By Dr. Bruce Smith ——Bio and Archives--December 9, 2023

HeartlandLifestyles | CFP Comments | Reader Friendly | Subscribe | Email Us

Growing up the first few years next to the grandparents’ farm in Henry County, Indiana, it was the most natural thing in the world to pay attention to the weather. I remember days with puffy cumulus clouds and chilly breezes after a storm. There was a spell of several days of rain one spring before I started school. There was a memorable blizzard in ’61 during the basketball tournament.

When we visited any family relatives, weather was always the first topic of conversation. There were crops to plant in the spring, but the ground couldn’t be too wet or too cold. When it was time to cut wheat, heavy rain or wind could lodge the grain, making harvest difficult.

The chanciest crop was hay, of course. It needed rain to grow, but almost any rain after it had been mowed portended disaster. In those days before haybines and tedders became common, it took three full days of ideal weather to dry it down enough to bale.

Midwest summers are humid, so predicting three straight days of dry heat was not an easy thing to do. If fine cattle depended on the crucial first and second cutting, it was essential to be able to predict the unpredictable weather. The ground needed to be fairly dry to run the cultivators.

In the fall, corn needed to dry on the stalk, then be picked and later shelled when the ground was either dry or frozen. My grandparents also had a large garden, so weather was a consideration every day of the year.

There were minimalist weather forecasts in the daily papers, and more on the radio if there were a farm show like one that could be heard at 1190 on the AM dial, WOWO in Ft. Wayne. Beyond these and a glance at the almanac, weather forecasting was a survival skill developed on the farm.

Without a barometer, my grandfather made his observations based on patterns, and hoped they held steady. Wind direction was important, so the weathervane on the barn was much more than just an ornament. Clouds were important. The time of year was important.

Some weather phenomena were common in March, others in June. Even in school we learned that April showers bring May flowers. The expected date of the last frost was etched in every farmer’s memory. In Henry County, that frost date is April 19. April is the month to plant corn, but frost will usually kill sprouted corn and cold, wet ground will cause the seed to rot. Plant it too early and invite disaster. Plant it too late and suffer yield losses.

Before I was aware of any of it there was a photo taken of me standing on a bale of alfalfa hay with my grandfather standing beside me down in the south hayfield by the big bur oak. It looks like I’m about three.

Support Canada Free Press

He’s mighty proud of that hay, and the sleek black cattle enjoyed it the following January when they were snug in the snowy barn. My brothers and I come from real hog, cattle, and poultry farm people. The photo brings tears to my eyes today.

With a child’s natural curiosity, weather and about everything else around the farm was plenty interesting. It was also important to the people in my world. As it turned out, it was important to everyone else in the world, too. I paid more and more attention to it. After all, The Cat in the Hat is all about the mayhem that may occur when we’re stuck inside on a rainy day. Noticing and observing the weather came first, but the beginnings of understanding took many years.

The American Midwest is in the Temperate Zone with prevailing westerly winds and a continental climate. That means there are hot, humid summers and cold, dry winters. Both spring and fall last long enough to be memorable. Henry County is near 40 degrees north latitude, neither northern nor southern. It’s a battleground between cold Canadian air masses and warm, humid air from the southern plains and the Gulf of Mexico. The Coriolis effect means the westerlies move low pressure systems across the Heartland from approximately southwest to northeast. The warm, humid air comes from south of us and the cold, dry air comes down from Canada. When they meet it can get very scary.

