By Sierra Rayne ——Bio and Archives--August 20, 2014

Global Warming-Energy-Environment | CFP Comments | Reader Friendly | Subscribe | Email Us

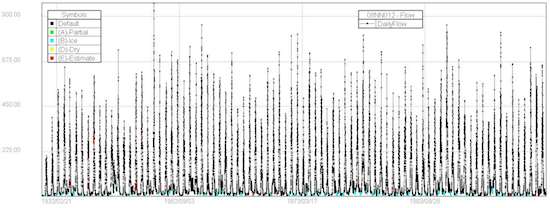

"In the spring of 2007, despite an above average snow pack, the peak in freshet run-off was barely noticeable across the entire Kettle River system. In the view of many locals, this was a clear indication of water extraction pressures and yet, new proposals have continued to come forward. Among these are new withdrawal proposals for large scale condo developments, golf courses and ever expanding land development and settlement."The peak in freshet (spring thaw) run-off was barely noticeable across the entire Kettle River system in 2007? This is an absolutely absurd statement. The following chart, extracted from the Environment Canada Water Survey of Canada database, shows the daily flows on the furthest downstream hydrometric station for the Kettle River (08NN012: Kettle River near Laurier) since records began in 1929.

The freshet peak for 2007 is the seventh peak in from the right side of the chart (i.e., the last peak on the right is for 2013). Barely noticeable? It's not even close to the lowest freshet peak on record (even 2001 and 2004 were lower), and it is orders of magnitude above the winter and summer low-flow periods that border it. Furthermore, there is no significant trend in the magnitude of the freshet peak flow over the historical record. Actually, the correlation is positive towards higher flows, not negative towards lower flows.

None of the other upstream stations in the Kettle River basin have hydrographs supporting the statement that "the peak in freshet run-off was barely noticeable across the entire Kettle River system" in 2007. Such statements are terrible science communication to the public, and yet not a single media outlet covering the story bothered to fact-check this problematic claim.

What about the Vancouver Sun claim that the Kettle River is "so starved of water in summer that some stretches can't even float an inner tube"? There are no significant trends in average June, July, or August flows for the Kettle River at Laurier since records began. And the correlations are positive -- towards increasing average summer flows, not negative.

Yet, the concerns over summer low flows in the Kettle River continue to be repeated. Just last month, Mark Hume wrote an article on the subject in the Globe and Mail, claiming that "when it runs hot and low, as it increasingly does, the Kettle River becomes something of a death trap for rainbow trout. The fish have to retreat to deep pools or they might die when the water heats up to 20 C or more, as it often does during low flows in July and August." Of course, climate change is apparently to blame, as Hume states: "In many ways the Kettle serves as a warning sign of what's to come in British Columbia, as climate change exacerbates problems already created through poor water management."

The only evidence I can find in Hume's article to support this statement is a reference to a discussion paper for the Kettle River Watershed Management Plan that was released in July of this year. The report states that "the Phase 1 Report evaluated hydrometric records for trends in river discharge over time using monthly means. It found no statistically significant trend from 1929-2010, and a slight downward trend from 1981-2010." Interesting, as I find no significant trend in annual flows for the Kettle River at Laurier between 1981 and 2010.

A few months do exhibit declining average flows over the 30-year period between 1981 and 2010, but this claimed finding is of concern because if we choose the more recent 30-year period from 1984 to 2013, those few months with significant declining flows disappear and we end up with absolutely no months showing significant declining flow trends during the last three decades. The 1984 to 2013 annual flow series also doesn't have a significant trend over this time-frame. In fact, the correlation is positive towards increasing flows, not negative.

Details like this are critical. If you choose an analysis period with several low flow years at the end of it and/or high flow years at the start, a regression time series may be skewed to yield a non-robust declining trend that will disappear a few years later. Consequently, great caution must be exercised when making policy decisions based on short time series such as those only 30 years in length which contain unusually low (or high) values on either end.

This discussion paper referenced by the Globe and Mail also claims that "a new analysis of flow data for Laurier, Washington showed a small but meaningful downward trend in the volume of water flowing during three day and seven day low flows for the entire period of record (1929-2012) and from 1980-2012." Using the methods as described in the paper, I was unable to reproduce the results, even after cross-checking the results between the two approaches of (1) analyzing the USGS data for the Kettle River at Laurier with the Nature Conservancy's Indicators of Hydrologic Alteration program (i.e., the approach described in the discussion paper) and (2) obtaining the same data via the Environment Canada Water Survey of Canada database and manually generating the low-flow statistics with a separate spreadsheet.

