By Steve Milloy ——Bio and Archives--April 19, 2011

Global Warming-Energy-Environment | CFP Comments | Reader Friendly | Subscribe | Email Us

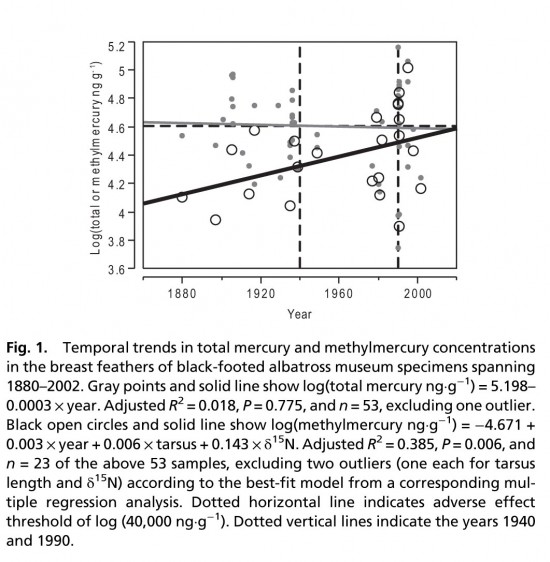

The black-footed albatross population [has since] increased from an estimated 18,000 pairs in 1923 to 61,000 pairs in 2005. As with Laysan albatrosses, the increase in the black-footed albatross population over the past 83 years probably is in response to the end of persecution at nesting colonies. Analysis of linear trends in population size showed a positive change from 1923 to 2005, no change from 1957 to 2005, and no change from 1998 to 2005.Inconveniently for the PNAS study authors, this trend coincides with the rise in mercury emissions. Like the growing polar bear population, that of the black-footed albatross is moving in the wrong direction for anti-fossil fuel worry-worters. Next, although the researchers emphasize an apparent increase in methylmercury accumulation in the albatross feathers, their data also shows that the accumulation of inorganic mercury decreased in a "strong and significant" manner. Inorganic mercury is what comes out of smokestacks and tailpipes. Methylmercury is what happens when inorganic mercury gets incorporated in the food chain. Though it's initially difficult to know what significance, if any, that observation holds, it perhaps can be explained by the creepy similarity between the PNAS study and Michael Mann's infamous and discredited hockey stick graph. Mann attempted to reconstruct historical global temperatures going back 1,000 years based on observations from just a few trees. The PNAS study authors attempt to reconstruct global mercury emissions for the period 1860 to 1940 from the feathers of what appears to be eight birds. And as can be seen from their graph (below), the more birds analyzed, the greater the variability in the measurements. So their claimed trends for mercury, if not contrived, are probably not reliable.

The PNAS authors claim that the levels of methylmercury measured in the feathers are on the order of so-called "estimated adverse thresholds."

Tracking down the studies where these "estimated adverse thresholds" were determined, I found them to be exercises in classic pre-determinism.

Although fecundability is a complex, multifactorial phenomenon, the single-minded researchers simply correlated mercury exposures with observations of adverse reproductive observations and called it a day. Wearing their mercury blinders, the researchers don't seem to care what else might be the actual cause of any of the observed reproductive shortcomings — and apparently nothing can dissuade them from their maniacal pursuit of mercury.

In one study, researchers found "no overt toxicity or reduction in growth rates" in common loon chicks fed methylmercury in excess of levels found in fish, so they're moving on to injecting methylmercury directly into loon eggs.

At some point of course, some excessive and unrealistic exposure to methylmercury will cause some sort of reproductive/developmental problem. This will enable the researchers to declare victory and to call for a ban on mercury emissions.

The latter may be tough to justify since Mother Gaia releases just about 70 percent of the mercury emitted.

The PNAS authors claim that the levels of methylmercury measured in the feathers are on the order of so-called "estimated adverse thresholds."

Tracking down the studies where these "estimated adverse thresholds" were determined, I found them to be exercises in classic pre-determinism.

Although fecundability is a complex, multifactorial phenomenon, the single-minded researchers simply correlated mercury exposures with observations of adverse reproductive observations and called it a day. Wearing their mercury blinders, the researchers don't seem to care what else might be the actual cause of any of the observed reproductive shortcomings — and apparently nothing can dissuade them from their maniacal pursuit of mercury.

In one study, researchers found "no overt toxicity or reduction in growth rates" in common loon chicks fed methylmercury in excess of levels found in fish, so they're moving on to injecting methylmercury directly into loon eggs.

At some point of course, some excessive and unrealistic exposure to methylmercury will cause some sort of reproductive/developmental problem. This will enable the researchers to declare victory and to call for a ban on mercury emissions.

The latter may be tough to justify since Mother Gaia releases just about 70 percent of the mercury emitted.

View Comments

Steve Milloy publishes JunkScience.com and GreenHellBlog.com and is the author of Green Hell: How Environmentalists Plan to Control Your Life and What You Can Do to Stop Them