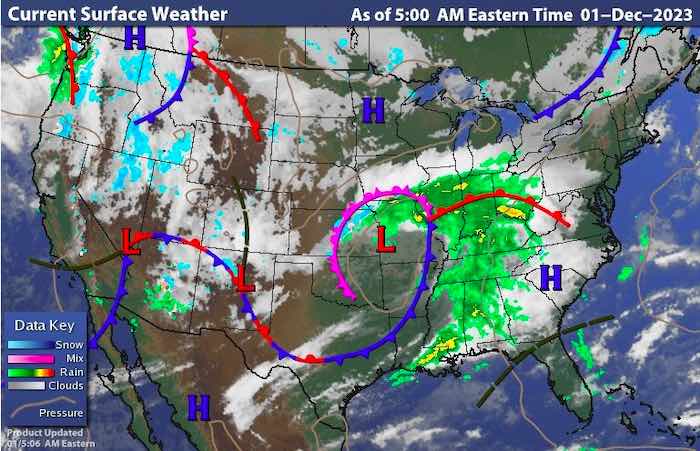

When the low pressure systems form and move across the North American landmass, they follow a pattern. Learning the pattern is the key to planting corn, making hay, and anticipating both storms and fair weather. In the Northern Hemisphere winds blow toward the centers of lows from all directions in a counterclockwise manner. Here in the Heartland when a low pressure system approaches from the west, the wind will come in from the east, southeast, south, or southwest. After the low pressure center passes, the wind will swing around to the west, northwest, or north. Frontal boundaries form around the lows and along the edges of the air masses. Clouds and precipitation occur along the boundaries. With today’s Doppler radar, we can see these patterns as comma-shaped. Here is a screen shot from about a year ago showing a classic low pressure comma.

To the left (west) of the low pressure center is the colder air coming down from Canada and the northwest. Some light snow shows blue. To the right (east) of the low is the warmer air and most of the rain in greens and yellows.

If I stand in the middle of the National Road facing east anywhere in Indiana as a low pressure system approaches from the west, wind will come in from the northeast, east, southeast, or south, depending on whether the low is further south in Missouri or further north in Iowa. The barometer will be falling and there is a growing chance of rain. When the boundary between the warm air in front and the cooler air to the west passes, the wind will swing around to the west, northwest, or north. Now the barometer will be rising. The air will be cooler and dryer as the chance of precipitation declines.

When my grandfather went outside each morning, the first thing to note was the wind direction. North or northwest wind meant that a cold front had passed and the day would be chilly or colder. Rain or snow was likely over. Wind out of the east meant that a low was coming from somewhere in Missouri, bringing rain in a day or two. Stronger winds mean a more powerful low pressure center. In the summertime, south winds often brought thunderstorms. He knew his patterns well enough to predict when a storm would pass. A drop in temperatures often brings in a few days of dry weather with low cumulus clouds. That cool morning in June might be a good time to mow alfalfa, once the dew dries off.

To summarize, lows bring a falling barometer, increasing winds, precipitation, and storms, often in comma-shaped systems as they pass west to east.

Highs bring a rising barometer, diminishing winds, dryer, cooler air, and fair weather. High pressure builds in behind the comma as it moves off to the east and northeast.

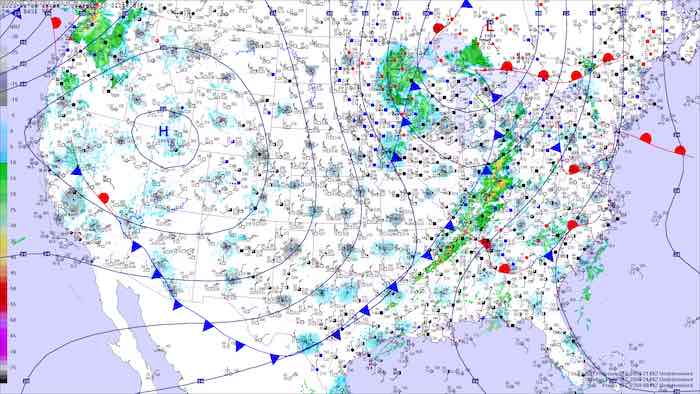

Mixed surface analysis maps will give frontal boundaries and radar precipitation. Sometimes these sites will offer forecast surface maps to give an idea of the weather to come in the next two or three days. Whether it’s the weather for a picnic, reunion, berry picking, or time on the slopes, there’s likely to be some kind of weather when everybody arrives. Get ahead of them by consulting the barometer and the old weather vane. You don’t have to tell them you looked at the latest maps and radar.

Here is the mixed surface map for December 9, 2023. There’s a big ol’ comma out there!

View Comments

Dr. Bruce Smith (Inkwell, Hearth and Plow) is a retired professor of history and a lifelong observer of politics and world events. He holds degrees from Indiana University and the University of Notre Dame. In addition to writing, he works as a caretaker and handyman. His non-fiction book The War Comes to Plum Street, about daily life in the 1930s and during World War II, may be ordered from Indiana University Press.