By Dick Field & Ken Tellis——Bio and Archives--March 6, 2009

Canadian News, Politics | CFP Comments | Reader Friendly | Subscribe | Email Us

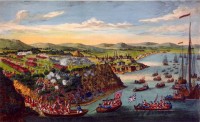

We begin the fantastic journey through the final years of the adventurous and wildly unbelievable past of the early settlement of North America by French and British people. Our story ends with the conquest of Quebec City, September 13, 1759, and the capture and surrender of Montreal in 1760. This last surrender while signifying the end of New France also heralded the beginning of the founding of the free and democratic countries of Canada (including Quebec) and the United States of America.

We begin the fantastic journey through the final years of the adventurous and wildly unbelievable past of the early settlement of North America by French and British people. Our story ends with the conquest of Quebec City, September 13, 1759, and the capture and surrender of Montreal in 1760. This last surrender while signifying the end of New France also heralded the beginning of the founding of the free and democratic countries of Canada (including Quebec) and the United States of America.

It was a dark wintry night on February 8th, 1690. The snow blew straight from the North and the Dutch villagers of Schenectady were asleep in their warm beds, little suspecting their lives were to be shattered before the sun rose in the morning. Terribly cold though it might be outside, a far greater evil was quietly descending upon them along with that frigid wind.

Little did they know that the King of France, Louis XVI, had appointed Louis de Buade, Comte de Frontenac et de Palluau, Governor of New France with a mandate to attack and destroy all British outposts in New England and New York, and to spare the lives of none of its Protestant settlers, a part of his plan to build a new Catholic empire in North America.

Under Comte Frontenac’s orders, 114 Frenchmen under the command of Le Moyne de Sainte-Helene and his deputy Daillebout de Mantet joined by 96 Roman Catholic Sault and Algonquin Indians had started out from Montreal, New France, 200 miles to the north, about the middle of January to attack Fort Orange (Albany). Wearing snowshoes and dragging sleds of supplies they had crossed the frozen St. Lawrence River, traversed Lake Champlain and in the region of where Fort Edward would later be erected, they stopped while the leaders conferred as to how they were going to attack Fort Orange. The party resumed the march to where the trail diverged, one branch leading to Albany and the other to Schenectady.

Unfortunately for the Dutch citizens of Schenectady, the leaders of the expedition, after discussion with the Chief of the Indians, Kryn, changed their target to the village of Schenectady because they felt the risks were too great to attack Fort Orange. Their feeling was that Fort Orange was more strongly fortified and might be defended by local militia and British troops.

The invaders journeyed another 7 days towards the Mohawk Valley and on February 8, 1690 arrived a few miles from a trading post near Binnekil. At 4 o’clock that afternoon there was a blizzard, followed by a nor’wester with icy winds and a snow squall. Le Moyne de Sainte-Helene and his leaders held a final council.

The council decided not to wait until the morning for the attack because the men were half frozen, fatigued and hungry. Le Moyne then ordered his Indian scouts to cross the Mohawk River to scout the area and see if the Dutch had taken any counter measures to resist a surprise attack. The scouts returned at 11 p.m. and told the commander that no one was guarding the stockade and even the gate facing the river was unguarded.

Thus on the night of February 8, 1690 while the Dutch families, snug in their well heated homes, feeling very safe from any attack because the night was extremely cold and that no enemy would be foolish enough to venture out under such terrible conditions, horror descended upon them.

The invading Frenchmen and Indians crossed the frozen Mohawk River, silently entered the stockade and surrounded the quiet houses where the Dutch families were fast asleep. Then the Sault and Algonquin Indians let out a hideous war whoop that was the signal for the start of a bloody massacre that was to last for two terrible hours.

The doors of the houses were broken down with hatchets; the settlers leapt from their beds in their nightclothes only to fall before the tomahawks; women seized their children and ran into the streets where they were shot down alike by the French and Indians. Their scalps were then taken by the screaming Indians. Neither men women nor children were spared. The snow covered streets were soon littered with the bloody bodies of the dead and dying.

The houses of the village were then set on fire and nearly eighty homes were destroyed. The winter sky was illuminated by the flames as the screaming Indians with their bloody scalps hanging by their sides danced with joy. “No pen can write, and no tongue express,” wrote Pieter Shuyler, Mayor of Albany, in a letter to Governor Bradstreet of Massachusetts, “the cruelties of women bigg with child rip’d up and ye children alive throwne into ye flames and those Dashed in Pieces against the doors and windows.”

There was little resistance except at the small blockhouse that was located in a corner of the village. Here Lieutenant Talmage and 24 of his soldiers made a stubborn stand, but the doors were forced and all but 3 of the defenders killed, the latter taken prisoner.