Quite simply, I do not obtain the same input data for subsequent statistical analyses as is reported in the paper. My statistical tests also differ substantially in the magnitude of any significance/non-significance, but the overall conclusions are similar. Between 1929 and 2012, there is a significant decline in the 3-day minimum flows on the river, and between 1980 and 2012, there are significant declines in both the 3-day and 7-day minimum flows. But, once again, if we include the latest 2013 data, the significance of the post-1980 trends disappears -- showing the statistical conclusions are not robust if the addition of a single year's worth of new data changes the conclusions dramatically from significant to non-significant trends.

And over the past 30 years (i.e., since 1984) -- which is a more common climate science metric -- there has been absolutely no sign of a significant declining trend in either the 3- or 7-day minimum flows.

We cannot make rational policy choices if we are yo-yo-ing between statististical significance/non-significance by adding a year or two to an environmental data set. Overall, I'd like to see the Kettle River Watershed Management Plan re-examine their analyses and confirm (or correct) their already published results, and then update their initial analyses with the 2013 data to see if they reach the same conclusions regarding statistical non-significance as I did. Duplication is the key to good science, and is a must for framing solid water policies.

The more important concern is that the analyses appear to have been performed on the annual flow series, and in this region, the annual 3- and 7-day minimum flows often occur in the wintertime under ice cover. Flows measured during this time are also often unreliable due to ice cover, and can be systematically biased over time due to non-random changes in measuring devices and other factors. The core issue on the Kettle River from Hume's article seems to be the confluence of low flows in mid- to late-summer that lead to high water temperatures, which in turn harms aquatic life such as fish. Low flows in the middle of winter are irrelevant for these types of issues. Thus, we need to focus on the aquatic stressor at issue and isolate the appropriate flow trends accordingly -- ignoring flow trends that are unrelated to the topic at hand.

Consequently, when I reanalyze the Kettle River at Laurier low flow dataset for the 3- and 7-day minimum flows during the more ecologically relevant extended summer season (June through September), I find no significant trend either since records began, or during the last 30 years.

In the backgrounder for the 2011 BC Endangered Rivers list, Angelo goes on to claim that "in the past three summers, the Kettle River has experienced record low flows (so low at times that locals couldn't even tube down parts of the river)." This is another claim I cannot verify, since as best I can tell, none of the years between 2008 and 2011 contained record low flows during the summertime tubing season.

The lack of seemingly rigorous science and objective journalism surrounding water resources in British Columbia is something I've been concerned about for many years, and yet these types of problems continue to fester and expand with the full knowledge and approval of the public sector science establishment.

The freshet peak for 2007 is the seventh peak in from the right side of the chart (i.e., the last peak on the right is for 2013). Barely noticeable? It's not even close to the lowest freshet peak on record (even 2001 and 2004 were lower), and it is orders of magnitude above the winter and summer low-flow periods that border it. Furthermore, there is no significant trend in the magnitude of the freshet peak flow over the historical record. Actually, the correlation is positive towards higher flows, not negative towards lower flows.

None of the other upstream stations in the Kettle River basin have hydrographs supporting the statement that "the peak in freshet run-off was barely noticeable across the entire Kettle River system" in 2007. Such statements are terrible science communication to the public, and yet not a single media outlet covering the story bothered to fact-check this problematic claim.

What about the Vancouver Sun claim that the Kettle River is "so starved of water in summer that some stretches can't even float an inner tube"? There are no significant trends in average June, July, or August flows for the Kettle River at Laurier since records began. And the correlations are positive -- towards increasing average summer flows, not negative.

Yet, the concerns over summer low flows in the Kettle River continue to be repeated. Just last month, Mark Hume wrote an article on the subject in the Globe and Mail, claiming that "when it runs hot and low, as it increasingly does, the Kettle River becomes something of a death trap for rainbow trout. The fish have to retreat to deep pools or they might die when the water heats up to 20 C or more, as it often does during low flows in July and August." Of course, climate change is apparently to blame, as Hume states: "In many ways the Kettle serves as a warning sign of what's to come in British Columbia, as climate change exacerbates problems already created through poor water management."

