Why the British and New Englanders needed to Conquer New France

Our tale of the many incidents that led to the Conquest of New France by the British, the British-colonial troops from New England and their Indian allies cannot be told solely by describing the terrible heartache, suffering and loss that was brought about by the many raids on peaceful British settlements by the French, the French colonial militia and their Indian allies. As mentioned, most of these raids were part of the plans of France to push the British out of North America, but were also an extension of their wars in Europe.

The raid on Schenectady occurred during King William’s War, 1689-97 and was the first of the wars in which England and France fought for the domination of North America. However, that raid was only part of a three pronged attack by the French and their Indian allies on the English colonial settlements. They also raided several villages along the Canadian border in New Hampshire, Maine and along the Maine coast. Many peaceful villagers were massacred. As the terror spread, a fierce anger grew among the English colonies and demands were made for the authorities to strike back at their tormenters.

First, the New England fought back by sending a fleet, commanded by Sir William Phips, to attack the French fort at Port Royal, Acadia (now Nova Scotia) in 1690. The fort was captured. The fleet then took an army of 2000 to capture Quebec City but were scattered by the French. For seven long years the border raids by the French and Indians continued with a few weak counter strikes, until the Treaty of Ryswick in 1697 when the war ended and Port Royal was returned to the French. An uneasy peace lasted for some six years but the war began again in 1703. Known as Queen Anne’s War, it was to last a very long “woeful” decade.

For the New England settlers and even the people of New France, life gradually returned to a semblance of calm and the normal life of daily sacrifice and toil. Some historians even felt that had it kept up, New France and New England might have been able to work out their differences. Such was not to be the case.

The Policy of the Governor Vaudreuil of New France:

To the Governor of New France, Philip de Rigaud, Marquis de Vaudreuil, this period of peace was not a satisfactory situation. He was an aggressive person, just itching to take action. He was imbued with the idea that it was a good policy to keep the Abernaki Indians who lived in the Adirondacks area to the north east, bordering on the English frontier continually irritated with their settlements. He openly stated his belief that it was “convenient” to maintain a secret alliance with the Indians and that a little pressure could induce forays into English territory and cause considerable damage, yet leave the French able to disclaim any responsibility.

It was easy to stir up the Indians who were enemies of the English settlers because of their expanding ownership of Abernaki lands. Though sold legally, their interpretation of the idea of “ownership” was not the same to the Indian as to the English mind. To the Abernaki, ownership meant the right to make use of the lands for farming, hunting and fishing, but not for exclusive private use and certainly not to be fenced off from Indian usage. To this tribe and others allied to the French, the English presented the greater threat because they were spreading over their lands in far greater numbers and at a faster rate than the French.

Vaudreuil’s aggressive plotting paid off in a reign of terror. In August 1703 the people of Wells were attacked, 39 were killed, mostly women and children or carried away to uncertain captivity. There were a small group of Frenchmen accompanying the raid but not named. The settlement near Saco Falls fell victim to the raiding; 11 were killed and 24 taken prisoner.

One by one other settlements were raided and paid their terrible toll. Spurwick and Scarborough; Cape Porpoise and Winter Harbour; each with a tale of horror. The final toll was estimated, by a second conservative count, at 160 killed; few of the men were carried off, most of those were women and children. That was by no means the end of it; the whole frontier for 200 miles was set aflame.

There are many tragic tales of the trek north and of the terrible experiences of the captives but one in particular stands out. She was a young mother who had just given birth, but the baby annoyed the Indians with its crying, so they dropped hot coals in its mouth and soon the child was no more. The young mother picked up her burden next morning and without complaint, continued the march north.

Governor Dudley of Massachusetts did all he could but it was impossible to protect all the isolated settlements and towns. He sent strong parties after the invaders, well armed and ready to retaliate in kind. They had strong incentives; the General Council of Massachusetts authorized a bounty of forty pounds per Indian scalp.

The Roman Catholic Aspect of Governor Vaudreuil’s policies:

To carry out the Governor’s policies Vaudreuil had a useful assistant, a Jesuit father by the name of Sebastien Râle (Rasle). He had come to Canada with Frontenac, spent some years in various mission fields, was proficient with languages and could speak the Algonquin dialect as well as that of the Hurons. In 1693 he was appointed missionary to the Abernaki.

Father Râle did not like the English settlements any more than his Abernaki associates. He saw them as an encroachment on Indian lands and a threat to his missionary efforts. Râle was a strong man of body and opinion but seriously short sighted. It was said to stem from an embittered patriotism and creed; although between the Puritan and Catholic creeds there was little to choose, both were rigid and unbending.

