By John Treadwell Dunbar ——Bio and Archives--July 22, 2012

Travel | CFP Comments | Reader Friendly | Subscribe | Email Us

Located near the confluence of the Laramie and North Platte rivers near the Nebraska border in wide, open country populated by sprawling ranches and small Western towns, and low hills and shallow ravines where pine trees grow, the refurbished 19th-century military post of Fort Laramie stands as a vivid reminder of America's westward migration, a fifty-year saga of epic proportions brimming with tales of triumph and tragedy, hope and despair, honor, treachery and greed, which continue to resonate in vivid detail through the annals of American history.

During these tumultuous years from 1834 to 1890, Fort Laramie played a central role, in one guise or another, in the opening and settlement of the West. The European-American legacy began in the 1830s when it was known first as Fort William, then Fort John, and served as a hub in the lucrative fur trade business.

Located near the confluence of the Laramie and North Platte rivers near the Nebraska border in wide, open country populated by sprawling ranches and small Western towns, and low hills and shallow ravines where pine trees grow, the refurbished 19th-century military post of Fort Laramie stands as a vivid reminder of America's westward migration, a fifty-year saga of epic proportions brimming with tales of triumph and tragedy, hope and despair, honor, treachery and greed, which continue to resonate in vivid detail through the annals of American history.

During these tumultuous years from 1834 to 1890, Fort Laramie played a central role, in one guise or another, in the opening and settlement of the West. The European-American legacy began in the 1830s when it was known first as Fort William, then Fort John, and served as a hub in the lucrative fur trade business. The grass was green and the sky deep blue when we visited last June. It was getting hot and few visitors were about. That morning we toured the impressive Oregon Trail Ruts and iconic Register Cliffs at Guernsey a few miles back down Highway 26. As the day wore on I was becoming increasingly impressed with our discovery, especially on the approach to Fort Laramie which lies near a small town bearing the same name.

The grass was green and the sky deep blue when we visited last June. It was getting hot and few visitors were about. That morning we toured the impressive Oregon Trail Ruts and iconic Register Cliffs at Guernsey a few miles back down Highway 26. As the day wore on I was becoming increasingly impressed with our discovery, especially on the approach to Fort Laramie which lies near a small town bearing the same name.

The sheer size of the grounds caught me by surprise – galloping horses and military parades need a lot of room, I suppose. I was also taken back by the number of buildings, large and small, aligned in military precision; restored structures include the lime-concrete commissary store house (visitors center), the old bakery (1876), new guard house (1876), the captain's quarters (1870), the stone magazine (1858), the cavalry barracks (1874), and the two-story “Old Bedlam” (1849) built to house bachelor officers and the oldest documented building in Wyoming, two-stories tall and painted pure white now. Some glowed in exquisite refurbished condition, while others suffered in various stages of collapse, or stood as mute ruins. All that remains of the long, rectangular outline of the infantry barracks of 1867 are worn-down footers. To add to the ambiance, a large contingent of soldiers in blue with carbines at shoulder-arms marched back and forth across the parade grounds in the imagination of my mind. They stepped smartly in cadence, glancing occasionally over their shoulders at the sky.

The sheer size of the grounds caught me by surprise – galloping horses and military parades need a lot of room, I suppose. I was also taken back by the number of buildings, large and small, aligned in military precision; restored structures include the lime-concrete commissary store house (visitors center), the old bakery (1876), new guard house (1876), the captain's quarters (1870), the stone magazine (1858), the cavalry barracks (1874), and the two-story “Old Bedlam” (1849) built to house bachelor officers and the oldest documented building in Wyoming, two-stories tall and painted pure white now. Some glowed in exquisite refurbished condition, while others suffered in various stages of collapse, or stood as mute ruins. All that remains of the long, rectangular outline of the infantry barracks of 1867 are worn-down footers. To add to the ambiance, a large contingent of soldiers in blue with carbines at shoulder-arms marched back and forth across the parade grounds in the imagination of my mind. They stepped smartly in cadence, glancing occasionally over their shoulders at the sky.