Another plucky fight was put up by Adam Vrooman and his family. He had a fortified house and was determined to fight to the end. Unfortunately his wife had left the top half of the Dutch door partially open and an alert Indian shot her through the opening. His daughter ran out the side door and escaped but the baby she was carrying was torn from her grasp and smashed against the door. Adam’s brisk fight brought a parley and his life was spared but his son and a Negro slave were carried into captivity.

In the attack on Schenectady 60 died or were killed by the French and Indian invaders, these included 38 men and boys, 10 women and 12 children. Some managed to escape from the stockade to seek shelter with relatives and friends some miles away. Others perished of exposure because of the bitter cold.

One of the Dutch settlers Simon Schermerhorn, though badly wounded managed to get on his horse even as the massacre was taking place and ride off through the drifting snow to Albany, New York and reached it in the early morning hours of February 9, 1690, carrying news of the attack. Eventually, a party of militia from Albany and some Mohawk warriors pursued the French and Indian invaders and killed or captured some of them almost at the environs of Montreal, New France.

The breaking of dawn brought a grim scene as the French and their Indian allies began to collect their captives, supplies and 40 pack horses to begin their long journey back to Montreal, New France. They left behind the smoldering ruins of burnt homes and blackened chimneys still smoldering, the bodies of their innocent victims with heads decapitated lay on the bloodied snow where they had been butchered and scalped by the Sault and Algonquin Indian allies of the French.

The invaders finally gathered what was left of their force, collected their 50 prisoners and headed back to Montreal, New France in the afternoon. On the way back to Montreal, 19 of the French perished and the remainder were saved from starvation by killing some of the horses and eating them. Some of the prisoners were sold on the slave market in Montreal and others were ransomed. Only one prisoner escaped and got back to the region of Schenectady.

The inhabitants of the village of Schenectady had been caught unawares because they had failed to post any sentries, and had seriously misjudged the capabilities of the French and Indians to attack in the worst of conditions. The attack was so swift and deadly that the people were unable to defend themselves or offer any meaningful resistance.

This mission by the French and Indians while tactically successful was in reality a strategic failure because the real target of Fort Orange had been scrapped. It was at best a pyrrhic victory, having served no real purpose except to display their savagery towards the Protestant settlements of the British, regardless of nationality and so arouse the anger of the New England colonies and their Iroquois allies that the cauldron of anger would take but little more to boil over.

Watch for Chapter 2 – The Deerfield Massacre 1704

Read the personal tales of the survivors.

Ken Tellis is an ex sailor who has traveled the world lived in Quebec and raised a family in the French milieu. Ken can be reached at

It was a dark wintry night on February 8th, 1690. The snow blew straight from the North and the Dutch villagers of Schenectady were asleep in their warm beds, little suspecting their lives were to be shattered before the sun rose in the morning. Terribly cold though it might be outside, a far greater evil was quietly descending upon them along with that frigid wind.

Little did they know that the King of France, Louis XVI, had appointed Louis de Buade, Comte de Frontenac et de Palluau, Governor of New France with a mandate to attack and destroy all British outposts in New England and New York, and to spare the lives of none of its Protestant settlers, a part of his plan to build a new Catholic empire in North America.

Under Comte Frontenac’s orders, 114 Frenchmen under the command of Le Moyne de Sainte-Helene and his deputy Daillebout de Mantet joined by 96 Roman Catholic Sault and Algonquin Indians had started out from Montreal, New France, 200 miles to the north, about the middle of January to attack Fort Orange (Albany). Wearing snowshoes and dragging sleds of supplies they had crossed the frozen St. Lawrence River, traversed Lake Champlain and in the region of where Fort Edward would later be erected, they stopped while the leaders conferred as to how they were going to attack Fort Orange. The party resumed the march to where the trail diverged, one branch leading to Albany and the other to Schenectady.

Unfortunately for the Dutch citizens of Schenectady, the leaders of the expedition, after discussion with the Chief of the Indians, Kryn, changed their target to the village of Schenectady because they felt the risks were too great to attack Fort Orange. Their feeling was that Fort Orange was more strongly fortified and might be defended by local militia and British troops.

The invaders journeyed another 7 days towards the Mohawk Valley and on February 8, 1690 arrived a few miles from a trading post near Binnekil. At 4 o’clock that afternoon there was a blizzard, followed by a nor’wester with icy winds and a snow squall. Le Moyne de Sainte-Helene and his leaders held a final council.

The council decided not to wait until the morning for the attack because the men were half frozen, fatigued and hungry. Le Moyne then ordered his Indian scouts to cross the Mohawk River to scout the area and see if the Dutch had taken any counter measures to resist a surprise attack. The scouts returned at 11 p.m. and told the commander that no one was guarding the stockade and even the gate facing the river was unguarded.