Father Râle was capable of tending to his Abernaki natives spiritual needs but he was also prepared should the governor wish, (as he had written to him) to incite the Abernaki to raise the hatchet against the English. This he did on numerous occasions and was in the thick of it. In the end he caused the destruction of the Abernaki and he himself eventually lay dead among his flock with a bullet through his forehead. Father Râle was not a lone practitioner of similar activities by Jesuit priests; it was not unusual.

Back to our Story;

When things seemed that they couldn’t get any worse for the citizens of New England, another blow from New France fell upon them; a surprising one too, because there appeared to be no apparent strategic reason that the town of Deerfield was targeted, being so distant from the northern frontier.

Deerfield, Massachusetts – February 29, 1704

Originally, the Deerfield location was a village of the Pocumtuk Indians but in 1664 the Mohawk Indians, their enemies, had destroyed it. The English chose the abandoned location to settle and gave it its present name. In 1675 the new village had been attacked by the Indians but survived. By 1704 the town had grown to about 283 people and was well established. It was located in a very isolated situation where there were no settlements to the west for 50 miles and no towns to the immediate north, so there was no easily obtained help if needed and they were therefore very vulnerable to attack. The enemy in Montreal was 300 miles to the North, the other side of a great wilderness.

During the spring and summer of 1703 there had been alarms. Lord Combury, Governor of New York had sent word that French soldiers and their Abernaki Indian allies from Maine were heading for Deerfield and the Connecticut Valley. Suddenly, in October a small Indian party captured two Deerfield men. The village strengthened their fortifications and a small contingent of 20 soldiers was sent to help defend the town. December was quiet and the cold seemed to promise respite from attack. The lesson of Schenectady, just 14 years before had been forgotten.

The town’s night watchman had ‘failed in his duty’ and in the dead stillness of winter while all the inhabitants of the palisaded town were asleep an attacking force of approximately 250 French and Indians, ordered by Governor-General Vaudreuil and under the command of Hertel de Rouville approached with deadly intent.

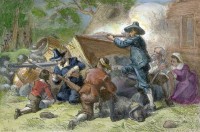

Silently, Rouville’s troops crossed the river and open fields in a deep snow that muffled all sound. Drifts of snow had piled up against the walls of the town making them easy to scale. A war hoop rang out and the attack began, just two hours before sunrise.

It is not necessary to describe the slaughter; it was a Schenectady situation once more. The victims bore the pain and suffering of unimaginable depravity yet once again.

At the end of the attack, although the townspeople and soldiers had put up a brave fight, the French and Indian force was too strong. Forty-one townspeople, men, women and children soon lay dead, wounded or dying and another 112 were taken prisoner. For them, the long 300 mile march north through the winter snows was about to begin.

Fortunately for history, some personal stories of the captives and survivors of the massacre have been recorded. Rather than focus on the raid itself, let their written records, sometimes in their own words, be told.

Stories of the survivors:

John Caitlin and his wife Mary (Baldwin) Catlin and their family:

No family suffered more than his. He was killed trying to defend his house. Their sons Joseph and Jonathan were also killed. Their married daughters Mary French and Elizabeth Corse were also killed on the long march to New France.

Mary’s (Baldwin) Catlin’s statement: “Being held with other prisoners in John Sheldon’s house, I gave a cup of water to a young French officer who was dying. He was perhaps the brother of Hertel de Rouvel.” It may have been gratitude for this act of kindness that she was left behind when the order came to march. She died of grief a few weeks later.

Elizabeth (Corse) Dumontet, Monettte; was the daughter of James and Elizabeth (Catlin) Corse and was just 8 years of age when she was captured and marched to New France. She was baptized a Catholic on 14 July 1705. At age 10 she asked to become a citizen.

In 1712, at La Prairie, she married Jean Dumontet a man 53 years of age He died after 17 years of marriage and Elizabeth after a year in 1730 married a man much younger than herself; Pierre Monet. Her eldest daughter married Pierre’s younger brother in 1732. After an eventful life she died at age 70 and was buried in La Prairie 30 January 1766.

John and Ruth Catlin’s story: John was born in 1687 and his sister Ruth in 1684. They both survived the rigors of the journey. Although delicate, Ruth was smart and capable of survival. The family story is that when she was tired of her burden, she would throw it back on the trail as far as possible. Her brother was worried she might be killed by the Indians but they just laughed and went back for it. They apparently acted towards her as if she were a great lady. When others went hungry, she had plenty of food to give John.

The same story says that John spent two years of captivity with a priest who was unable to convert him, but who supplied him with money and necessities when they parted. He was redeemed (ransomed) in 1706 and Ruth in 1707. He returned to Deerfield and raised a large family.

Thomas French’s Family:

He was the town blacksmith, town clerk and deacon. He and all his family were taken. His house was not burned down so all the town records were saved. His wife was Mary Catlin, daughter of John and Mary (Baldwin) Catlin. They were married 18 October 1683. She was killed on the trip to New France on 9 March 1704. He and their two eldest children were redeemed in 1706. He married again and died in 1733.

