No Technical Reason for EPA Delay

There is no technical reason for EPA not to finalize the 2014 RFS volumes. According to EPA, “The four separate renewable fuel standards are based primarily on 49 state gasoline and diesel consumption volumes projected by EIA, and the total volume of renewable fuels by EISA] in the coming year.”[6]

Members of the Oversight Committee can question EPA on the decision-making process and on what or who specifically caused such a significant delay, given the lack of technical explanation. EPA will likely respond as it did in its notice of delay:

The proposal has generated significant comment and controversy, particularly about how volumes should be set in light of lower gasoline consumption than had been forecast at the time that the Energy Independence and Security Act was enacted, and whether and on what basis the statutory volumes should be waived. Most notably, commenters expressed concerns regarding the proposal’s ability to ensure continued progress towards achieving the volumes of renewable fuel targeted by the statute.[7]

However, the DC Circuit Court has

commented on the RFS in 2012, and its interpretation shows that EPA is not supposed to be only concerned about growth. Specifically, the Court stated:

EPA is correct that one of Congress’s stated purposes in establishing the current RFS program was to “increase the production of clean renewable fuels.”…But the general mandate does not mean that every constitutive element of the RFS program should be understood to individually advance a technology-forcing agenda, at least where the text does not support such a reading.[8]

This means that EPA’s written response is not sufficient because it is focused on ensuring continued increase in biofuel production despite admitted practical constraints. In its proposed rule for the 2014 requirements, EPA addressed this reality:

Relying on its Clean Air Act waiver authorities, EPA is proposing to adjust the applicable volumes of advanced biofuel and total renewable fuel to address projected availability of qualifying renewable fuels and limitations in the volume of ethanol that can be consumed in gasoline given practical constraints on the supply of higher ethanol blends to the vehicles that can use them and other limits on ethanol blend levels in gasoline.[9]

Since EPA has been told not to focus solely on the growth of biofuels and has acknowledged that more production does not make sense given the “blend wall”, this leaves few excuses for EPA to say it was not able to finalize the 2014 numbers. The only change since November 2013 and now is that biofuels lobbyists have strongly opposed an 8 percent reduction. However, this does not give EPA an excuse to forever drag its feet to avoid controversy.

Political Reasons

One of the only plausible reasons for EPA’s refusal to finalize the 2014 volumes requirements was political calculation. This is relevant because there has been much speculation that the Obama Administration purposely held up the process to help Bruce Braley and his Senate bid in Iowa. Politico explained:

Several sources following the issue closely say that the White House hoped that boosting the overall volumes would be enough to act as a boon to Braley. But renewable fuels advocates in the state aren’t happy with that compromise, so anything short of a clear victory for ethanol makers could hurt Braley’s campaign.

With Democratic control of the Senate hanging by a thread, the administration most likely doesn’t want to endanger the candidate’s election.

“If they increase the number, but it’s still tied to the blend wall, in our view, they will have killed the program, and that will be seen as a huge loss for Braley, and they’ll wait until after the election,” said one person in the biofuels industry.

“If it’s good for Braley, it’ll be before the election. If it’s bad for Braley, it’ll be a punt. And people will see the punt.”[10]

Another important question for EPA is how to ensure that there aren’t similar delays in the future and what the Agency will do to catch up on the backlog it produced.

Moving Targets with Cellulosic

In addition to missing its deadlines, EPA has created more ambiguity in the process by changing the definition of cellulosic biofuel to essentially allow for an energy product that is 75 percent cellulosic to count as if it is 100 percent cellulosic.[11] This had an immediate impact in the amount of “cellulosic” biofuels produced. For example, before EPA’s rule change, just 0.4 percent of the proposed 2014 requirement of 17 million gallons was produced. Now, there are over 18 million gallons of cellulosic. Amazingly, 97 percent of that fuel would not have qualified as cellulosic under EPA’s original definition.[12]

The problem is that this

new cellulosic ethanol is not actually cellulosic ethanol. It cannot be blended into fuel. According to EPA’s new accounting, currently more than 18 million Cellulosic RINs have been produced. RINs are Renewable Identification Numbers which are assigned to each gallon of cellulosic ethanol produced. These aren’t actual “gallons” of fuel, they are actually “credits” of fuel.

EPA reports that 7.8 million gallons of “renewable compressed natural gas” count as cellulosic biofuel, and 9.8 million gallons of “renewable liquefied natural gas” count as cellulosic biofuel. These are not gallons that refiners can blend into fuel. These are only credits that EPA will almost certainly try to force refiners to buy. This is essentially a tax on fuel with the proceeds going to renewable CNG and LNG producers.

This is significant because in 2012, a

federal court ruled that EPA could not require refiners to blend non-commercially available biofuels into gasoline. As noted above, EPA was supposed to predict the amount of cellulosic ethanol produced, not to promote cellulosic production. This remains a problem 2014. If EPA is calling biogas that is turned into “renewable liquefied natural gas” or “renewable compressed natural gas” cellulosic ethanol it is not predicting cellulosic production by redefining cellulosic production in order to incentivize it.