I had forgotten we were now on the far western fringe of Tornado Alley, and paused mid-step at the not-too-subtle warning displayed at the visitors center heeding all to take shelter here in the concrete bunker in the event of the unimaginable. But not today, I thought, searching the sky for menacing clouds, envisioning all of these beautiful buildings exploding into splinters, and teams of bellowing oxen bound for ox heaven lifting off in flight, and covered wagons spilling silverware and bedding and hand tools and the kids and the family Bible like confetti across the prairie as they're sucked skyward into the spinning, black, serpentine funnel of a CAT-5, while the brave marching men of the 7th Infantry cried as they soiled their dress blues and ran for the store house.

I had forgotten we were now on the far western fringe of Tornado Alley, and paused mid-step at the not-too-subtle warning displayed at the visitors center heeding all to take shelter here in the concrete bunker in the event of the unimaginable. But not today, I thought, searching the sky for menacing clouds, envisioning all of these beautiful buildings exploding into splinters, and teams of bellowing oxen bound for ox heaven lifting off in flight, and covered wagons spilling silverware and bedding and hand tools and the kids and the family Bible like confetti across the prairie as they're sucked skyward into the spinning, black, serpentine funnel of a CAT-5, while the brave marching men of the 7th Infantry cried as they soiled their dress blues and ran for the store house.

Tradition has it that around 1820 Jacques La Ramee set out from the area of present day Fort Laramie to do some trapping on his own and was never heard from or seen again. Most likely he was killed by Arapahoe Indians who stuffed the trespassing Frenchman's corpse into a beaver dam, but who really knows? And that's how we ended up with the Laramie (La Ramee) River, Laramie Mountains, a city and tiny town of the same name, and Fort Laramie itself.

Tradition has it that around 1820 Jacques La Ramee set out from the area of present day Fort Laramie to do some trapping on his own and was never heard from or seen again. Most likely he was killed by Arapahoe Indians who stuffed the trespassing Frenchman's corpse into a beaver dam, but who really knows? And that's how we ended up with the Laramie (La Ramee) River, Laramie Mountains, a city and tiny town of the same name, and Fort Laramie itself.

Trade in fur was big business during the 1830s and '40s, and the confluence of the Laramie and North Platte served as an ideal location for bartering with the Sioux and Cheyenne. The most valued commodity sought by the white man were buffalo robes harvested from a never-ending-supply of bison that roamed the plains in the millions. Little did they know. In exchange the Indians received pretty beads and dirty blankets infested with the white man's diseases like smallpox and measles which proved fatal to the indigenous populations who lacked immunity and were subsequently decimated in large numbers across the West. The Indians also traded their furs for the essentials: liquor, sugar, tobacco, gun powder and lead shot, which today could rightfully be called “giving aid and comfort to the enemy.”

Trade in fur was big business during the 1830s and '40s, and the confluence of the Laramie and North Platte served as an ideal location for bartering with the Sioux and Cheyenne. The most valued commodity sought by the white man were buffalo robes harvested from a never-ending-supply of bison that roamed the plains in the millions. Little did they know. In exchange the Indians received pretty beads and dirty blankets infested with the white man's diseases like smallpox and measles which proved fatal to the indigenous populations who lacked immunity and were subsequently decimated in large numbers across the West. The Indians also traded their furs for the essentials: liquor, sugar, tobacco, gun powder and lead shot, which today could rightfully be called “giving aid and comfort to the enemy.”

Compared to the Indian wars that erupted in the 1860s and '70s, relations between whites and Indians during the early fur-trading years were relatively cordial, commerce being the mitigating factor that took precedence over collecting scalps. And the advancing Eastern sea of humanity had yet to stake its claim on Indian property. But those semi-civilized days changed dramatically by 1843 when the great emigrant migrations began in earnest and attacks on wagon trains increased, though all told few such attacks actually unfolded over the course of the migration. That's when concerted political deal-making between the federal government and Native Americans began to take shape.

Compared to the Indian wars that erupted in the 1860s and '70s, relations between whites and Indians during the early fur-trading years were relatively cordial, commerce being the mitigating factor that took precedence over collecting scalps. And the advancing Eastern sea of humanity had yet to stake its claim on Indian property. But those semi-civilized days changed dramatically by 1843 when the great emigrant migrations began in earnest and attacks on wagon trains increased, though all told few such attacks actually unfolded over the course of the migration. That's when concerted political deal-making between the federal government and Native Americans began to take shape.

