Gun control advocates have long promoted a wide range of policies and laws intended to restrict the "right of the people to keep and bear arms."

Their arguments follow the direction that while broad, sweeping laws to eliminate private gun ownership and use would be ideal, even small, incremental restrictions on ownership and use (e.g., background checks prior to purchase, gun registries, etc.) would be a clear step in the right direction and would provide measurable reductions in the rate of gun crime. Canada has run the latter experiment, and the results in no way support gun control efforts.

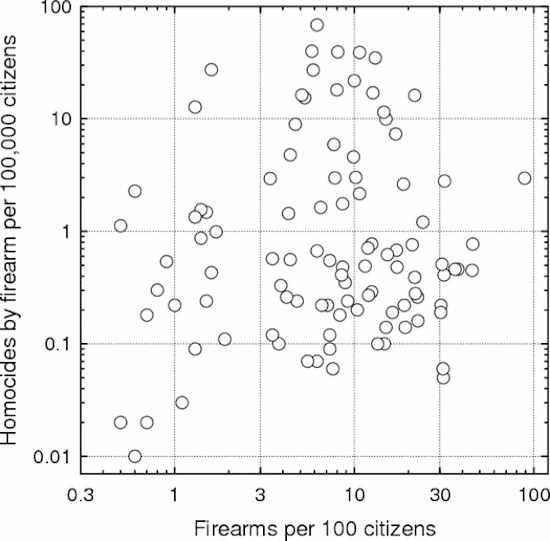

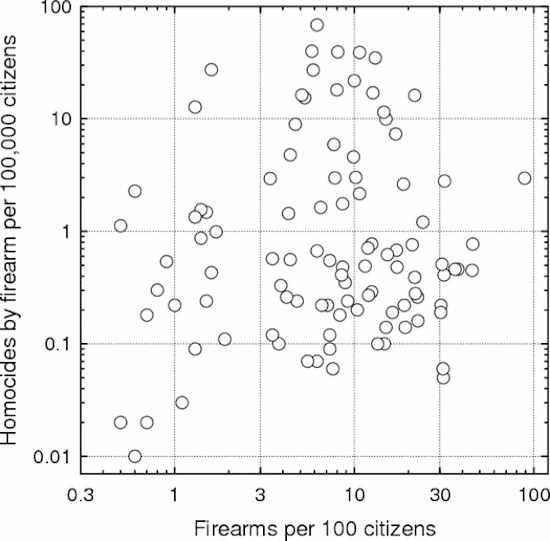

Before looking at the Canadian data in detail, it is useful to consider the global relationship between the firearm ownership rate and the corresponding homicide rate by firearms, as shown in the chart below using

data for 102 nations (including the USA, of course).

There is no significant correlation between the rate of gun ownership and the homicide rate by guns among these countries.

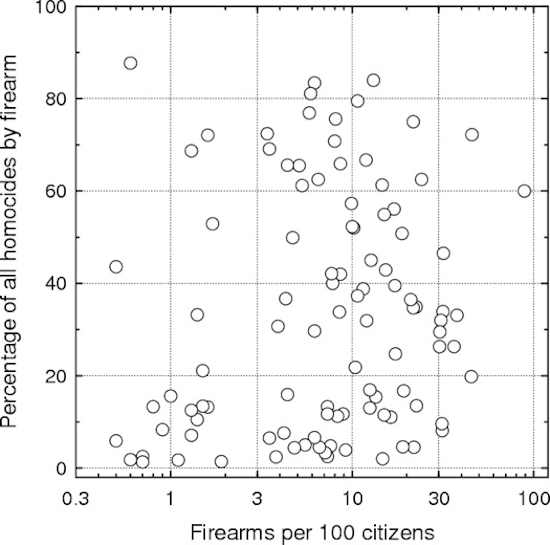

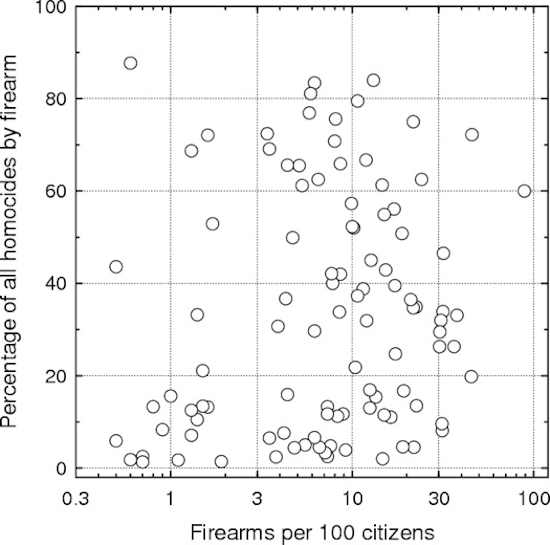

Similarly, we see no significant correlation between the rate of gun ownership and the percentage of homicides by firearm within this group of nations.

Moving back to the Canadian gun control experiment, and as noted in the Royal Canadian Mounted Police 2010

report on this topic, "[i]n 1993, the Federal Government indicated its intention to proceed with additional [gun control] measures, including a universal licensing system that would apply to individuals and a universal registration system that would apply to all firearms. Senate approval and Royal Assent for

Bill C-68 (

An Act Respecting Firearms and Other Weapons to create the

Firearms Act) were granted on December 5, 1995."