It appears that EPA is more interested in making it look like the RFS program is working (and rewarding renewable natural gas producers) instead of setting targets that are actually realistic. Even more concerning, this appears to be a political issue, since EPA singled out cellulosic as a priority for the Administration in its notice:

EPA has been evaluating these issues in light of the purposes of the statute and the Administration’s commitment to the goals of the statute to increase the use of renewable fuels; particularly cellulosic biofuels…[13]

Members of Congress could use this opportunity to press EPA on whether it has have been pushed by the Administration to make cellulosic work by changing the definition of what qualifies as a cellulosic fuel.

Conclusion

It is good that the Oversight Committee is highlighting EPA’s refusal to finalize the 2014 RFS volumes. EPA has caused a compliance nightmare by continuously missing their deadlines for no discernable technical reason, and EPA has tweaked the definition of cellulosic ethanol instead of lowering the numbers to a realistic level based on actual production. The RFS is fatally flawed, and EPA has shown that it is unable to properly carry out the law without injecting politics. It is up to Congress to fix the RFS, especially due to EPA’s inability to carry out the law.

[1]

Darren Goode, “McCabe to testify at House hearing on RFS delay”, POLITICO Pro Whiteboard, December 5, 2014 (subscription needed).

[2]

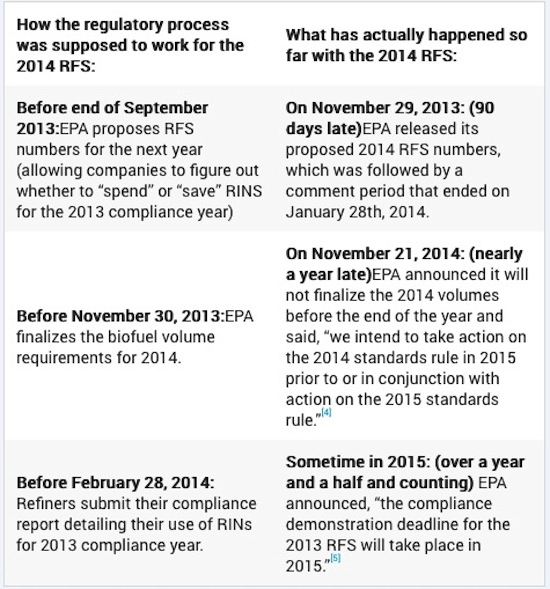

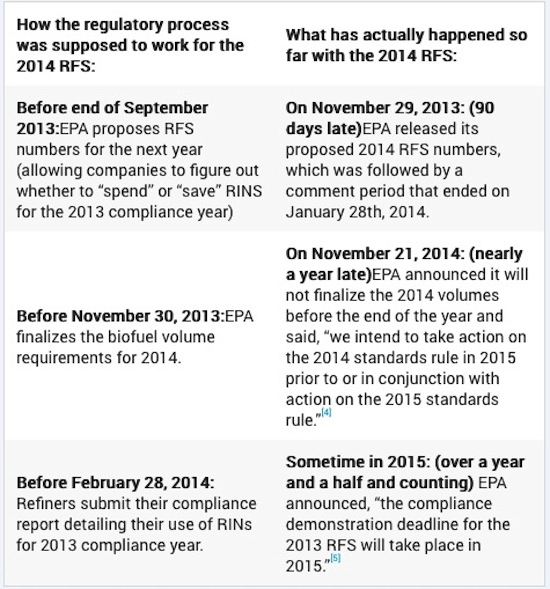

Environmental Protection Agency, “EPA Proposes 2014 Renewable Fuel Standards, 2015 Biomass-Based Diesel Volume”, Regulatory Announcement, November 29, 2013

[3]

Christopher Doering, “EPA’s ethanol mandate for 2014 behind schedule”, The Des Moines Register, June 27, 2014

[4]

40 CFR Part 80, “Notice of Delay in Issuing 2014 Standards for the Renewable Fuel Standard Program”, November 21, 2014

[5] Id.

[6]

40 CFR Section 14716(e)1

[7]

40 CFR Part 80, “Notice of Delay in Issuing 2014 Standards for the Renewable Fuel Standard Program”, November 21, 2014

[8] American Petroleum Institute v. Environmental Protection Agency, Case No. 12-1139, 9 (C.A. D.C., Jan. 25, 2013).

[9]

Environmental Protection Agency, 78 Fed. Reg. 238 (proposed November 29, 2013) (to be codified 40 CFR Part 80)

[10]

Erica Martinson, “White House may see no reason for pre-election biofuel move”, POLITICOPro, (subscription needed).

[11]

Institute for Energy Research, “EPA Moves Goalposts with New Definition for Cellulosic Biofuels”, October 15, 2014

[12]

Environmental Protection Agency, “RIN Generation Summary”, Data from November 10,2014

[13]

40 CFR Part 80 “Notice of Delay in Issuing 2014 Standards for the Renewable Fuel Standard Program”, November 21, 2014.