Any time there are claims that drinking water is in decline, the public will be alarmed. The question is whether they should be?

David Schindler from the

University of Alberta was interviewed for Hume's piece, and was quoted saying that "all of the lakes are turning into little puddles of green slime and, needless to say, people aren't happy about it." All of Canada's lakes are turning into little puddles of green slime? Statements such as these are so ridiculous on their face they warrant no further serious commentary. Another textbook example of over-the-top terrible science communication with the public that just serves to further dumb down the policy discussions.

Hume's article also claims that "river flows are declining and water is residing longer in lakes, concentrating pollutants." This got me looking at the actual flows in Canada's rivers over the past three decades.

From the

Environment Canada Water Survey of Canada database, I looked for trends in the annual average flows at the hydrometric stations having up to the top 20 largest gross drainage areas in each of Canada's ten provinces. The results can be found here. The criteria that needed to be generally met was to have a continuous annual flow series for 30 consecutive years ending in either 2010, 2011, 2012, or 2013 -- thereby capturing the most recent three decade long trend. For Manitoba and Quebec, the flow records were sufficiently incomplete as to prevent the use of but a small number of stations, and in Prince Edward Island and Nova Scotia, less than 20 stations were available that met the basic criteria for a rigorous examination of current flow trends.

Out of 146 total stations examined, only six (4 percent) had significant declining annual water yield trends, while 31 (21 percent) had significant increasing trends, and of the remaining 75 percent of the stations with non-significant trends, most had positive correlations towards more flow -- not less.

It is worth noting that I asked Hume where he obtained his river flow data source from. He didn't reply.

Back in 2010,

Statistics Canada published

an analysis of water yields across Canada for the time frame from 1971 to 2004. It is unclear why a study released in 2010 would end the data input in 2004, since hydrometric data is usually available soon after generation. As well, the choice of a period from 1971 to 2004 (i.e., 34 years inclusive) is odd. Furthermore, the early 1970s was a period of generally high stream flows across the country, skewing any resulting trend analyses.

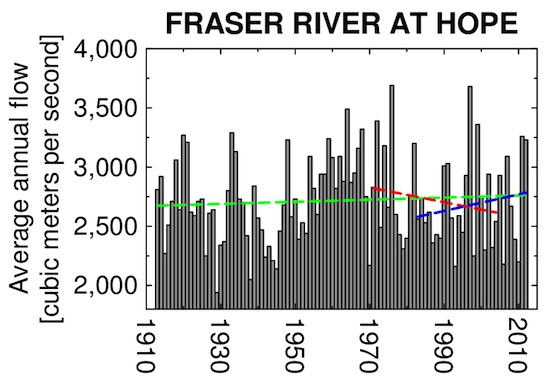

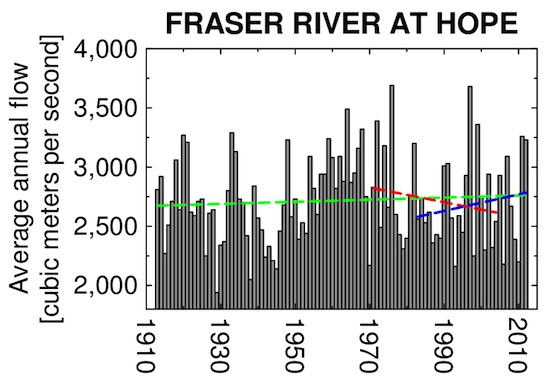

For example, here are the annual average flows for the furthest downstream active long-term hydrometric station on the Fraser River (08MF005: Fraser River at Hope) since records began in 1913.

The green line is a trend line using all the data from 1913 to 2012 (the latest year available). Note the slight positive slope towards increasing water yields (although the regression is non-significant). The red line shows a trend line using just the data from 1971 to 2004, which has a negative slope towards declining water yields (but, once again, the regression is non-significant). Finally, the blue line shows the trend from the last 30 years (i.e., 1983-2012), which has a positive slope towards increasing flows (but, yet again, is non-significant).