Fort Laramie played a central role in hosting major treaty councils over the years aimed at keeping the peace, great gatherings of the whose-who in the Indian world, like the Horse Creek Treaty of 1851 which drew 10,000 Indians to Fort Laramie. The government agreed by treaty, among other things, to pay off the Indians with annuity goods if they would refrain from attacking the wagon trains. As expected the deal fell through, the treaty unraveled and by the 1860s attacks on the Oregon Trail and throughout the region increased.

Fort Laramie played a central role in hosting major treaty councils over the years aimed at keeping the peace, great gatherings of the whose-who in the Indian world, like the Horse Creek Treaty of 1851 which drew 10,000 Indians to Fort Laramie. The government agreed by treaty, among other things, to pay off the Indians with annuity goods if they would refrain from attacking the wagon trains. As expected the deal fell through, the treaty unraveled and by the 1860s attacks on the Oregon Trail and throughout the region increased.

This was eventually followed by another attempt via treaty to buy peace, but these efforts were also doomed at inception when famed leader Red Cloud learned the army was building three forts deep in Indian lands up north along the Bloody Bozeman Trail where thousands of miners were headed to the gold and silver fields of Montana. What followed was the Red Cloud War of 1866-1868 which ended, if I have my history right, when the U.S. removed the forts and cleared out.

This was eventually followed by another attempt via treaty to buy peace, but these efforts were also doomed at inception when famed leader Red Cloud learned the army was building three forts deep in Indian lands up north along the Bloody Bozeman Trail where thousands of miners were headed to the gold and silver fields of Montana. What followed was the Red Cloud War of 1866-1868 which ended, if I have my history right, when the U.S. removed the forts and cleared out.

The Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868, which among other things, allowed certain Native Americans to hunt beyond the reservation, was also torn to shreds by 1874 when gold was discovered in the Dakota Black Hills and hordes of gold diggers swarmed with pick and shovel in hand over the reservation and made a mess of the place. Gold fever, and the government’s inability or unwillingness to prevent the illegal incursion, resulted in the great Sioux Campaign of 1876 uniting such notables in battle as Crazy Horse, Sitting Bull, and other lesser known tribes.

And there I stood in the shade of “Old Bedlam” surrounded by such a great cloud of history watching smoke rise from thousands of Lakota teepees pitched at random whose inhabitants were gathered at Fort Laramie for diplomatic discourse, and a show of force, committing their respective understandings of their agreements to treaty, in English, words in funny script which weren't worth the paper they were scribbled on.

As a general rule, I've read, soldiers garrisoned at Fort Laramie rarely engaged in serious combat with the exception of the Battle of the Rosebud in 1876. Neither was Fort Laramie under threat of attack, but served as the primary staging area for the war effort, and functioned as a major communications center interconnecting the vast region, and a supply center.

The best part of our visit was wandering in and out of a dozen or so buildings fixed up like it was 1872. Not only have building exteriors and interiors been resurrected, but rooms are furnished with dress, décor and implements of 19th-century military life; bunks and tack, uniforms hanging, mess tables aligned and waiting for grub to be served. An extraordinary amount of detail and effort has been expended to authenticate the fort. Displayed behind glass are the living and dining quarters of the upper-echelon officers' corps and their wives, who lived lives of relative luxury from the looks of it; fine table cloths, fine china and other accoutrements of the Victorian Era; handsome rugs and soft beds and comfortable chairs. Boots and bridles, carbines and razors, pots and pans and horseshoes and spurs, and you name it, it's all inside these wonderfully restored buildings, clean, orderly and everything in its proper place as though it really were 1872, without the horse manure and flies to contend with, or tuberculosis, or all the tobacco smoke, and the guns going off all day long, and the senseless marching back and forth, and the KP and cleaning out the latrines and the sheer boredom of waiting for your five-year enlistment to be over and done with - no wonder they had a thirty-percent desertion rate.

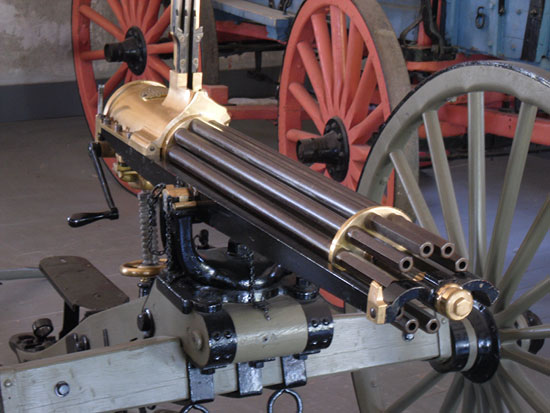

And if that's not enough to take you back in time, keep an eye out for park personnel walking the grounds dressed in period pieces. And whatever you do, make sure you stop by the New Guard House (1876) which houses a large collection of death-dealing field pieces. My favorite by far was the Gatling gun which up to then I had only seen on the silver screen.

