By Kelly O'Connell ——Bio and Archives--June 13, 2010

Cover Story | CFP Comments | Reader Friendly | Subscribe | Email Us

Outlined in this essay is a brief description of how the biblical concept of covenant became the foundation for America's Constitution. While this history is now an almost unknown, sub rosa embarrassment to modern eyes, yet the development of American political theory was once highly regarded by most of the world. Seminal colonial American historian Donald Lutz, in his Origin of American Constitutionalism, explains the importance of the Bible's covenant concept to our Pilgrim and Puritan forbears.

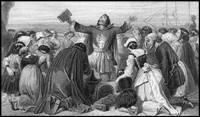

Outlined in this essay is a brief description of how the biblical concept of covenant became the foundation for America's Constitution. While this history is now an almost unknown, sub rosa embarrassment to modern eyes, yet the development of American political theory was once highly regarded by most of the world. Seminal colonial American historian Donald Lutz, in his Origin of American Constitutionalism, explains the importance of the Bible's covenant concept to our Pilgrim and Puritan forbears.A. Early American Community Foundation: Covenant of the Charles-Boston Church The following is a typical founding colonial community charter: The Covenant of the Charles-Boston Church (1630) In the Name of our Lord Jesus Christ, and in Obedience to his holy Will and Divine Ordinance, We whose Names are here under written, being by his most wise and good providence brought together into this part of America in the Bay of Massachusetts, and desirous to unite ourselves into one Congregation or Church under the Lord Jesus Christ our Head, in such sort as becometh all those whom he hath redeemed, and sanctified to himself, DO hereby solemnly and religiously (as in his most holy Presence) promise and bind ourselves, to walk in all our ways according to the Rule of the Gospel, and in all sincere Conformity to his holy Ordinances, and in mutual Love and Respect each to other, so near as God shall give us Grace. John Winthrop | Thomas Dudley | Isaac Johnson | John Wilson | &c | &cAccording to Lutz, records show that typically the first thing these newly arrived Calvinist believers did was to establish a formal relationship with one another centered upon the church which also conferred community privileges. This is understandable given the amount of persecution they received back in England, via Bishop Laud's Starr Chamber, etc. Lutz identifies five foundational elements in the Charles-Boston Church covenant doctrine, which were typical of these kinds of documents, being: 1) It is sworn before God; 2) It describes the reason the document was necessary; 3) It creates “a people” – being the undersigned; 4) It creates a church; 5) It describes what kind of people the undersigned design to become (a people who follow God's Gospel and ordinances, etc). B. Early American Political Compact: The Mayflower Compact

Agreement Between the Settlers at New Plymouth (1620) IN THE NAME OF GOD, AMEN. We, whose names are underwritten, the Loyal Subjects of our dread Sovereign Lord King James, by the Grace of God, of Great Britain, France, and Ireland, King, Defender of the Faith, &c. Having undertaken for the Glory of God, and Advancement of the Christian Faith, and the Honour of our King and Country, a Voyage to plant the first Colony in the northern Parts of Virginia; Do by these Presents, solemnly and mutually, in the Presence of God and one another, covenant and combine ourselves together into a civil Body Politick, for our better Ordering and Preservation, and Furtherance of the Ends aforesaid: And by Virtue hereof do enact, constitute, and frame, such just and equal Laws, Ordinances, Acts, Constitutions, and Officers, from time to time, as shall be thought most meet and convenient for the general Good of the Colony; unto which we promise all due Submission and Obedience. IN WITNESS whereof we have hereunto subscribed our names at Cape-Cod the eleventh of November, in the Reign of our Sovereign Lord King James, of England, France, and Ireland, the eighteenth, and of Scotland the fifty-fourth, Anno Domini; 1620.One can see here the almost identical formula between the Mayflower Compact and Charles-Boston Church covenant. But instead of creating a church, it establishes a Body Politick. C. Pilgrim Code of Law (1636) The Pilgrim Code of Law of the Plymouth Colony was officially based upon the Mayflower Compact as a legal precedent, and also the royal charter, claims Lutz. The document asserts all former covenants and compacts, turning it into a larger covenant. It then makes an extraordinarily important claim – the colonists assert all rights due Englishmen, which is now known as the “Plymouth Agreement.” This then establishes a foundation for the legal resistance to England when the Founders claim their rights are being trampled. But the Pilgrim Code of Law adds a description of the institutions by which the people will assert their rights and also establish a government. In doing this, the Code becomes the first American constitution. Of course this document influenced the US Constitution we still use today.

View Comments

Kelly O’Connell is an author and attorney. He was born on the West Coast, raised in Las Vegas, and matriculated from the University of Oregon. After laboring for the Reformed Church in Galway, Ireland, he returned to America and attended law school in Virginia, where he earned a JD and a Master’s degree in Government. He spent a stint working as a researcher and writer of academic articles at a Miami law school, focusing on ancient law and society. He has also been employed as a university Speech & Debate professor. He then returned West and worked as an assistant district attorney. Kelly is now is a private practitioner with a small law practice in New Mexico.