Two of their daughters stayed in New France, married and had large families. Their third daughter assimilated into the Indians in Kanawake. One great grandson was Archbishop Octave Plessis, who was the ranking churchman to champion the Catholic viewpoint to the British government in the first decades of the 1800s. That the Church survived is largely due to his efforts.

Joseph Kellog:

He was the son of Martin and Sarah (Dickinson / Lane). His mother wasn’t captured but his father and four children, including he, were carried away. Joseph was 12 at the time. He was more than a survivor. His statement tells his tale;

“I traveled to and fro among the French and Indians, learning the French language as well as those of the tribes of Indians I traded with, and Mohawks, and had got into a very good way of business, so as to get considerable monies and handsomely support myself and was under no restraint at all.”

He was perhaps the first New Englander to see the Mississippi River. In 1715 he returned. Always thereafter his skills were called on. He died in 1756 at Schenectady while on the expedition against Oswego. His brother Martin Kellog returned as did his younger sister Rebecca Joanna Kellog, age 11 in 1704; she married an Indian at Caughnawaga (Kahnawake) and there is a record of her visiting her brother in Connecticut.

The Stebbins Family:

John Stebbins, his wife, Dorothy and their six children were all captured. Not one was killed, probably because daughter Abigail had married Jean de Noyon, a French coureur de bois, living in Deerfield, on 3 February, 1704, just 26 days before the attack. John and his son John Jr. were redeemed, the rest of the children stayed in New France, became Catholic and were naturalized.

Apparently Jean had promised a better situation to his bride than he mastered, for in 1708 his wife petitioned for permission to take a mortgage to buy land in her own name to support her numerous family. Her siblings are poorly documented, but marriages for some of them are on record and the name Stebbings, in various spellings, is in the Montreal directory.

The Williams Family:

Perhaps the most intensive documentation of any family taken captive was that of the Williams family. Reverend John Williams, a Harvard graduate, was installed as minister in Deerfield in 1686. A year later he married Eunice Mather, a member of the widespread Puritan ecclesiastical family. He was a special target for captivity, as the Boston authorities held Jean Jean-Baptiste Guyon who New France wanted returned. His memoir of the events is the famed The Redeemed Captive Returning to Zion, first printed in 1707 and reprinted continually thereafter.

Their two little children and a Negro woman were killed in the assault. He, his wife, five children and a Negro man were taken. The eldest child alone was spared; he was away at school. His wife, having had a baby but a few weeks before, was very weak. On the second day of the journey north they said their farewells, and were separated. She fell down while wading a small river and “was plunged over her head and ears in the water. After which she traveled not far, for the cruel and blood thirsty savage slew her with his hatchet.”

His party took seven weeks to reach Fort Chambly. During his captivity he was constantly pressured to convert to Catholicism, but ignored all blandishments. He encouraged his fellow captives as much as possible. He was redeemed along, with 60 other captives, and arrived in Boston on 21 November 1706 with great joy.

Four of their children were redeemed and returned to New England, one continuing in the ministry. The one that remained was the subject of endless communications between New England, Albany, and Montreal. She was Eunice Williams, who lived in Cawhnawaga (Kahnawake). She received a Mohawk name A’ongote which means “she (was) taken and placed (as a member of their tribe).” In early 1713 she married an Indian named Arosen. They had at least three children, two daughters and a son. Both daughters married Indian men, one of whom became the grand chief of the village, the other also a prominent figure. The fact that the daughters married so well indicated that Eunice was held in high esteem in her adoptive tribe.

A study of the known facts about Eunice has recently been published under the apposite title, The Unredeemed Captive.

Mehuman Hinsdale

He was the first white child born in Pocumtuk / Deerfield in1673. His father, grandfather, and two Hinsdale uncles were killed at Bloody Brook. His only child was killed in the 1704 attack. He and his wife were marched to New France with the rest of the captives. In 1706 they were redeemed but then in April, 1709, he was again “captivated” and forced to run the gauntlet. After the war he was sent to France, then exchanged to London, and returned to Rhode Island, whence he got home in safety.

Summary of the raid on Deerfield

In approximate numbers, of the 283 residents of Deerfield, 41 were killed plus 7 others not from the town. Of the 112 on the forced march to New France 21 died, of these 7 were children ages 2 to 12.

Your Host’s Comments (Ken Tellis and Dick Field)

The tragedy of Deerfield, and all the trial and suffering it and other attacks represented in families destroyed or torn apart and separated for years or forever is hard to comprehend. In terms of survival of the town members of Deerfield, from the beginning of the raid to the redeeming of the last hostage, 130 in total, the raid is remarkable. As a consequence, Deerfield did survive and lives peacefully today with its rich history of early settlement. The city has never forgotten its past. It is remembered.

