By Tina Trent -- BombThrowers —— Bio and Archives May 19, 2017

Comments | Print This | Subscribe | Email Us

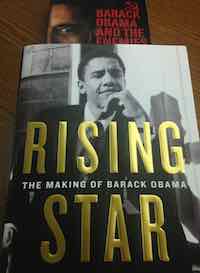

Even if you are not planning to read all 1,078 pages of text in David Garrow’s Obama biography, Rising Star: The Making of Barack Obama (the other 400 pages are mostly endnotes), I recommend you read the first chapter.

Titled “The End of the World as They Knew It,” Obama appears nowhere in it. Instead, the chapter details the death of the steel industry in Chicago’s South Side between 1980 and 1985, the deterioration of the community around the shuttered steel mills, and the rise of a community-organizer culture in the ashes of what used to be stable mill towns and stable minority communities.

Garrow chooses to begin his book with this vignette because South Chicago’s Rosewood community is where Obama began his career as a community organizer. It’s an interesting choice: Garrow is pointing at the politics and practices of grassroots organizing and saying: this is the authentic Obama — what he became later was inauthentic.

Saying this appears to be the main point of the book.

“Community organizer” is a title also preferred by Obama himself, who made sure his “organizer” credentials were front and center throughout all of his autobiographical work and political campaigns. Obama does not believe that he has betrayed his own identity as a left-wing political organizer, as Garrow thinks he did.

Even if you are not planning to read all 1,078 pages of text in David Garrow’s Obama biography, Rising Star: The Making of Barack Obama (the other 400 pages are mostly endnotes), I recommend you read the first chapter.

Titled “The End of the World as They Knew It,” Obama appears nowhere in it. Instead, the chapter details the death of the steel industry in Chicago’s South Side between 1980 and 1985, the deterioration of the community around the shuttered steel mills, and the rise of a community-organizer culture in the ashes of what used to be stable mill towns and stable minority communities.

Garrow chooses to begin his book with this vignette because South Chicago’s Rosewood community is where Obama began his career as a community organizer. It’s an interesting choice: Garrow is pointing at the politics and practices of grassroots organizing and saying: this is the authentic Obama — what he became later was inauthentic.

Saying this appears to be the main point of the book.

“Community organizer” is a title also preferred by Obama himself, who made sure his “organizer” credentials were front and center throughout all of his autobiographical work and political campaigns. Obama does not believe that he has betrayed his own identity as a left-wing political organizer, as Garrow thinks he did.Steelmaking was dangerous and strenuous work … but steelworkers had significant freedoms. “There were no time clocks, and they could come out for lunch,” a nearby barber recounted. “The workers figured they could get their hair cut on company time because it grows on company time.”This sort of time wasting, described as a right, will be familiar to anyone who deals with union workers. Later in the chapter, Garrow cites a troubling statistic: because of drinking on the job, by 1976, “46 percent of the steel shipped from Republic [Mill] was ‘rejected because it was not up to standards.’” According to Frank Lumpkin, similar problems existed at the mill where he worked. This sort of revelation is noteworthy. Noteworthy too is the inclusion of a critique of a major FHA – HUD program designed to boost minority home ownership. The program actually resulted in “massive numbers of foreclosed and abandoned properties,” market upheaval, bad debts, and community decimation, as unqualified applicants were approved for special loans. Garrow is not writing about the market collapse of 2008: this disastrous federal effort to address “redlining” in minority communities was implemented in 1968. Finally, Garrow does not shy away from the self-inflicted problems of the Rosewood community, namely crime. I don’t want to be misleading here: the vast majority of the interviews Garrow conducts are with activists from various leftist groups, and most of what is described is their activism. This sort of material is very useful in building a picture of the world Obama would come to apprentice in. But at every turn, it is a world where the sole answer for any problem is to claim victimization and demand reparations of some sort from somebody. Most of the chapter merely documents this in a long series of complaints and political actions. None of this is to say that the community’s problems are imaginary or mostly self-inflicted. But by walking too closely in the footsteps of people who believe in the inevitability of their politics, Garrow ends up avoiding other avenues of inquiry. Was another anti-redlining scheme or another march outside the shuttered factory’s gates really going to produce positive results? His narrative follows the activists’ trail where it leads. But he stays, virtually entirely, inside the world of that activism. Also not examined is the movement behind the local movement. Professionally trained activists drift in and out of the story, but it isn’t clear from where. The activism that is described is only the most local, though everywhere there are indications of a larger, even international movement choosing the issues to address, training the professional organizers who arrive and go, and providing salaries and ideological discipline. The main myth of community organizing is that any of it is really “community-based.” The activists come from elsewhere; the money comes from elsewhere (even if they say it doesn’t), and the locals and their problems are used quite openly as interchangeable props. Garrow could have delved more deeply into this. Perhaps he will do so in future chapters. I am, to be clear, making a judgment call based on reading only 4 percent of the book, though already it seems like 4 percent more than the New YorkTimes did. And Obama has not yet even arrived in Rosewood.

Tina Trent writes about crime and policing, political radicals, social service programs, and academia. She has published several reports for America’s Survival and helped the late Larry Grathwohl release a new edition of his 1976 memoir, “Bringing Down America: An FBI Informer with the Weathermen,” an account of his time infiltrating the Weather Underground.

Dr. Trent received a doctorate from the Institute for Women’s Studies of Emory University, where she wrote about the devastating impact of social justice movements on criminal law under the tutelage of conservative, pro-life scholar Elizabeth Fox-Genovese.

Dr. Trent spent more than a decade working in Atlanta’s worst neighborhoods, providing social services to refugees, troubled families, and crime victims. There, she witnessed the destruction of families by the poverty industry, an experience she describes as: “the reason I’m now a practicing Catholic and social conservative.”

Tina lives with her husband on a farm in North Georgia. She blogs about crime and politics at tinatrent.com.