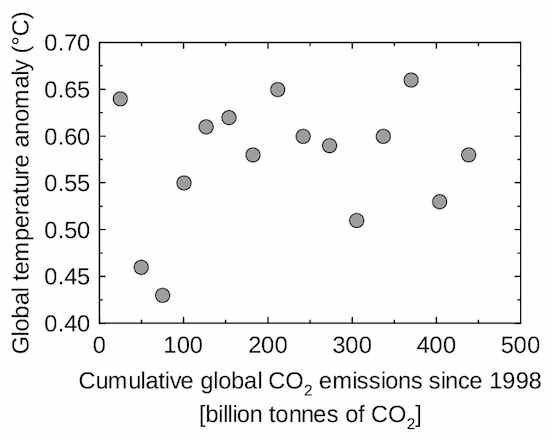

"The overall relation between cumulative GHG emissions and global temperature increase has been determined to be approximately linear."Sure it is. That's why the plot of global temperature versus cumulative global GHG emissions by year since 1998 looks like this.

Well, I guess it is approximately linear. A horizontal line perhaps, with no statistically significant relationship between global carbon dioxide emissions and global temperature since at least 1998.

More of these spin efforts will be attempted as the alarmists try to build an international case for a 2015 Global Climate Accord, but they must be rejected. All the economic and climate policy datasets so far tell a consistent story -- zero carbon is inconsistent with strong and stable economic growth at this point in time.

Well, I guess it is approximately linear. A horizontal line perhaps, with no statistically significant relationship between global carbon dioxide emissions and global temperature since at least 1998.

More of these spin efforts will be attempted as the alarmists try to build an international case for a 2015 Global Climate Accord, but they must be rejected. All the economic and climate policy datasets so far tell a consistent story -- zero carbon is inconsistent with strong and stable economic growth at this point in time.

View Comments

Sierra Rayne holds a Ph.D. in Chemistry and writes regularly on environment, energy, and national security topics. He can be found on Twitter at @srayne_ca