You will perhaps notice we have used the term New France instead of the source usage of the term Canada. There was no Canada in 1704 and Canada did not exist until after the conquest of Quebec and Montreal in 1759-60 and until the Treaty of Paris in 1763 was signed. With that treaty, all French possessions east of the Mississippi, including New France were given up in exchange for the rich sugar island of Guadeloupe. France also retained possession of the two tiny islands of Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Gulf of the St. Lawrence River.

Similarly, the “English” as referred to in the document were New England colonists primarily of British descent but composed of many people born in North America as well as directly from the British Isles and Holland but primarily from England, at that time. To the French and all in New France they were “les Anglais” (the English).

In 1707 Scotland joined England and then all became officially British with a new Union flag composed of the Cross of St. George of England and the Cross of St. Andrew of Scotland, although a very similar flag had been authorized to be flown on all British ships since 1607, 100 years earlier.

In Chapter 1, we asked the Question, “Why was Quebec City Attacked.” We began the answer by describing the massacre at Schenectady as being a one of the first causes of inciting the anger of the New Englanders over the brutal activities of the French and their Indian allies.

In this Chapter 2, we expanded on the terrible conditions imposed upon the New England towns, villages, isolated settlements and individual farms all along their frontiers and deep into their territory. The responses of the British and colonial forces to these attacks were unfortunately few, weak and none too successful. Obviously, the situation could not be tolerated forever, something had to be done. That is what this entire story is all about. But to figure out the reasons for Deerfield attack, we have to go back a quite a few years and describe a number of seemingly unrelated but dramatic events.

Chapter 3 will follow an exclusively French and Indian series of events that may answer why they would have chosen isolated Deerfield as a focus of their attack, quite aside from Governor Vaudreuil’s aggressive policies. These adventures are incredible and throw light on scenes most of us know little about. You will not want to miss Chapter 3.

Look for that great story about two weeks from today and don’t forget to write a note to Ken or Dick to have your friends or family, school or associations placed on our mailing list or to comment upon our adventures in time travel to date.

Bibliography

We will mention only the major sources because we would like anyone who wishes specific information to ask. There are a variety of sources and since most of our readers are on line, it is interesting to do some simple searches via Google or your favourite search engine.

The Preface; a reader asked where we got the population numbers of New France vs. New England, in 1759-60. Answer; there is a range of numbers described by various authors. We took a median number. Example; Population Numbers for all French in New France and North America range from 55,000 to 70,000 people We took 65,000.

For the St. Lawrence River and Gulf only, the numbers range from 45,000 to 55,000. We took 50,000. For New England, the range ran from 1,100,000 people to 1,500,000, we chose 1,300,000.

One URL is:

Chapter 1; please Google “Schenectady Massacre,” there’s lots there.

Chapter 2, Stories of survivors: These records were obtained from the New England Society: War and Society in Colonial Deerfield, Richard I. Melvoin (1989). Google “Deerfield Massacre” You will find it and many other references.

Source re Governor-General Vaudreuil’s policies and his assistant, Father Sebastiene Râle’s activities and the story of the massive strikes against the New England colonies: Volume 2 of the Canadian History series, “Century of Conflict,” Chapter XIV by John Lister Rutledge published 1956 by Double Day and Co., New York.

Interactive History

If your ancestors were part of our story, then you and your family are part of this adventure. Tell us about it and we will be delighted to make mention of it in our story. We will not publish anything before we obtain your approval. There are hundreds of thousands of you out there; Native people, Quebecois, Canadien, Canadians, Americans, and so many others beyond measure. We have heard from one person already, we will tell his story in Chapter 3.

Many thanks for your questions and comments and we look forward to hearing from you. You may contact Ken or Dick by writing to:

Letters@canadafreepress.com

Ken Tellis is an ex sailor who has traveled the world lived in Quebec and raised a family in the French milieu. Ken can be reached at  - Dick Field and Ken Tellis

(A note to new adventurers: if you have just joined our tale of the true history of the Conquest of New France and the many sacrifices all our forbearers made, leading to the formation of the United States, Canada and even today’s Quebec. Please make sure you read the Preface and Chapter 1 first. It will give you the background you need to understand the story to this point. To get yourself, your children, your family, your friends or school, library or others on our mailing list for future episodes Ken Tellis or Dick Field can be reached at letters@canadafreepress.com)

- Dick Field and Ken Tellis

(A note to new adventurers: if you have just joined our tale of the true history of the Conquest of New France and the many sacrifices all our forbearers made, leading to the formation of the United States, Canada and even today’s Quebec. Please make sure you read the Preface and Chapter 1 first. It will give you the background you need to understand the story to this point. To get yourself, your children, your family, your friends or school, library or others on our mailing list for future episodes Ken Tellis or Dick Field can be reached at letters@canadafreepress.com)