Thus on the night of February 8, 1690 while the Dutch families, snug in their well heated homes, feeling very safe from any attack because the night was extremely cold and that no enemy would be foolish enough to venture out under such terrible conditions, horror descended upon them.

The invading Frenchmen and Indians crossed the frozen Mohawk River, silently entered the stockade and surrounded the quiet houses where the Dutch families were fast asleep. Then the Sault and Algonquin Indians let out a hideous war whoop that was the signal for the start of a bloody massacre that was to last for two terrible hours.

The doors of the houses were broken down with hatchets; the settlers leapt from their beds in their nightclothes only to fall before the tomahawks; women seized their children and ran into the streets where they were shot down alike by the French and Indians. Their scalps were then taken by the screaming Indians. Neither men women nor children were spared. The snow covered streets were soon littered with the bloody bodies of the dead and dying.

The houses of the village were then set on fire and nearly eighty homes were destroyed. The winter sky was illuminated by the flames as the screaming Indians with their bloody scalps hanging by their sides danced with joy. “No pen can write, and no tongue express,” wrote Pieter Shuyler, Mayor of Albany, in a letter to Governor Bradstreet of Massachusetts, “the cruelties of women bigg with child rip’d up and ye children alive throwne into ye flames and those Dashed in Pieces against the doors and windows.”

There was little resistance except at the small blockhouse that was located in a corner of the village. Here Lieutenant Talmage and 24 of his soldiers made a stubborn stand, but the doors were forced and all but 3 of the defenders killed, the latter taken prisoner.

Another plucky fight was put up by Adam Vrooman and his family. He had a fortified house and was determined to fight to the end. Unfortunately his wife had left the top half of the Dutch door partially open and an alert Indian shot her through the opening. His daughter ran out the side door and escaped but the baby she was carrying was torn from her grasp and smashed against the door. Adam’s brisk fight brought a parley and his life was spared but his son and a Negro slave were carried into captivity.

In the attack on Schenectady 60 died or were killed by the French and Indian invaders, these included 38 men and boys, 10 women and 12 children. Some managed to escape from the stockade to seek shelter with relatives and friends some miles away. Others perished of exposure because of the bitter cold.

One of the Dutch settlers Simon Schermerhorn, though badly wounded managed to get on his horse even as the massacre was taking place and ride off through the drifting snow to Albany, New York and reached it in the early morning hours of February 9, 1690, carrying news of the attack. Eventually, a party of militia from Albany and some Mohawk warriors pursued the French and Indian invaders and killed or captured some of them almost at the environs of Montreal, New France.

The breaking of dawn brought a grim scene as the French and their Indian allies began to collect their captives, supplies and 40 pack horses to begin their long journey back to Montreal, New France. They left behind the smoldering ruins of burnt homes and blackened chimneys still smoldering, the bodies of their innocent victims with heads decapitated lay on the bloodied snow where they had been butchered and scalped by the Sault and Algonquin Indian allies of the French.

The invaders finally gathered what was left of their force, collected their 50 prisoners and headed back to Montreal, New France in the afternoon. On the way back to Montreal, 19 of the French perished and the remainder were saved from starvation by killing some of the horses and eating them. Some of the prisoners were sold on the slave market in Montreal and others were ransomed. Only one prisoner escaped and got back to the region of Schenectady.

The inhabitants of the village of Schenectady had been caught unawares because they had failed to post any sentries, and had seriously misjudged the capabilities of the French and Indians to attack in the worst of conditions. The attack was so swift and deadly that the people were unable to defend themselves or offer any meaningful resistance.

This mission by the French and Indians while tactically successful was in reality a strategic failure because the real target of Fort Orange had been scrapped. It was at best a pyrrhic victory, having served no real purpose except to display their savagery towards the Protestant settlements of the British, regardless of nationality and so arouse the anger of the New England colonies and their Iroquois allies that the cauldron of anger would take but little more to boil over.

Watch for Chapter 2 – The Deerfield Massacre 1704

Read the personal tales of the survivors.

Ken Tellis is an ex sailor who has traveled the world lived in Quebec and raised a family in the French milieu. Ken can be reached at View Comments

Dick Field, editor of Blanco’s Blog, is the former editor of the Voice of Canadian Committees and the Montgomery Tavern Society, Dick Field is a World War II veteran, who served in combat with the Royal Canadian Artillery, Second Division, 4th Field Regiment in Belgium, Holland and Germany as a 19-year-old gunner and forward observation signaller working with the infantry. Field also spent six months in the occupation army in Northern Germany and after the war became a commissioned officer in the Armoured Corps, spending a further six years in the Reserves.