The only evidence I can find in Hume's article to support this statement is a reference to a discussion paper for the Kettle River Watershed Management Plan that was released in July of this year. The report states that "the Phase 1 Report evaluated hydrometric records for trends in river discharge over time using monthly means. It found no statistically significant trend from 1929-2010, and a slight downward trend from 1981-2010." Interesting, as I find no significant trend in annual flows for the Kettle River at Laurier between 1981 and 2010.

A few months do exhibit declining average flows over the 30-year period between 1981 and 2010, but this claimed finding is of concern because if we choose the more recent 30-year period from 1984 to 2013, those few months with significant declining flows disappear and we end up with absolutely no months showing significant declining flow trends during the last three decades. The 1984 to 2013 annual flow series also doesn't have a significant trend over this time-frame. In fact, the correlation is positive towards increasing flows, not negative.

Details like this are critical. If you choose an analysis period with several low flow years at the end of it and/or high flow years at the start, a regression time series may be skewed to yield a non-robust declining trend that will disappear a few years later. Consequently, great caution must be exercised when making policy decisions based on short time series such as those only 30 years in length which contain unusually low (or high) values on either end.

This discussion paper referenced by the Globe and Mail also claims that "a new analysis of flow data for Laurier, Washington showed a small but meaningful downward trend in the volume of water flowing during three day and seven day low flows for the entire period of record (1929-2012) and from 1980-2012." Using the methods as described in the paper, I was unable to reproduce the results, even after cross-checking the results between the two approaches of (1) analyzing the USGS data for the Kettle River at Laurier with the Nature Conservancy's Indicators of Hydrologic Alteration program (i.e., the approach described in the discussion paper) and (2) obtaining the same data via the Environment Canada Water Survey of Canada database and manually generating the low-flow statistics with a separate spreadsheet.

Quite simply, I do not obtain the same input data for subsequent statistical analyses as is reported in the paper. My statistical tests also differ substantially in the magnitude of any significance/non-significance, but the overall conclusions are similar. Between 1929 and 2012, there is a significant decline in the 3-day minimum flows on the river, and between 1980 and 2012, there are significant declines in both the 3-day and 7-day minimum flows. But, once again, if we include the latest 2013 data, the significance of the post-1980 trends disappears -- showing the statistical conclusions are not robust if the addition of a single year's worth of new data changes the conclusions dramatically from significant to non-significant trends.

And over the past 30 years (i.e., since 1984) -- which is a more common climate science metric -- there has been absolutely no sign of a significant declining trend in either the 3- or 7-day minimum flows.

We cannot make rational policy choices if we are yo-yo-ing between statististical significance/non-significance by adding a year or two to an environmental data set. Overall, I'd like to see the Kettle River Watershed Management Plan re-examine their analyses and confirm (or correct) their already published results, and then update their initial analyses with the 2013 data to see if they reach the same conclusions regarding statistical non-significance as I did. Duplication is the key to good science, and is a must for framing solid water policies.

The more important concern is that the analyses appear to have been performed on the annual flow series, and in this region, the annual 3- and 7-day minimum flows often occur in the wintertime under ice cover. Flows measured during this time are also often unreliable due to ice cover, and can be systematically biased over time due to non-random changes in measuring devices and other factors. The core issue on the Kettle River from Hume's article seems to be the confluence of low flows in mid- to late-summer that lead to high water temperatures, which in turn harms aquatic life such as fish. Low flows in the middle of winter are irrelevant for these types of issues. Thus, we need to focus on the aquatic stressor at issue and isolate the appropriate flow trends accordingly -- ignoring flow trends that are unrelated to the topic at hand.

Consequently, when I reanalyze the Kettle River at Laurier low flow dataset for the 3- and 7-day minimum flows during the more ecologically relevant extended summer season (June through September), I find no significant trend either since records began, or during the last 30 years.

In the backgrounder for the 2011 BC Endangered Rivers list, Angelo goes on to claim that "in the past three summers, the Kettle River has experienced record low flows (so low at times that locals couldn't even tube down parts of the river)." This is another claim I cannot verify, since as best I can tell, none of the years between 2008 and 2011 contained record low flows during the summertime tubing season.

The lack of seemingly rigorous science and objective journalism surrounding water resources in British Columbia is something I've been concerned about for many years, and yet these types of problems continue to fester and expand with the full knowledge and approval of the public sector science establishment.View Comments

Sierra Rayne holds a Ph.D. in Chemistry and writes regularly on environment, energy, and national security topics. He can be found on Twitter at @srayne_ca