Key provisions of the Canadian law included the following:

- the requirement for licenses in order to possess and acquire firearms and buy ammunition

- the registration of all firearms, including rifles and shotguns

- Criminal Code amendments providing stricter penalties for certain serious crimes where firearms are used (e.g., kidnapping, murder, etc.) and classifying all .25 and .32 caliber handguns, as well as those with a barrel length of 105 mm or less, as prohibited firearms

On October 25, 2011, the governing Conservative Party of Canada introduced

Bill C-19, formally called "An Act to amend the Criminal Code and the Firearms Act" with the more precise short title of "Ending the Long-gun Registry Act." The legislation was subsequently passed in the House of Commons by a vote of 159 to 130 and in the Senate by a vote of 50 to 27, receiving Royal Assent on April 5, 2012.

Did this comprehensive Canadian gun law reduce the rate of gun crime in Canada between its implementation date and 2011? No.

Using official government data from the

Statistics Canada database (CANSIM Table 252-0051: Incident-based crime statistics, by detailed violations), we find that the national rate per 100,000 population for the crime of using a firearm in the commission of an offence increased linearly from 0.28 in 1998 (the earliest year for which data is available) up to 1.24 in 2004, and has remained approximately constant at this elevated level up to 2011 (the latest year for which data are available), including a peak of 1.51 in 2007. Thus, in just 7 years after bringing the gun control Bill C-68 into force, Canada's rate for the use of a firearm while committing an offence increased by a factor of 4.4 and stayed at this new higher level.

Similarly, the rate for discharging a firearm with intent increased steadily from a rate of 0.65 per 100,000 population in 1998 up to 1.81 in 2010 and 1.66 in 2011. The crime of "[w]eapons possession contrary to order" increased almost 8-fold from 0.31 per 100,000 population in 1998 to 2.33 in 2011.

We need to control for some variables, as gun control proponents may attempt to argue that crime rates in Canada were generally increasing over this timeframe; and thus, the increasing use of firearms while committing offences was just reflecting the higher overall rates of crime in the nation. Such is most definitely not the case.

The rate for all violations dropped steadily between 1998 and 2011, for a total decline of 26% during this period. Analogous declines were observed for all

Criminal Code violations including traffic (-28%) , all

Criminal Code violations excluding traffic (-29%), total violent

Criminal Code violations (-8.5%), robbery (-21%), property crime (-38%), and motor vehicle theft (-57%). Rates for homicide and attempted murder were unchanged.

By comparison, the

rates for violent crime (-32%), murder and non-negligent manslaughter (-25%), robbery (-31%), aggravated assault (-33%), property crime (-28%), and motor vehicle theft (-50%) in the United States between 1998 and 2011 were also declining rapidly, and -- in many cases -- faster than in Canada. Indeed, the rates for aggravated assault (+16%) and assault with a weapon or causing bodily harm (+18%) actually increased in Canada.

Recall how the mid-1990s gun control legislation in Canada enacted "

Criminal Code amendments providing stricter penalties for certain serious crimes where firearms are used (e.g., kidnapping, murder, etc.)"? The rate of first and second degree murder did not change in Canada between 1998 and 2011, and the rate of forcible confinement or kidnapping actually increased significantly (peaking at 128% in 2004 compared to the 1998 datum, and with an overall increase of 76% between 1998 and 2011).

These Canadian crime statistics and trends -- especially when compared against their American counterparts, where Second Amendment rights and much weaker gun control laws exist -- cannot be reconciled with the claims of gun control advocates. In fact, perhaps they agree better with the saying that "if we outlaw guns, only criminals will have guns."

There is no significant correlation between the rate of gun ownership and the homicide rate by guns among these countries.

Similarly, we see no significant correlation between the rate of gun ownership and the percentage of homicides by firearm within this group of nations.

There is no significant correlation between the rate of gun ownership and the homicide rate by guns among these countries.

Similarly, we see no significant correlation between the rate of gun ownership and the percentage of homicides by firearm within this group of nations.

Moving back to the Canadian gun control experiment, and as noted in the Royal Canadian Mounted Police 2010 report on this topic, "[i]n 1993, the Federal Government indicated its intention to proceed with additional [gun control] measures, including a universal licensing system that would apply to individuals and a universal registration system that would apply to all firearms. Senate approval and Royal Assent for Bill C-68 (An Act Respecting Firearms and Other Weapons to create the Firearms Act) were granted on December 5, 1995."

Key provisions of the Canadian law included the following:

Moving back to the Canadian gun control experiment, and as noted in the Royal Canadian Mounted Police 2010 report on this topic, "[i]n 1993, the Federal Government indicated its intention to proceed with additional [gun control] measures, including a universal licensing system that would apply to individuals and a universal registration system that would apply to all firearms. Senate approval and Royal Assent for Bill C-68 (An Act Respecting Firearms and Other Weapons to create the Firearms Act) were granted on December 5, 1995."

Key provisions of the Canadian law included the following: