The Transformative Power of Hate

Panthers

Racial prejudice is ugly. I never knew how ugly until I was on the receiving end.

“Cornell” was a black kid from the projects on the South Side of Chicago. He was a neatly dressed, diminutive young man, with a round, open face and a smile that could light up a room. He was the kind of guy you instantly liked. And we became fast friends my sophomore year in college. I was a small town boy from rural southern Iowa and he was a big city boy from Chicago. Neither of us had really ever had a friend like the other. He did not run around with many white kids in school. Other than one family in my hometown—who were nice folks and well respected in the community—I did not know many black people.

We often went to the student union and played pool, or ate dinner in the dorms and generally hung out together for almost a year until. I enjoyed his company. He was a cute kid, intelligent, and fun to be around. He was one of my best friends.

During the late sixties and early seventies, The University of Iowa was a melting pot of many races, nationalities, religions, ethnic groups and philosophies. It was part of the attraction of the place. It is where small town Iowa kids met people from diverse cultures and backgrounds; and where people from other cultures met Midwesterners—some of the friendliest, most hospitable people in the world. Iowa was a tolerant place and the university was special. It was not a place associated with hate groups. There were no Skinheads or black separatist groups or other such groups on campus. Iowa was, generally, mellow. Everyone largely got along and benefited from the association with others of different backgrounds. It was part of the attraction of the place, and one of the main reasons I attended the school.

But, during Vietnam, the school experienced an occasional protest, riot, and even one pitched battle in the streets between war protestors and police which resulted in the tear gassing of a dorm and a few burned buildings. Some said that Iowa stood second only to Berkeley and Madison when it came to anti-war protests. Like society in general, the University of Iowa was a place of social and political ferment. Some of the more radical elements on campus such as the SDS and Weathermen—of which there were a few—preached hatred of the system, overthrow of capitalism, and declared war on The Man. After Kent State, we had our share of riots in the streets—some of which were ugly. As an Army ROTC student, I experienced the wrath of the protestors first hand on more than one occasion. It was a strange, interesting, introspective and even tumultuous time for the campus as with much of society in general. Some of the voices were strident, even ugly. Students with malleable minds could be influenced, in bad ways.

Cornell was a shy, quiet kid--studious and, most of the time, reserved. Other than me, he seemed to have few friends on campus. I valued his friendship and I believed it worked both ways. There was no indication to the contrary.

One day everything changed. After class, I went to his room and knocked on the door to see if he wanted to hang out that night after studying. For reasons I could not divine, he was uncharacteristically aloof and even unfriendly. Did he want to hang out? I asked him. “Naw, man,” he said, dismissively, “I got a thing tonight. Maybe some other time.” Then he shut the door. I retreated to my room. Perhaps he was having a bad day.

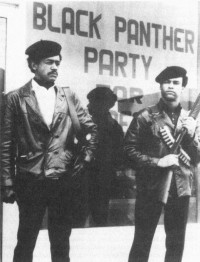

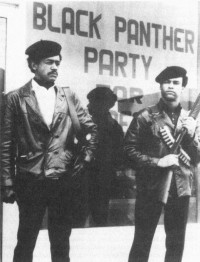

I did not know that the Black Panther Party was holding a rally for black students that very evening. This black nationalist hate group that preached Maoism, violence, hatred of the white race, and overthrow of the government, had come to campus to recruit new members. Their founders were associated with murders of police officers and civilians alike, violence against the government, robberies, and bombings. I could no more imagine my friend going to a Panther rally that I could envision myself attending a Skinhead convention. Unfortunately, this rally was the “thing” that Cornell had going that night. That he would go was unthinkable.

The next day, after class I met Cornell in the hallway. Something had changed. He was sullen and morose. Gone was the radiant smile. The look he gave me sent chills down my spine. This was not the Cornell I knew, but a hostile, scowling person, wearing a black leather jacket and looking like he could spit. I was almost afraid to approach him.

“Do you want to hang out?” I asked, timidly.

“No, man,” he replied, curtly.

“What’s up?” I asked.

“You’re just like all the rest of those Honky Mother-*******!” he replied, as he walked off.

I stood there in the hallway, nonplussed, and reeling from the imaginary knife in my gut.

Sadly, we never hung out again. He became hateful, reclusive, and avoided the guys on the floor. What happened the night before, I do not know, but the transformation was startling. Gone was the valued friend whose company I enjoyed, and with whom I had never had a cross word. In his place stood a bigot and a stranger I never knew. The change was ugly and shocking. Whatever poison they fed him was powerful and fast acting. Had I been so naïve? Was there a racist beneath a veneer of civility and friendliness that I had not seen? Whatever demons had lurked beneath the surface, the Panthers were able to draw out. They turned a very nice young man into a hate-filled racist.

Sadly, we never spoke again. To him, I was a just a white-skinned devil like all the rest. He no longer wanted my company. I was no longer his friend, his companion, confidante or pool playing buddy. I was simply white and, therefore, the Enemy. My father once said that there is no bad experience--only experience. And it happens either for our benefit or guidance. If there was anything to be gained from this episode it was this: I learned how I never want to treat others. And how demeaning it is to judge another by their skin tones.

In time the Panthers became largely irrelevant (if they ever were relevant) and their influence waned. They became merely an evil footnote in the history of race relations in America. They were hoist by their own petard. Ultimately the very violence they preached was their undoing. Many of their founders were jailed, killed during shootouts, or otherwise died violently. Some, like Eldridge Cleaver, saw the light, turned to religion, renounced violence, and tried to become productive members of society. But they were the exception. When it came to hate mongering, they were good at what they did. And the damage they did to race relations in this country was incalculable. To this day, I curse their memory, these Panthers. It was not so much the racial insult, or the fact that I became, briefly, the object of prejudice. It was the look in his eyes that I will remember--the transformative power of hate. The worst part was, it cost me a friend.

William Kevin Stoos -- Bio and

Archives |

Comments

Copyright © 2020 William Kevin Stoos

William Kevin Stoos (aka Hugh Betcha) is a writer, book reviewer, and attorney, whose feature and cover articles have appeared in the Liguorian, Carmelite Digest, Catholic Digest, Catholic Medical Association Ethics Journal, Nature Conservancy Magazine, Liberty Magazine, Social Justice Review, Wall Street Journal Online and other secular and religious publications. He is a regular contributing author for The Bread of Life Magazine in Canada. His review of Shadow World, by COL. Robert Chandler, propelled that book to best seller status. His book, The Woodcarver (]And Other Stories of Faith and Inspiration) © 2009, William Kevin Stoos (Strategic Publishing Company)—a collection of feature and cover stories on matters of faith—was released in July of 2009. It can be purchased though many internet booksellers including Amazon, Tower, Barnes and Noble and others. Royalties from his writings go to support the Carmelites. He resides in Wynstone, South Dakota.

“His newest book, The Wind and the Spirit (Stories of Faith and Inspiration)” was released in 2011 with all the author’s royalties go to support the Carmelite sisters.”

Racial prejudice is ugly. I never knew how ugly until I was on the receiving end.

“Cornell” was a black kid from the projects on the South Side of Chicago. He was a neatly dressed, diminutive young man, with a round, open face and a smile that could light up a room. He was the kind of guy you instantly liked. And we became fast friends my sophomore year in college. I was a small town boy from rural southern Iowa and he was a big city boy from Chicago. Neither of us had really ever had a friend like the other. He did not run around with many white kids in school. Other than one family in my hometown—who were nice folks and well respected in the community—I did not know many black people.

Racial prejudice is ugly. I never knew how ugly until I was on the receiving end.

“Cornell” was a black kid from the projects on the South Side of Chicago. He was a neatly dressed, diminutive young man, with a round, open face and a smile that could light up a room. He was the kind of guy you instantly liked. And we became fast friends my sophomore year in college. I was a small town boy from rural southern Iowa and he was a big city boy from Chicago. Neither of us had really ever had a friend like the other. He did not run around with many white kids in school. Other than one family in my hometown—who were nice folks and well respected in the community—I did not know many black people.