The take-home message is as follows. First,

Statistics Canada put out public reporting that appears to have failed to discuss whether or not their claimed water yield trends have statistical significance. By definition, if the trend is non-significant, there is no trend (a.k.a., you cannot reject the null hypothesis of no trend with any reasonable level of confidence). This is another example of terrible science communication to the public, and more basically, just bad science. Second, they chose a period that could be construed as "cherry-picking" in order to achieve the most likely occurrence of a declining trend.

Thus, if we look at either the complete flow record for the Fraser River at Hope, or the most recent three decade period, we would conclude water yields are not changing (since the trends are non-significant), but that since the correlations are positive, it is more likely that water yields in the Fraser River watershed are increasing over time, not decreasing. You can extrapolate this case study to the rest of the hydrometric stations across Canada, and it becomes evident how problematic it is to claim river flows are declining throughout the nation.

Overall, I see no evidence that there is a significant trend towards generally declining river flows in Canada as the

Globe and Mail article claims. And

Statistics Canada needs to start doing rigorous science if it wants to determine whether or not water yields across Canada are changing.

The green line is a trend line using all the data from 1913 to 2012 (the latest year available). Note the slight positive slope towards increasing water yields (although the regression is non-significant). The red line shows a trend line using just the data from 1971 to 2004, which has a negative slope towards declining water yields (but, once again, the regression is non-significant). Finally, the blue line shows the trend from the last 30 years (i.e., 1983-2012), which has a positive slope towards increasing flows (but, yet again, is non-significant).

The take-home message is as follows. First, Statistics Canada put out public reporting that appears to have failed to discuss whether or not their claimed water yield trends have statistical significance. By definition, if the trend is non-significant, there is no trend (a.k.a., you cannot reject the null hypothesis of no trend with any reasonable level of confidence). This is another example of terrible science communication to the public, and more basically, just bad science. Second, they chose a period that could be construed as "cherry-picking" in order to achieve the most likely occurrence of a declining trend.

Thus, if we look at either the complete flow record for the Fraser River at Hope, or the most recent three decade period, we would conclude water yields are not changing (since the trends are non-significant), but that since the correlations are positive, it is more likely that water yields in the Fraser River watershed are increasing over time, not decreasing. You can extrapolate this case study to the rest of the hydrometric stations across Canada, and it becomes evident how problematic it is to claim river flows are declining throughout the nation.

Overall, I see no evidence that there is a significant trend towards generally declining river flows in Canada as the Globe and Mail article claims. And Statistics Canada needs to start doing rigorous science if it wants to determine whether or not water yields across Canada are changing.

The green line is a trend line using all the data from 1913 to 2012 (the latest year available). Note the slight positive slope towards increasing water yields (although the regression is non-significant). The red line shows a trend line using just the data from 1971 to 2004, which has a negative slope towards declining water yields (but, once again, the regression is non-significant). Finally, the blue line shows the trend from the last 30 years (i.e., 1983-2012), which has a positive slope towards increasing flows (but, yet again, is non-significant).

The take-home message is as follows. First, Statistics Canada put out public reporting that appears to have failed to discuss whether or not their claimed water yield trends have statistical significance. By definition, if the trend is non-significant, there is no trend (a.k.a., you cannot reject the null hypothesis of no trend with any reasonable level of confidence). This is another example of terrible science communication to the public, and more basically, just bad science. Second, they chose a period that could be construed as "cherry-picking" in order to achieve the most likely occurrence of a declining trend.

Thus, if we look at either the complete flow record for the Fraser River at Hope, or the most recent three decade period, we would conclude water yields are not changing (since the trends are non-significant), but that since the correlations are positive, it is more likely that water yields in the Fraser River watershed are increasing over time, not decreasing. You can extrapolate this case study to the rest of the hydrometric stations across Canada, and it becomes evident how problematic it is to claim river flows are declining throughout the nation.

Overall, I see no evidence that there is a significant trend towards generally declining river flows in Canada as the Globe and Mail article claims. And Statistics Canada needs to start doing rigorous science if it wants to determine whether or not water yields across Canada are changing.