By Dan Calabrese ——Bio and Archives--June 14, 2018

American Politics, News | CFP Comments | Reader Friendly | Subscribe | Email Us

Interest rates can be too high, but they can also be too low. And they’ve been too low for a decade, in large part because the Fed was overcompensating for the mortgage market meltdown of 2008 in order to make credit easier. Remember when everyone was so freaked out that the credit markets were going to completely freeze up and that no one could get financing for anything?

Both the Bush and Obama Administrations were obsessed with the imperative to get America lending again! (Because bad debt contributed nothing to the problem in the first place, you understand.)

Interest rates can be too high, but they can also be too low. And they’ve been too low for a decade, in large part because the Fed was overcompensating for the mortgage market meltdown of 2008 in order to make credit easier. Remember when everyone was so freaked out that the credit markets were going to completely freeze up and that no one could get financing for anything?

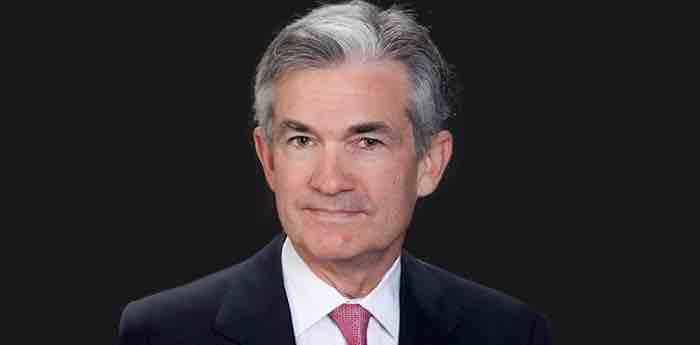

Both the Bush and Obama Administrations were obsessed with the imperative to get America lending again! (Because bad debt contributed nothing to the problem in the first place, you understand.)The latest increase, the second this year, will bring the benchmark federal-funds rate to a range between 1.75% and 2%. Officials penciled in a total of four rate increases for this year, up from a projection of three increases at their March meeting. “The economy is doing very well,” Fed Chairman Jerome Powell said at a news conference after the meeting. “Most people who want to find jobs are finding them, and unemployment and inflation are low.”

In its postmeeting statement, the Fed’s rate-setting committee said it “expects that further gradual increases in the target range for the federal-funds rate will be consistent with sustained expansion of economic activity, strong labor market conditions, and inflation near the committee’s symmetric 2% objective over the medium term.” Eight of 15 officials now expect at least four rate increases will be needed this year, up from seven in March and four in December. Most officials expect the Fed would need to raise rates at least three more times next year and at least once more in 2020, leaving rates in a range between 3.25% and 3.5% by the end of 2020, the same end point officials projected in March. The new interest-rate guidance shows the U.S. central bank is effectively sticking to a plan to continue raising short-term rates after they reach the level Fed officials expect would neither stimulate nor slow the economy, a so-called neutral level. It also suggests officials expect to reach that neutral level slightly sooner than before.What this means for the economy writ large is that there’s enough growth and productivity now that people who need credit can afford to obtain it on normal terms that reflect real market conditions, and the Fed no longer feels it’s necessary to goose the credit markets to keep people from being frozen out. It also means that lenders don’t have to suck up more risk than they should because they have to work with shackled interest rates. By the way, if you’re actually good at saving and limit your borrowing, higher interest rates are great news for you. Now, here’s something to keep an eye on: In a given year’s federal budget, interest in the debt usually runs under $200 billion, which is certainly not chicken feed, but it’s not a real reflection of what it costs the market to keep lending Uncle Sam money. When interest rates get real again, interest on the debt could soar to $400 or $500 billion a year, which will cause the deficit to soar and might finally get a few people questioning why we never get federal spending at least enough under control that it matches tax receipts. At least it should get people asking that question. To date, nothing else has.

View Comments

Dan Calabrese’s column is distributed by HermanCain.com, which can be found at HermanCain

Follow all of Dan’s work, including his series of Christian spiritual warfare novels, by liking his page on Facebook.