By the end of two hours I had had enough history to last me a week. Hearing a shout in my head and the clippity-clop of hooves I looked up and watched one of those Pony Express riders trot into the fort on a tired palomino, slowly get off and switch to an anxious bay, and slowly trot on to California. Well, that's one myth shattered. I could have sworn they raced at breakneck speed every step of the way.

When it was time to head back to the parking lot I switched into my James Bond mode, sprinting from building to building and plastering my sweaty back against the wall, heart pounding, palms all sweaty, and looking up, always looking up. Not one to take unnecessary risks I knew it was just a matter of time before those big, fat oxen fell back to

earth and rained down on Fort Laramie like cats and like dogs, landing rather abruptly with a mighty, and a very messy, THUMP!

The Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868, which among other things, allowed certain Native Americans to hunt beyond the reservation, was also torn to shreds by 1874 when gold was discovered in the Dakota Black Hills and hordes of gold diggers swarmed with pick and shovel in hand over the reservation and made a mess of the place. Gold fever, and the government’s inability or unwillingness to prevent the illegal incursion, resulted in the great Sioux Campaign of 1876 uniting such notables in battle as Crazy Horse, Sitting Bull, and other lesser known tribes.

And there I stood in the shade of “Old Bedlam” surrounded by such a great cloud of history watching smoke rise from thousands of Lakota teepees pitched at random whose inhabitants were gathered at Fort Laramie for diplomatic discourse, and a show of force, committing their respective understandings of their agreements to treaty, in English, words in funny script which weren't worth the paper they were scribbled on.

As a general rule, I've read, soldiers garrisoned at Fort Laramie rarely engaged in serious combat with the exception of the Battle of the Rosebud in 1876. Neither was Fort Laramie under threat of attack, but served as the primary staging area for the war effort, and functioned as a major communications center interconnecting the vast region, and a supply center.

The best part of our visit was wandering in and out of a dozen or so buildings fixed up like it was 1872. Not only have building exteriors and interiors been resurrected, but rooms are furnished with dress, décor and implements of 19th-century military life; bunks and tack, uniforms hanging, mess tables aligned and waiting for grub to be served. An extraordinary amount of detail and effort has been expended to authenticate the fort. Displayed behind glass are the living and dining quarters of the upper-echelon officers' corps and their wives, who lived lives of relative luxury from the looks of it; fine table cloths, fine china and other accoutrements of the Victorian Era; handsome rugs and soft beds and comfortable chairs. Boots and bridles, carbines and razors, pots and pans and horseshoes and spurs, and you name it, it's all inside these wonderfully restored buildings, clean, orderly and everything in its proper place as though it really were 1872, without the horse manure and flies to contend with, or tuberculosis, or all the tobacco smoke, and the guns going off all day long, and the senseless marching back and forth, and the KP and cleaning out the latrines and the sheer boredom of waiting for your five-year enlistment to be over and done with - no wonder they had a thirty-percent desertion rate.

And if that's not enough to take you back in time, keep an eye out for park personnel walking the grounds dressed in period pieces. And whatever you do, make sure you stop by the New Guard House (1876) which houses a large collection of death-dealing field pieces. My favorite by far was the Gatling gun which up to then I had only seen on the silver screen.

By the end of two hours I had had enough history to last me a week. Hearing a shout in my head and the clippity-clop of hooves I looked up and watched one of those Pony Express riders trot into the fort on a tired palomino, slowly get off and switch to an anxious bay, and slowly trot on to California. Well, that's one myth shattered. I could have sworn they raced at breakneck speed every step of the way.

When it was time to head back to the parking lot I switched into my James Bond mode, sprinting from building to building and plastering my sweaty back against the wall, heart pounding, palms all sweaty, and looking up, always looking up. Not one to take unnecessary risks I knew it was just a matter of time before those big, fat oxen fell back to

earth and rained down on Fort Laramie like cats and like dogs, landing rather abruptly with a mighty, and a very messy, THUMP!View Comments

John Treadwell Dunbar is a freelance writer