By Dr. Bruce Smith ——Bio and Archives--November 5, 2023

HeartlandLifestyles | CFP Comments | Reader Friendly | Subscribe | Email Us

Every year the approach of November 10 still gives me chills and a deep sense of horror. It was on that date in 1975 that the sturdy Edmund Fitzgerald disappeared beneath the always icy waters of mighty Lake Superior, the victim of a deep low pressure system that developed in the southern plains before racing up across Lake Superior into Ontario and up to James Bay. After a terrifying and sleepless night on the raging lake, buffeted by waves of 25 feet and more, the ship went down in total darkness without sending a distress signal. All 29 officers and crew were lost. The 729-foot ship broke in two and lies on the bottom of the cold lake to this day. It was only 17 more miles to the slightly more protected waters of Whitefish Bay.

The memory of that day sobers me every year. I was teaching high school history classes at my first job after graduating from Indiana University the previous May. It came over the car radio as I drove home in the afternoon. I did some research and began to understand the lakes I had always taken for granted.

The Great Lakes are one of the most remarkable geographical features in the world. Now that they are navigable by ocean-going vessels from the Atlantic all the way to the western end of Lake Superior, they present a shipping opportunity unequalled throughout the world. Upon their waters major vessels may travel more than 1500 miles into the center of a large continent. Such a thing is simply not possible anywhere else. Just as I always remark about what a big continent we are blessed to live on, seeing any part of any of the five great lakes reminds me what a treasure they are.

I’ve seen all five of the great lakes plus Lake St. Clair and Georgian Bay. I’ve been out of sight of land on the ferry across Lake Michigan. All of the lakes are impressive in their own way. I’ve been to lake cities like Gary and Chicago and Milwaukee and Escanaba, Detroit, Buffalo, Hamilton, Port Huron, and Cleveland.

Lake Superior is in a class of its own. I’ve been to the shores of Lake Superior many times. I’ve been to Duluth, Houghton, Marquette, and to Pictured Rocks. One time I put a hand in the lake, and even in the summer time I learned that it’s cold water. I’ve been to Sault Ste. Marie and seen the locks. On many other occasions I’ve crossed the Mackinac Bridge both directions. It spans the waters between Lake Michigan and Lake Huron. I’ve seen ore boats on the lakes many times. In the early morning hours of November 10 that year, the ‘good ship and true’ was carrying 26,000 tons of taconite. Taconite is a semi-refined iron ore that trains and ships take to mills for smelting into iron and steel products. Not all of the taconite moves aboard ships. At the railroad crossing in Rock, Michigan and many other places in the Upper Peninsula there are always handfuls of taconite pellets to be had for a souvenir. They bounce off the railroad hopper cars when they come to the crossing there on the west side of Highway M35.

Support Canada Free Press

I felt the lake’s influence and moderation during several winters in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan. Like all large bodies of water, Lake Superior has a moderating effect on the land nearby. In the winter time, the lake keeps the surrounding leeward areas of Michigan, Wisconsin, Minnesota, and Ontario a little warmer than it would be were the lake not there.

In the summer time, the same lake keeps nearby lands a little cooler. It’s because water absorbs and gives off heat more slowly than the surrounding land. Where prevailing winds pass over bodies of water there are often ‘snow belts’ in the leeward areas in the winter. The Houghton Peninsula is a good example of this effect. The town of Houghton, located better than half way up the peninsula, averages better than 200 inches of snow each year. Big lakes make their presence known in many ways. Ask anyone in Buffalo, Charlevoix, Watertown, or South Bend.

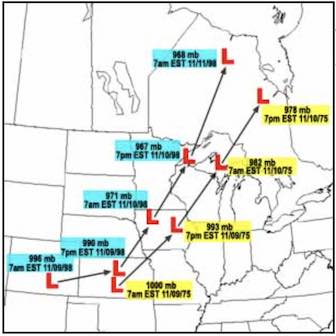

Each year the memory of that terrible storm has me watching the weather patterns in the first ten days of November. It’s not unusual to see just such a storm follow a similar path from the plains up across the upper Midwest and over the Great Lakes into Ontario. It is unusual, however, to see a storm as severe as the one in 1975. On the linked map, we can see the tracks of the 1975 and 1998 storms.

A Witch of November storm will rattle the windows and even make sheep and chickens glad that they’re snug in sturdy henhouses and barns with plenty of feed in barrels and straw and hay stacked nearby to see them through. In hard winter areas near the lakes the folks know how to get ready for the next one. Rural roads in the Upper Peninsula often aren’t plowed after a big snow. They’re groomed more like ski trails to make them level, but it snows so often that having cleared roads waits until spring in many areas. Four wheel drive trucks and snowmobiles are everywhere. Those who don’t have them stay home or leave for the winter. When there’s a storm on the way, grocery stores and carry outs do a raging business until just before it hits. Then the streets and country roads are quiet for a few days until the winds die down. Generators and snow blowers can be heard here and there. Even the herds of deer bed down in cedar swamps for the duration.

Great Lakes winters remind us of the last ice age, which, come to think of it, wasn’t that long ago.

Of course, it was Gordon Lightfoot’s song that brought the events of that November to everyone, and it still does. It has a sea shanty rhythm to it, and the lyrics are understandable. He imagines what the crew might have said to each other as they moved eastward on the lake in the storm with the wind behind them, and how conditions deteriorated when they turned south. After the turn the waves were striking the starboard side. Later on, in Detroit, the bell at the Maritime Sailors’ Cathedral tolled 29 times. It still does every year on November 10.

All of these places and memories are reminders that we depend on many people we never see to farm and mine and manufacture the goods we use and consume. It’s a brilliant example of spontaneous order. We don’t tell anyone to mine iron ore or ship it, we don’t run lumber companies or farms or steel mills. We simply go to retailers and purchase what we need. In this month of Thanksgiving, we can give thanks that there are miners and sailors and steelworkers and factory workers who provide for us without knowing who we are.

View Comments

Dr. Bruce Smith (Inkwell, Hearth and Plow) is a retired professor of history and a lifelong observer of politics and world events. He holds degrees from Indiana University and the University of Notre Dame. In addition to writing, he works as a caretaker and handyman. His non-fiction book The War Comes to Plum Street, about daily life in the 1930s and during World War II, may be ordered from Indiana University Press.